Workers maintain a section of the Central Asia-China Gas Pipeline in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Photo: VCG

Oscar, a Kazak national, was patrolling like any other day along the Central Asia-China Gas Pipeline in Kazakhstan. A vice manager for the security department in AGP (Asia Gas Pipeline LLP), a joint natural gas pipeline company between China and Kazakhstan, he has worked there for the past eight years.

Entering winter in late-December, the demand for natural gas had been increasing dramatically in China as millions of households have recently began transitioning from coal to gas to heat for heating their homes following the government's push for a cleaner environment.

In Kazakhstan, several hundred security staff with AGP patrol 1,300 kilometers along the pipes day and night. They are armed with guns, batons, and satellite phones.

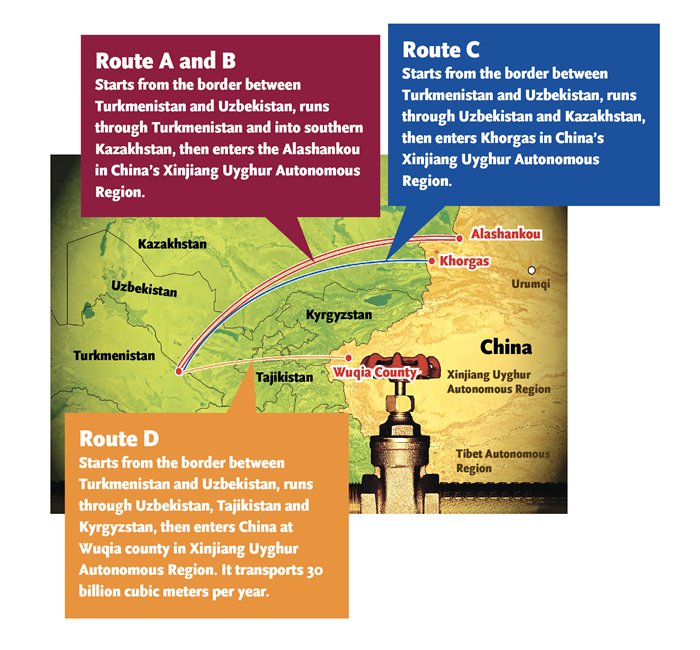

The Central Asia-China Gas Pipeline, which transmits natural gas all the way to China's east coast, is 10,000 kilometers in length. About 2,000 kilometers of pipe are located outside of China, namely in Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan.

Unlike in African countries or Uzbekistan, where army soldiers shoulder the duty of guarding gas pipelines, in Kazakhstan the pipeline is guarded by private security companies, as written into the country's law.

Kazakhstan is located at a high latitude and has a climate similar to China's Northwest and Northeast regions. Every winter the rural roads become frozen. In the wilderness, the only way to call for help is through satellite phones, as mobile phones receive no signal or service.

When Oscar's pickup once got stuck in mud, he had to call two other patrol cars, but those two cars also got stuck. In the end they had to contact a staff member living in a village 50 kilometers away, who borrowed a big truck to rescue the three vehicles.

It was just another day for Oscar and other pipeline guards, who stood outside in piercing wind and sub-zero snow for nine straight hours before their patrol cars were rescued. Villagers nearby all have sons or friends working for the security companies that guard the pipeline.

Guards and other personnel participate in an inauguration ceremony at a gas production facility in 2009 for a new pipeline running from Turkmenistan through the neighboring Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan into Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. Photo: VCG

Plurilateral agreements

PetroChina provides 30,000 jobs to Kazak locals. And as more and more locals are employed, gas companies across Central Asia are sending many of them to China to learn the Chinese language and culture.

"We have transported many talents specializing in oil. Some [local companies] even try to pirate them from us with higher salaries," said Chen Zixin, who works for a pipeline company under Petro China in Uzbekistan.

Along the 1,300-kilometer Kazakhstan-portion of the Central Asia-China Gas Pipeline, dozens of security posts are allocated. Mostly located in the uninhabited wild, these pipes are prone to erosion, natural disasters (including earthquakes and landslides), accidents involving pipe fractures or oil and gas leaks, and even human-caused damage such as theft and illegal drilling.

Oil and gas pipes are under continuous high pressure and temperatures, which makes them highly flammable and combustible. If an oil spill or gas leak occurs, it will not only halt transmission but also severely pollute the environment, threatening the local ecosystem and nearby villagers' lives.

To ensure the safety of its pipelines, AGP has strict requirements about the security companies it employs. First, the company must have experience in the protection and maintaining of gas and oil pipelines. Second, the company must be qualified, certified and authorized to use guns and ammunition - and not afraid to use them when threats appear.

Southern Weekly learned that every year, AGP, the security company and the Kazak government and its police sign plurilateral agreements (multinational legal contracts) to jointly prevent threats, emergencies and disasters that could possibly occur along the Central Asia-China Gas Pipeline.

Oscar told Southern Weekly that no major safety problems have occurred along the pipeline between China and Kazakhstan since 2008. Occasionally, children from nearby villages steal parts such as solar cells, but that is nothing he and his team can't handle.

The local government also publicizes and educates locals about how they too can protect the pipeline, explaining to them the vital importance of the Central Asia-China Gas Pipeline.

Graphics: VCG/GT

Extreme conditions

China's gas consumption in 2017 was estimated to have exceeded 230 billion cubic meters, up 17 percent from a year earlier, according to statistics released by China's National Development and Reform Commission.

Thus, how to guarantee the pipeline's safety and security has become an increasingly prominent issue, as terrorist attacks are veritable ticking time bombs for guards working the Kazakhstan segment of the Central Asia-China Gas Pipeline.

Oscar said that they often negotiate with Kazakhstan's national security council in response to possible terrorist attacks. "Our purpose is to make preparations," he said.

Many Chinese are working as guards in Central Asia to further safeguard the pipeline. In Uzbekistan, these guards are also tormented by the extreme weather, from sub-zero winters to scalding summers.

"It's extremely hot here in the summer; temperatures reach over 50 C," said Zuo Dong, chief of a station which pumps pressure for the pipeline. The station is operated by a joint venture between China National Petroleum Corporation and its Uzbekistan partners.

Zuo also warned the Southern Weekly reporter of the threat of tarantulas, which are about the size of a human hand and venomous.

Gazli, a town known for one of the largest gas fields in Central Asia, is surrounded by the Gobi Desert, which suffers long, hot summers and brief but freezing winters. There, the pipeline guards shovel snow or sand for exercise depending on the season.

Zuo recalled that once, in July of 2016, a compressor set suddenly stopped operating owing to the 40 C temperature that day. Employees fortunately solved the problem within two hours. Zuo's station is the first stop for natural gas transported from Uzbekistan to China, and equipment failure could lead to a complete halt in gas.

"Delaying for even a short while would have affected the amount of gas transported through the pipe," Zuo said, adding that due to current low winter temperatures in Uzbekistan, the station has shortened its inspection gaps from every four hours to every two hours to prevent pipe cracking, swelling or blocking.

Sacrificing for their country

Earthquakes are another old friend for station employees. Ye Erbo, deputy chief of the Gazli Compressor Station (GCS), recalled his first earthquake experience in Uzbekistan.

"I stormed out of my room after someone shouted 'earthquake,' but they all laughed when I was outside," Ye said, explaining that he still had on a whitening facial mask, because he planned to return to China the next day to see his girlfriend.

According to China's Ministry of Commerce, Uzbekistan's capital city, Tashkent, experiences around 20 earthquakes every year at a scale of two to four magnitude. "We experienced two earthquakes in April of 2016," Ye was quoted as saying.

Ye graduated from Beihang University and arrived in Gazli in January of 2012. He said that it was drastically different from what he initially envisioned. "There was nothing here but bumpy, muddy roads," he laughed.

None of Ye's family members understand his job; even his girlfriend refuses to tell her own family what he does for a living. "I did not expect myself to stay for such a long time. Probably people cannot leave a place when they get used to it and fall in love with it," said Ye.

Presently there are 15 employees aged between 30 to 40 years-old working at the WKC2 and GCS stations. Lü Ziwen, the first chief of WKC2 station, joined in 2012. He shed tears when speaking about his family back in China.

"My newborn son has not seen me for a year and a half. He called me 'uncle' the last time I came back home," Lü wept.

"We left wives and children at home to ensure that our countrymen thousands of miles away can use clean natural gas," said Lü, "It is where our courage comes from."