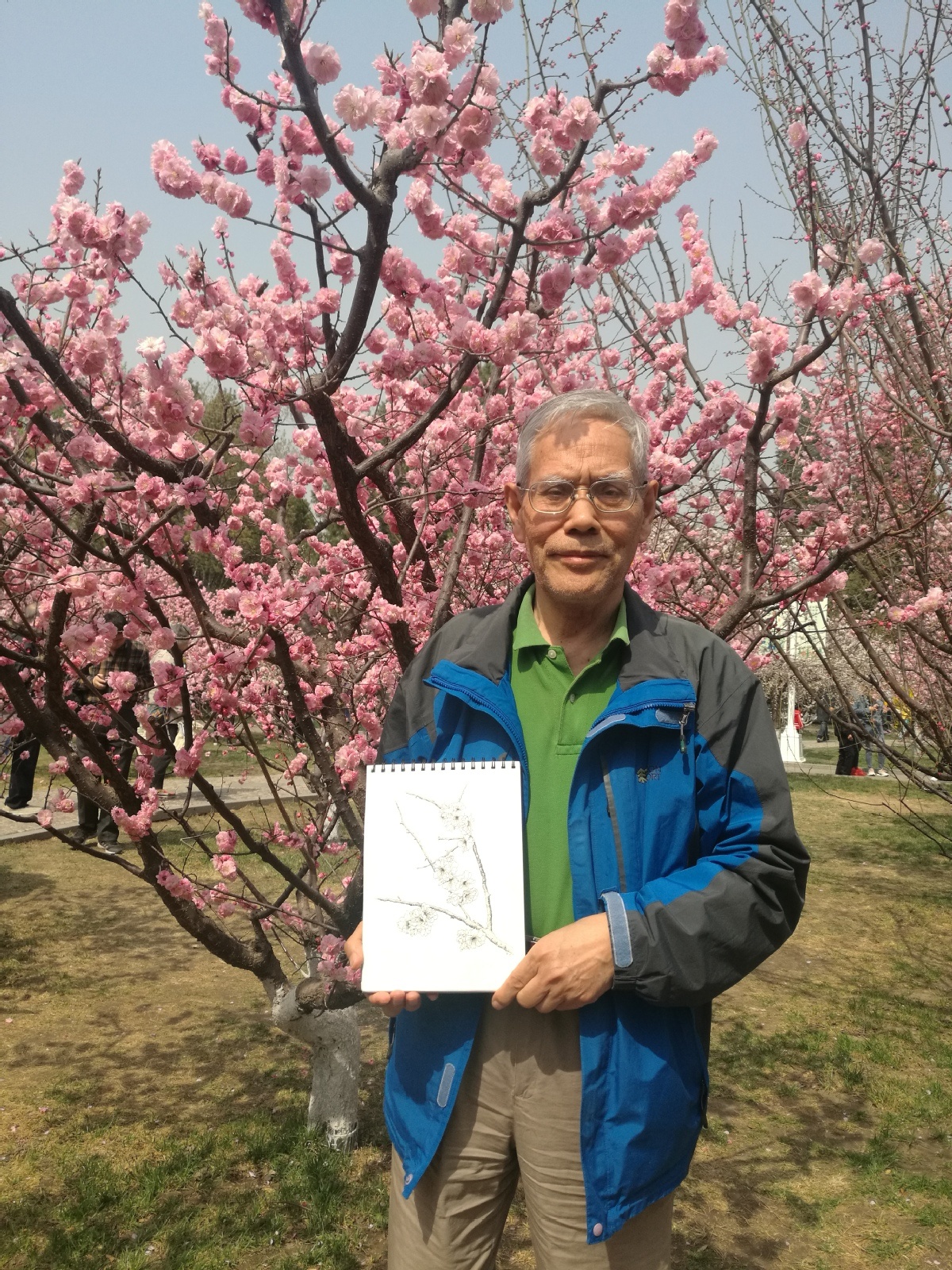

Wu poses with one of his illustrations at Beijing Zhongshan Park. (Photo: China Daily)

After several years of trying different subjects-from postcards to still lifes, landscapes and architecture-he finally decided to focus on botanical illustration. It was a peony that inspired him in 2014.

"At that time, I already had a solid mastery of the basic skills after years of practice. I happened to see a person painting a peony, and I rushed back home to get my gel pens and sketchbook because I wanted to draw it as well," he says.

Wu mentioned the good advice received from Zeng Xiaolian, 81, a veteran botanical artist who had organized many professional exhibitions in recent years. The two only met three times, but Wu said he benefited greatly.

In 2017, Zeng encouraged Wu to register for the botanical illustration exhibition of the 19th International Botanical Congress in Shenzhen, Guangdong province.

"I had to create my first large illustration, about a Chinese dwarf banana. I was elated that it was chosen by the committee, marking my first time participating in an international art exhibition," Wu says.

The success encouraged him to take part in more professional activities to make friends with others who appreciate botanical illustration.

He also shares his skills. He believes his advantage is that he is "not hedged in with rules and regulations because he's never been trained by professionals".

"Our students imitate excellent botanical illustrations in class. Wu helps us a lot and sometimes takes students to a park to draw with him," says Lu Tieying, who teaches painting classes at the University for the Aged, under Beijing's culture and tourism department.

"Wu is very diligent and prolific. He's always in high spirits and we need to follow his example," she says.

On May 31, a special painting exhibition was held at the Wuhan Botanical Garden of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Wuhan, Hubei province. There were 82 botanical illustrations by 48 painters from seven countries, including the United Kingdom and Japan.

Soon after the coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan in January, the committee began soliciting botanical illustrations for the exhibition. It asked painters to depict plants from Hubei, which boasts great plant diversity.

Wu responded to the call and spent 16 days on an illustration of longyoumei, a Chinese plum, a rare species that's known for its naturally twisted stems. His creation was based on a small sketch he had first painted in a Beijing park last year.

About 80,000 visitors attended the exhibition. The committee selected 10 paintings, including Wu's work, and gave an identical copy as a gift to medical workers in Wuhan who had dedicated themselves to the fight against COVID-19.

Chinese plum blossoms in winter and spring symbolize a strong personality that can stand the test of harsh cold. The plant has an upright, noble and elegant character in the traditional Chinese culture.

"The plum blossom is the city flower of Wuhan," Wu says. "The twisted stems signify the spirit of Wuhan citizens who have dauntlessly joined in the fight against COVID-19. Some white flowers are in full bloom, and some are first buds shooting out. It means the city has successfully curbed the pandemic and has a bright future ahead."

Botanical illustrator Wu Qinchang attracts a crowd when he draws at Beijing's Jingshan Park. (Photo: China Daily)

Wu Qinchang, 75, a senior aeronautical engineer from Beijing, enriches his life in retirement by creating botanical art with hands that once assembled airplanes.

For the past seven years, he has frequented Beijing's botanical gardens and parks to draw still-life paintings of various flowers, such as the lotus. He has made more than 710 black and white botanical illustrations using modern gel pens.

In China, botanical illustration is a rare hobby. Originating in ancient Greece, it's a genre of art that depicts the intricate form of a plant, highlighting its particular features with scientific accuracy.

"Drawing botanical illustrations makes me feel good, both physically and mentally," Wu says. "I always take a stroll in a park as exercise before I start."

Wu retired from a State-owned aerospace enterprise in Beijing. In his 20s, he spent five years in a workshop learning how to assemble an airplane.

A self-taught artist, he spent years training himself to draw without an eraser. He never makes a draft with a pencil but uses a common gel pen to render the final image in his sketchbook.

"Observation comes first. The secret is to mark five small black spots on the paper to ensure the rough scope of the flower, and I can have the layout in my head," he says.

Last year he underwent eye surgery for a cataract that had been hampering his work. His sight deteriorated over time to the point that he could only see a blurred image. His mastery of drawing helped to overcome the problem, but eventually he turned to a doctor.

On the back of each illustration, he notes the flower's Chinese and Latin names, its features, when and where he drew it and his thoughts and feelings about it.

Thanks to mobile apps, he can quickly identify species with a simple snapshot. If an app fails to identify some rare species, he searches on Plant Photo Bank of China, a government-supported online website that collects images, filmstrips and digital photos of plants.

He has also made friends with some botanists, who can answer his specialized questions.

Wu enjoys collecting stamps and likes to send a postcard to himself as a travel souvenir whenever he visits a new place.

When he was 62, just two years after retirement, Wu drew a small sketch of Jiangxi province's Sanqing Mountains on a blank postcard, after failing to buy a postcard with a picture. That's when he began to cultivate his drawing talent. He's always interested in learning new things, he says.