Children perform in St John’s Church in London. (Photo: China Daily)

They are turning away from the ‘tiger mom’ stereotype and seeking to motivate and encourage all-round children

A few dozen young Chinese children with big smiles on their faces gave a concert in December under a sparkling Christmas tree, inside the spectacular St John’s Church in London’s Waterloo.

The performance was not perfect in terms of execution, nor were the songs technically challenging. The simple and cozy concert was more about helping the young performers gain confidence, build teamwork skills, and enjoy the happiness of playing music together.

“We are not looking for the next (famed pianist) Lang Lang. We want our children to enjoy playing music, as opposed to practicing music for the sake of passing music grades,” said Xu Zhining, a parent who was one of the ensemble’s founding members and whose 10-year-old son was one of the performers.

The group that practices together regularly and stages three performances a year offers an insight into a new generation of young Chinese parents in the UK; one that is focusing on helping children develop into all-round individuals. The characteristic is less common among parents in China, who have a reputation for being strict, dominating, and results-oriented.

Students learn drawin at Kensington Wade bilingual school in London. (Photo: China Daily)

Xu, like many other Chinese parents who have lived in the UK, has grown to understand, and agree with, the British education system’s ambition to encourage all-round development. Instead, it aims to bring out life skills, such as leadership, teamwork, and other capabilities that cannot be easily measured.

“Overall, Chinese parents living in the UK are more lenient on their children’s education,” said May Huang, CEO of UK Education Weekly, a London-based education-focused Chinese language publication. “That is because they realized that in the UK education environment, a child with great personality and other life skills can gain high achievement and recognition, even if the child does not have top academic grades.”

Such an open environment has encouraged Chinese parents to become more creative with their child-rearing strategies. For instance, some have decided to home-school their children, to facilitate more family time and help them schedule activities more efficiently.

Putting less emphasis on pushing children to come top in school exams has left Chinese children in the UK with more time to do things, such as take Mandarin classes, which tends to be a skill many overseas Chinese parents care deeply about. Consequently, Sunday Mandarin classes are popping up across the country and institutions, such as the Chinese-English bilingual nursery Kensington Wade, have been established to help children become fluent in both languages.

Despite becoming more relaxed about academic achievement, Huang said Chinese parents are still investing more time and energy in their children’s education than the international average.

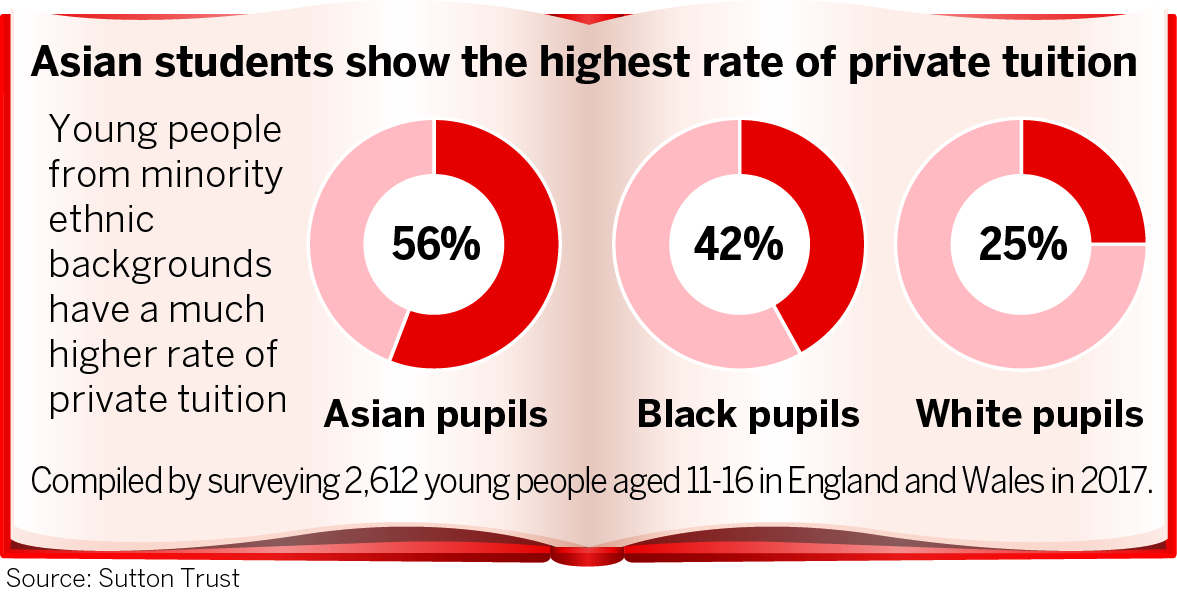

It is an observation backed up by statistics. According to a 2017 report by the research group Sutton Trust, 56 percent of Asian (including Chinese) pupils surveyed have studied with private tutors, compared to 25 percent of white pupils. The survey was conducted by polling 2,612 people aged 11 to 16in England and Wales.

In 2016, almost a quarter of Chinese A-level pupils attained three A-level A grades or better, with three in every five then going on to university. It meant Chinese students in the UK were twice as likely to go to university as white pupils.

On the surface, such evidence points to a continuation of the Chinese “tiger mom” mentality, which was popularized by the Yale professor Amy Chua’s 2011 book Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother.

The book, which immediately became an international best-seller, shocked the Western world with what Chua calls the “Chinese” method of rearing children, which she characterized as having extensive after-school tutoring, relentless music practice, and draconian rules that include no sleepovers, no play-dates, and no grade lower than an A.

In the book, when Chua’s daughter Lulu turns in a poor practice session on the piano, Chua hauls the child’s doll’s house to her car and tells her she will donate it to the Salvation Army, piece-by-piece, if Lulu does not have the passage mastered by the next day. In another instance, she rejects a birthday card from Lulu and demands a better one.

When the book was first published, it provoked outrage, although many Chinese parents such as Xu, found Chua’s approach easier to understand.

At the root of the “tiger mom” approach is the old Chinese adage that hard work leads to success. Chinese culture is full of stories that perpetuate the notion and Chinese parents motivate their children with these stories.

Meanwhile, in contemporary China, the large number of people competing to attend one of the handful of top-notch Chinese universities means the bar is set very high, resulting in parents forcing their kids to study for long hours and at increasingly young ages.

This mentality, which is still in full swing in contemporary China, is not as prevalent in the Chinese community in the UK, where an increasing number of young, internationally minded parents think like Xu.

“I allow my children to follow their interests, and do not impose hard goals on them,” said Mike Wang, a lawyer in London whose 14-year-old daughter plays the piano, clarinet, and guitar, but whose daily combined practice only takes an hour.

Wang’s younger daughter, who is 9, plays the piano and violin.

“Instead of motivating my children to achieve high grades, my dream is that, in the future, we can just sit together after dinner and have a family concert and enjoy the joy of the music,” said Wang.

Alei Duan, a finance professional in London, takes his 8-year-old son to play golf twice a week, in addition to participating in soccer, martial arts, and swimming.

“I do not push him to achieve high scores academically, because I feel it is important for him to grow up as an all-rounded person,” said Duan, who added that he was pleasantly surprised when he realized soccer helped his son develop important teamwork skills.

And, contrary to the traditional “tiger mom” approach of trying to fill every second of a child’s diary, Xu, Wang, and Duan all believe a child’s schedule should include some “wasted time”.

“We should accept that a child should have some time off, just because they are children,” Duan said.

As time goes by, Huang believes more and more Chinese parents will follow this path and allow their children the freedom to develop as all-round individuals.

Looking to the future, he expects the education landscape in China to change too, facilitated by an increasing number of overseas-educated young Chinese parents, and more readily available education resources and information.

“The new generation of Chinese parents, especially those in their late 20s and 30s, are increasingly different from the previous generations,” Huang said. “The increasing emphasis on diversity and customized approaches to bring up their children is beginning to alter China’s education landscape to a model increasingly close to that of the international market. This is indeed a positive development for the future generation of Chinese talents.”

Case study: The home education experience (Jinna Wu and her 8-year-old daughter, Phoebe)

Jinna Wu and her 8-year-old daughter Phoebe display some of the work they produced together. (Photo: China Daily)

Eight-year-old Phoebe is master of her own schedule. Her typical day starts at 8:30 am with about two and half hours of piano and cello practice. In the afternoon, she studies English and math, in line with her school curriculum, and combines them with a selection of elective classes including art, history, science, chemistry, and computing. She also has a 15-minute Chinese language class each day before going out and joining her friends for afterschool activities.

Her tutor is her mother, Jinna, a fashion industry professional who moved to the UK in 2001.

Their “classroom” is not limited to the home. The pair regularly joins other home education families on trips and workshops, visiting sites including the Parliament buildings, the Bank of England Museum, Saatchi Gallery, the gallery at the National Army Museum, the National Maritime Museum, and others.

“We decided to give it a try when we felt Phoebe’s extra music and sports activities, originally scheduled after she finishes school at 3:00 pm, was physically too demanding,” said Jinna. Home schooling meant that music and sports can be done earlier in the day, leaving Phoebe free to play in the evening.

Home schooling is still not common among Chinese parents.

“It took a lot of courage,” said Jinna.

After three terms of gaining experience, Jinna is quite confident about carrying on educating Phoebe at home during her primary-school years, and says she may do the same for Phoebe’s younger sister, Sophie, who is currently aged 2.

And how does Phoebe find the experience?

“I like the variety of activities. I don’t want to go back to school,” she said.

Basic info

About Jinna: A fashion industry professional who came to UK in 2001 and who is now a full-time mom and Phoebe’s homeschool teacher.

About Phoebe: An 8-year-old who has demonstrated a passion for music and who also enjoys badminton and swimming.

Case study: The bilingual education experience (Chen Xinghuaand his 3-year-old son, Harry)

Chen Xinghua, his 3-year-old son Harry and 1-year-old son Quinn share a moment with the boy’s mom Stephanie Tsang. (Photo: China Daily)

Chen Xinghua admits he once felt torn over the issue of how much academic pressure to put on his 3-year-old son, Harry.

“My mother would put pressure on Harry to recite Chinese poetry, because she belongs to that generation of Chinese parents who believe in giving kids an early start. But what I realized is that Harry can learn Chinese just as well when he is watching kids’ television,” said Chen, who is a great believer in the importance of taking the learning out of the classroom.

In the evening and at weekends, Chen plays with Harry and his one-year-old brother Quinn at home. At the weekend, he takes them to the park on family trips.

He feels that Harry’s classroom schedule is already full and that arranging additional academic or serious extracurricular activity would be counter-productive.

But Chen has expectations for Harry in other areas. He feels it is most important for his son to maintain a reasonable standard of Mandarin usage and for him to remain in touch with his Chinese roots.

“It would help him build a sense of identity, and having those connections could help his future career development too,” said Chen.

To help meet this need, Chen sent Harry to London’s first bilingual school, Kensington Wade, where Chinese and English are taught in parallel, in two separate classrooms.

The school schedule is not packed, but Chen has been pleasantly surprised to see Harry’s ability in the Chinese language reach a similar level to that of children of his son’s age in China.

Basic info

About Chen Xinghua: A finance professional who studied in the UK before returning to Beijing for a few years of work. He now lives in London with his wife and two sons.

About Harry: A polite 3-year-old who always has a big smile when his dad mentions “it is time to go to school”.