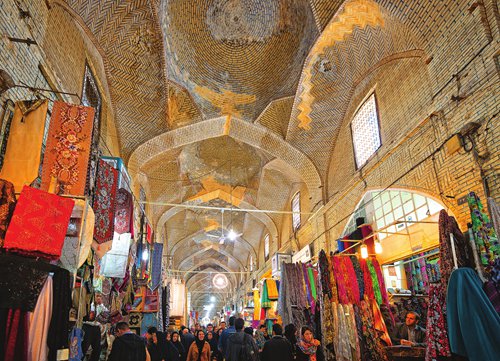

Vakil Bazaar in Shiraz, Iran. ( Photo: VCG)

On the very last day of 2018, Wu Yi boarded a flight home and said goodbye to Tehran, the city she spent the past five years in. The Chinese woman came to Iran to start a travel agency in 2014 with her ambition to "dig for gold from this untapped market."

Three super-big suitcases were around her, filled with items that she thought would support her for at least 10 years in Iran. But the sudden withdrawal of the United States from the Iran nuclear agreement in 2018 crushed her plans and dreams in an instant.

She called her five years in Iran "a moon reflection in the water", which is indeed a beautiful mirage.

She had high hopes when she entered the Tehran market in 2015. Her business flourished in 2016, as many Chinese clients visited for business trips. However, her optimism faded over the past year as many orders have been canceled, and financial transactions faced difficulty.

She is not alone. A large number of Chinese merchants took a ride on this roller coaster. Some departed and others remained, amid the ups and downs of the mercurial international situation.

A lot of foreign businesses coming to Iran for opportunities have left the country since the US withdrawal from Iranian nuclear deal, due to the resulting fluctuating interest rates, soaring rents, or simply deterred by hardline US rhetoric against Iran.

US sanctions reportedly hurt the Iranian economy and devalued the Iranian rial, but also exerted some impact on Chinese firms operating in Iran.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Geng Shuang said in May 2018 that China and Iran maintain normal economic ties and trade.

The leaders of Britain, Germany and France have declared their backing for the Iran nuclear deal renounced by the US.

Signed in 2015 between Iran and a group of world powers - China, the US, Russia, France, the UK, Germany and the EU - the deal ended decades of economic sanctions and led to heavy investment flowing into Iran.

The castrated hope

The year 2016 was a prime period for the Iranian market, with an influx of various types of Chinese enterprises to explore post-sanctions Iran.

According to data Wu Yi obtained from the airlines and the embassy, before 2015, the number of Chinese tourists to Iran was less than 50,000 every year. But with the lifting of the sanctions on Iran in 2016, the number of Chinese tourists to Iran reached about 70,000 in 2017, of which 60 to 70 percent were business tourists.

"After the Iran nuclear agreement, Chinese hotels and restaurants sprung up in Tehran, where hotel beds were in a high demand. Many Chinese were invited to Iran for trade. People were full of enthusiasm and hope for this mysterious land," Wu told the Global Times.

The unexpected boom in Iran's market when sanctions were lifted left many deals already made hanging in doubt, pushing many Chinese companies who have been there on the back foot. Their Iranian partners were starting to pick out better partners among a large number of competitors.

A Chinese trader who came to Iran in early 2012 told the Global Times that many of the Chinese companies' Iranian partners tore up the signed contracts.

Such a situation has impacted China-Iran cooperation in energy, infrastructure and other fields.

"Only one year later, the fever subsided. Not many entrepreneurs around the world were really determined to put their money in this 'risky' land. Iranians are turning back to Chinese businessmen again for taking over deals," the entrepreneur who requested anonymity told the Global Times.

"For one reason, international financial sanctions against Iran had not really been lifted during that time. In short, Iran cannot make normal financial transfers to the outside world," the entrepreneur said.

"The Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering (FATF) even named Iran as a high-risk country for money laundering. The flow of funds for trade and investment with Iran is extremely difficult," he said.

"That in the end put a lot of people off," he noted.

The bank stopped handling yuan-denominated Iranian payments to China last November, according to a report by Reuters confirmed by Chinese entrepreneurs.

"It has been said that this channel will be opened again soon, but no formal notification has been received. This disturbed the normal production and trade of Chinese enterprises," a Chinese businessman, surnamed Wang, told the Global Times.

"The culprit is American capricious unilateralism," Wang said.

A roller coaster

Wang rushed into Iran in 2016 at the prospect of local infrastructure boom, among a group of Chinese swooped into Tehran due to the irresistible lure of its market. But they fast turned to worries as the US quit the agreement in 2018, and Chinese enterprises now dread that sanctions reimposed on Iran could affect them.

It made many Chinese companies, large or small, reevaluate the market.

Chinese businesswoman Liang has a business selling Inner Mongolian melon seeds. It has long been a favorite snack among Middle Eastern residents, and Iran has also been a major exporter of her products.

However, since the middle of 2018, due to the fear of US sanctions affecting the sales of her products in other parts of the Middle East, Liang finally chose to temporarily abandon the Iranian market and wait for a brighter moment.

But she believes that the crisis may bring opportunities for those who always stay in Iran's markets. One of her counterparts who never wavers away from the Iran market has made so much money there that she can afford to buy seven apartments in prime locations in Shanghai, she said.

Guo Yong, head of the Iranian office of Rongshang Logistics, the largest Chinese cooperative agent of Islamic Republic of Iran Shipping Lines, told the Global Times, "In the current situation, China's large multinational shipping companies are unlikely to lose Western markets in order to stay in Iran because of their need to balance the global market. Private logistics companies like us are looking to fill the void left by departing companies."

In addition to the dilemma of leaving or remaining, the unstable domestic financial status is another major factor shaking people's confidence.

"Exchange rates fluctuate as much as 20 percent in a day. The level of the devaluation goes beyond expectations. Dealers would rather keep goods in a warehouse than selling and have the profits immediately devalued. This was absolutely beyond our imagination when we came here in 2016," Wang said.

Wu Yi can feel the slump of business fairs and tours since Trump tore up the Iran nuclear deal and reimposed sanctions. She said once popular Chinese hotels are now mostly on sale.

Internal market depressed

In addition to external pressure, the Iranian market's own problems also worry a lot of Chinese investors, such as a tedious submission and approval process at the border.

"We have to spend three or four days a week in handling formalities. The process is too trivial, so we specially hired a local to be fully in charge of approvals," said Wang.

"Moreover, customs policy varies a lot, even within a week. If you are not informed, your goods may be detained in customs for a long time. It's hard for many Chinese to bear the cost," he continued. He said the customs detentions can also be the result of trade protectionism in Iran.

On June 20, 2018, the Iranian industry minister forbade imports of 1,339 kinds of goods, since the goods have similar domestic rivals. Some banned products include home appliances, textile products, footwear and leather products, furniture, healthcare products and machinery, reported the Tehran Times.

Around the days the ban was announced, Iran's main port, Bandar Abbas, was holding about 140,000 tons of cargo awaiting clearance. Most of these goods were affected by the ban, harming thousands of small- and medium-sized enterprises in China, Guo Yong said in a previous interview with the Global Times.

After the US withdrew from the Iran nuclear agreement, the situation inside and outside Iran has become grim. Many Chinese companies have struggled to find a way to survive the Iranian market.

"Many of my friends who left said they would rekindle their business someday when the political situation turns bright. They dream of a renaissance in trade with Iran for this promising market with a population of 80 million," Wang said. "Moreover, Persian businessmen are enthusiastic, far away from demonized representation by the Western media."

While reaffirming opposition to unilateral sanctions, China is experienced in protecting the legitimate interests of its companies that have business in Iran when the country was under sanctions.

Wang himself plans to expand markets in neighboring countries while sticking to the Iran market. "It's not easy to run a business in a far land," he says. "I won't give up easily."