What causes some people to break out in hives after eating shrimp or to sneeze uncontrollably during pollen season? These common symptoms result from one of the body's most rapid and intense defense mechanisms: an allergic reaction. Recently, scientists at Zhejiang University have discovered a method to harness this robust response—not just targeting food or pollen, but directing it against cancer.

Their study, titled "Sensitized Mast Cells for Targeted Drug Delivery and Augmented Cancer Immunotherapy," was published in Cell on December 9. The research was led by Professors Zhen Gu and Jicheng Yu from the School of Pharmacy at Zhejiang University, together with Professor Fujian Liu from the First Hospital of China Medical University. Dr. Yan Xu of Zhejiang University is the study's first author.

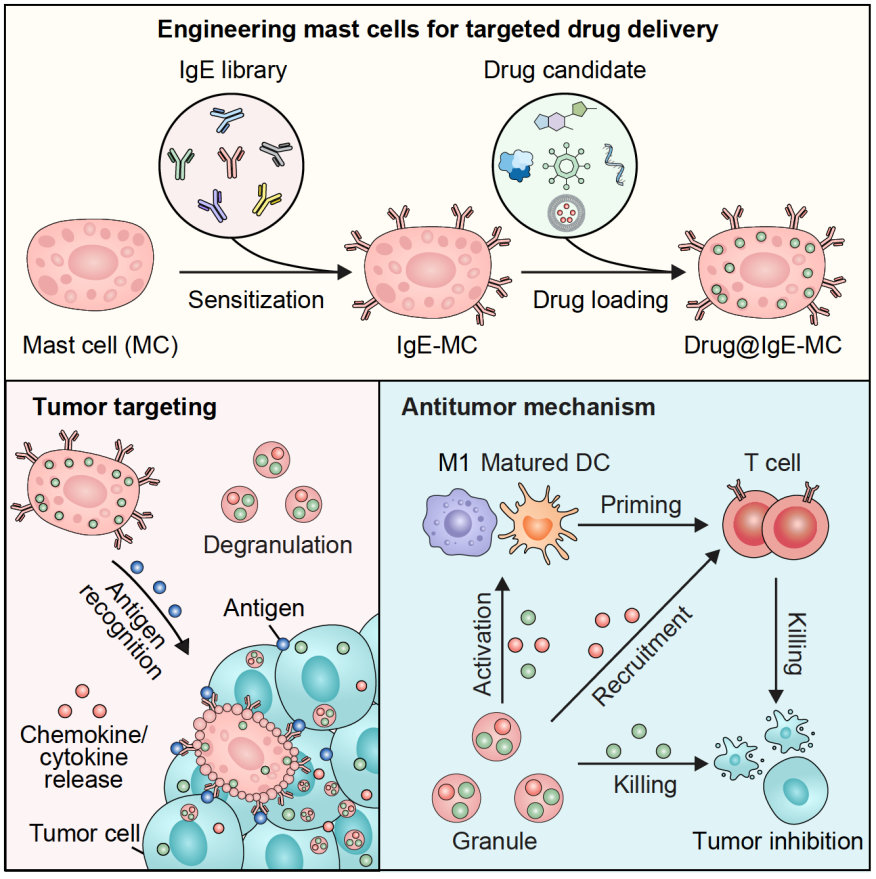

Infographic illustrating the engineering of mast cells for targeted anticancer drug delivery.

Turning allergy cells into cancer hunters

The research focuses on mast cells, which are immune cells primarily known for their role in allergic reactions. These cells contain small packets of inflammatory molecules and can respond within seconds when activated. Instead of allowing mast cells to react to allergens, the team "retrained" them using IgE antibodies that recognize proteins found on tumor cells.

When these customized mast cells are injected into the bloodstream, they travel to tumors. Upon detecting their specific cancer target, they release bursts of inflammation, triggering a rapid, allergy-like reaction within the cancer. This sudden activity helps "wake up" the immune system, transforming quiet, hard-to-treat tumors ("cold" tumors) into "hot" ones that immune cells can recognize and attack.

A living delivery system for cancer-fighting viruses

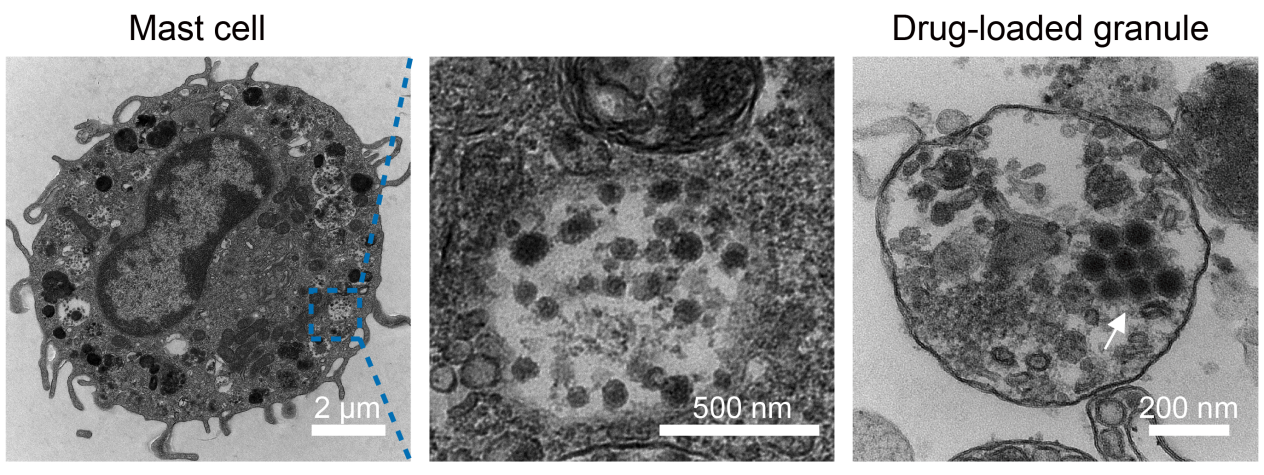

The researchers also discovered that mast cells can act as living carriers for oncolytic viruses—viruses that selectively infect and kill cancer cells. By hiding these viruses within mast cell vesicles (granules), the team protected them from destruction in the bloodstream. Once the mast cells reached the tumor and became activated, the viruses were released from the cells.

In mouse models of melanoma, breast cancer and lung metastasis, this approach drew more cancer-killing T cells into the tumor and inhibited tumor growth.

Electron microscopy image of oncolytic virus–loaded mast cells.

Personalized "tumor allergy" therapy

The strategy also proved effective in patient-derived tumor models. Human mast cells loaded with IgE antibodies that specifically target HER2 (a standard tumor marker) and oncolytic viruses triggered strong T-cell responses and notable tumor suppression, suggesting that simply matching IgE antibodies to a patient's unique cancer markers could quickly create a personalized therapy.

A platform for various types of treatments

Beyond viruses, mast cells can carry a wide range of therapies—including drugs, proteins, antibodies and even nanomedicines—and release them only when they encounter the tumor. This means the platform could one day support multiple treatment modes within a single cell therapy.

What's next

The team plans to develop a workflow for selecting the right IgE antibodies for each patient, scale up manufacturing of therapeutic mast cells and explore combinations with existing cancer immunotherapies. Their goal is to bring the idea of "making cancer allergic" from the lab bench to the clinic, offering a new option for patients with tumors.