Photo:CGTN

Photo:CGTN

Every spring, millions of visitors flock to Japan to soak in the seasonal spectacle that is cherry blossoms, or sakura, the country's quintessential flower. Outside Japan, another popular place to admire the pale pink beauty is the city of Wuhan in central China.

Before the novel coronavirus outbreak hit it, Wuhan was better known for its accessibility and top-tier educational institutions. The 127-year-old Wuhan University, which boasts scenic views of green hills and the sprawling East Lake, is home to some 1,000 cherry blossom trees, making the campus a top attraction in the country during the flowers' blossoming season.

However, Wuhan's cherry blossoms originated during the Chinese People's War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-1945), according to Wu Xiao, founder of Wuhan University History Research Institute. The earliest trees were introduced to the city by the Japanese in the 1930s when Imperial Japanese troops invaded China and occupied the central industrial hub.

Since then, these flowers have borne witness to a history of struggles and renewals between the two Asian countries.

Symbol of war

In 1938, Japanese invaders captured Wuhan, after carrying out a brutal massacre in the former Chinese capital Nanjing and chasing the Nationalist government inland in the previous year.

Most students and faculty staff at Wuhan University had evacuated the city before the Japanese came. But five people left behind to watch over the university, one of whom was a lecturer named Tang Shanghao.

Tang, who studied in Japan and married a Japanese woman, was tasked with safeguarding the university by negotiating with the occupying troops. The Japanese later turned parts of the university into a field hospital, sparing the campus from war damages.

A Japanese general named Takahashi agreed not to damage university properties but wanted some cherry trees to raise the morale of soldiers.

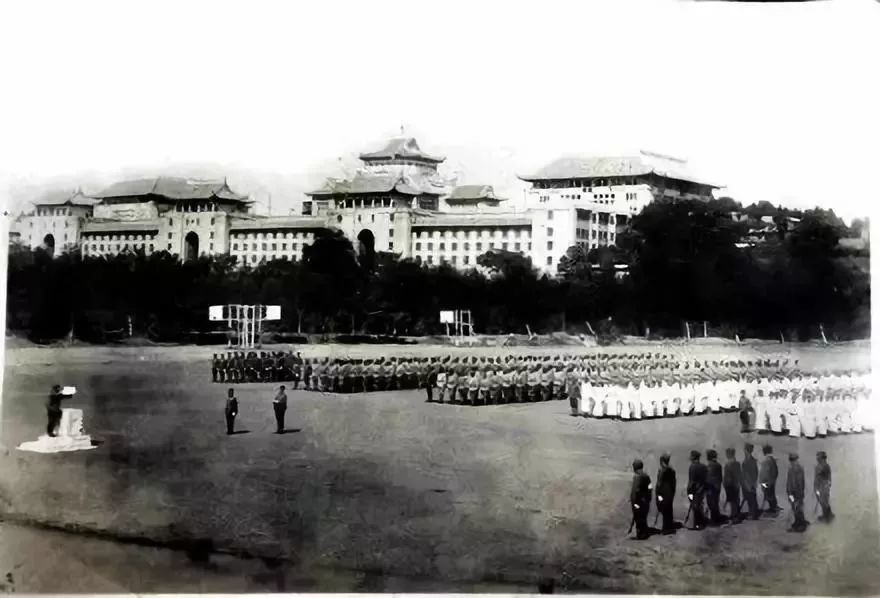

Japanese troops in Wuhan University around 1939. (Photo:courtesy of Wuhan University)

Historians studying pre-war Japan have noted the symbolism of cherry blossom in Japanese militarism. During the period of imperial expansion, Japanese soldiers were told to "die like beautiful falling sakura petals," which symbolize the fleeting nature of life, and cherry trees were planted to console the souls of warriors.

Though feeling resistant, Tang couldn't say no. But when he suggested also planting some plum blossoms, a flower symbolic of China, Takahashi refused.

In the spring of 1939, more than 20 Japanese cherry blossom trees were planted along today's Cherry Blossom Avenue at Wuhan University. Besides the university, an archive photo shows that some cherry trees also grew on the Yangtze River bank in Hankou.

This first batch of cherry trees survived after the war. In 1947, when exiled Wuhan University staff and students returned to the campus to see the trees in bloom, they were conflicted. Eventually, it was decided that the trees ought to be kept as a reminder of the Chinese people's suffering at the hands of Japanese invaders.

Cherry blossom trees at Wuhan University in 1947. (Photo:courtesy of Wuhan University)

It should be mentioned that cherry trees typically have a lifespan of 15-20 years, meaning the first cherry trees planted at Wuhan University would have died out by the 1960s.

Token of goodwill

But the story of cherry blossom continued in Wuhan. After China and Japan normalized diplomatic relations in 1972, then Japanese Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka gifted 1,000 Prunus Sargentii cherry trees to former Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai as a token of goodwill. A few dozens of those were then planted at Wuhan University, where Premier Zhou once lived.

Afterward, at the 10th and 20th anniversaries of the establishment of Sino-Japanese relations, civilian organizations and the private sector in Japan donated hundreds of cherry blossom saplings to Wuhan, all of which flourished on the Wuhan University campus.

Between 1987 to 1992, a group of former Japanese war prisoners brought more cherry trees to Hubei, with Wuhan serving as the capital, to thank the locals for their merciful treatment after Japan's surrender.

Revisiting Wuhan University in 1985, Tang stopped at the spot where the first cherry trees were planted. "Although they were planted by the enemies before, the trees were innocent and should live and prosper," he said. Recalling his recent trip to Washington, D.C., Tang said he saw cherry blossoms gracing the U.S. capital.

"Now, the scenery transcends national borders," Tang said.

Blossoming cherry trees at Wuhan University in March during Wuhan's lockdown. (Photo:VCG)

Hope and regeneration

In spirituality and popular culture, the cherry blossom is widely regarded as a metaphor for the brilliance and fragility of human life as well as nature's cycle of regeneration. Although short-lived, the flowers are nonetheless harbinger of spring and the blooming a powerful sight to behold.

In the spring of 2020, no place needed the message of hope like Wuhan, the first city to be locked down and suffer grave losses due to COVID-19. Wuhan's plight brought China and Japan into solidarity, as the two countries actively supported each other with donations of medical supplies in their battle against the epidemic.

A Japanese girl in a red Chinese cheongsam bows to passersby with a donation box in hands to raise money to help those in China affected by the coronavirus in Tokyo, Japan, February 8, 2020. (Photo:Xinhua)

In February, a line of classical Chinese poem which reads, "Different lands, same sky" written on the boxes of donations from Japan went viral in China, as social media users welcomed the verses, a nod to the two countries' ancient cultural ties, as a show of appreciation for the Chinese language.

In June, Japanese filmmaker Takeuchi Ryo's documentary "Long Time No See, Wuhan" chronicling the city's post-epidemic recovery became an instant hit in China, winning praises for the film's neutral and humanistic portrayal of Wuhan residents.

Nevertheless, even with some signs of thawing, the relationship between China and Japan has always been complicated, mostly due to unresolved wartime grievances, while also entangled with the U.S. geopolitical interests in Asia.

History shows that the two countries have been in darker places before. Now, as both countries try to emerge from the pandemic and a state visit planned, it is hoped that they will have another spring to look forward to.