Wang Sicheng, 37, who lives in Gansu province, said during an interview with Xinhua News Agency his family decided to scrap plans to have a second child because of the cost of education.

"My only child, who is 5, is now enrolled in eight off-campus classes, including Go chess, Lego and swimming. These classes cost about 60,000 yuan ($9,286) each year," he said.

Born in the countryside, Wang Sicheng never took such classes during childhood and briefly considered relieving his child of the burden. "However, everyone else is learning. If we do not follow suit, I am worried that my kid will fall behind," he said.

He and his wife had long concluded that one child had already imposed significant financial pressure on them and that they did not want to have another.

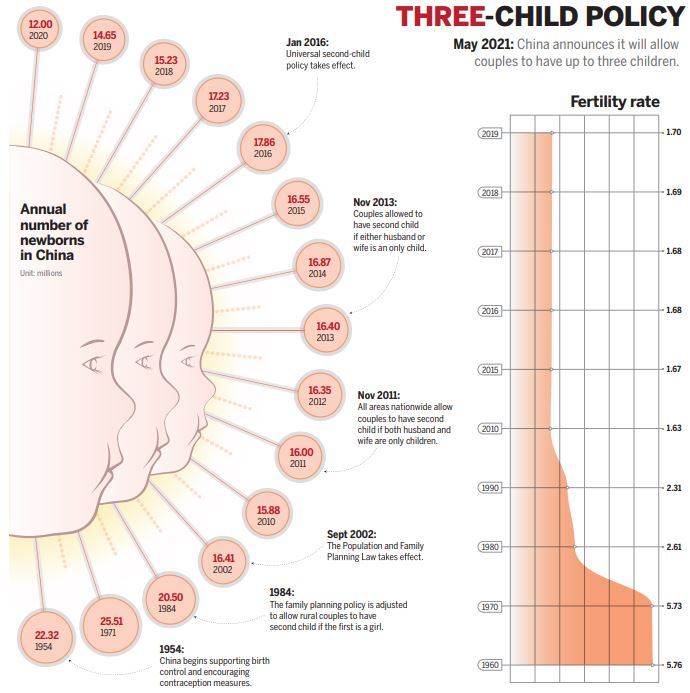

On Jan 1, 2016, China began implementing the second-child policy, officially ending a decadeslong rule allowing couples to have only one child.

However, like Wang Sicheng, a considerable number of families open to the idea of having two children had eventually given up. Of these families, 75 percent cited financial concerns as a key factor in their decision, the National Health Commission said, quoting a survey in 2019.

An online poll of some 30,000 participants, carried out from May 12 to June 11, also highlighted the mounting economic pressure.

The poll, conducted by news outlet ifeng, shows that housing prices, child-raising costs, education and medical expenses are among the top factors affecting respondents' decisions to have children.

Asked about measures that might increase their willingness to have children, financial support ranked the highest. Free kindergarten classes and preschool education, along with subsidies for child-raising, having a second child, and maternity services were also near the top of the list.

Yuan Xin, a professor of population studies at Nankai University in Tianjin, said: "According to an old saying in China, 'one more baby just means one more pair of chopsticks'. That pair used to be made of bamboo, now it is made of gold, and in the future it might be made of diamonds."

For many working mothers, finding sufficient time to take care of and connect with their children has become a problem.

Xu Rui, 29, a civil servant in Jiangsu, said that after discovering her 1-year-old daughter had minor heart defects, she decided to take her to Shanghai for treatment, even though this meant she had to miss work, sacrifice some of her leisure time and pay for costly medical treatment.

"At least my parents-in-law can help me raise her, so I can basically keep my life on track without overstressing," Xu said.

However, she sees herself as being in a precarious situation.

"Last year, my parents-in-law had to leave for a short period to look after their parents. The pressure suddenly fell on me and my husband. If that happens again, one of us will have to take time off work to stay home and look after our child," she said. "It's like a butterfly effect, where a minor glitch could cause great disruption to our lives."

With people seeking a work-life balance, nursery services are in high demand, but such facilities remain unevenly distributed nationwide.

He Dan, head of the China Population and Development Research Center, said a survey led by the center showed that 30 percent of families with a child age 3 or younger are in need of child care services, but official data show that only 5 percent of such children are sent to nursery care facilities.

"Less than one-in-five nursery institutions are public or affordable for many people. Most of them are in the private sector and relatively expensive. It is estimated that less than one-third of families in need can afford them," she said.

A nurse weighs a baby at a hospital in Nanning, capital of Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region. (Photo: Xinhua)

Lack of child care services, cultural shifts cited for decline

English-language teacher Yang Mengqi, who is in her late 20s, does not want to have a child for at least three years.

Her students, who are in their first year at senior high school, are on track to sit in the all-important gaokao, or national college entrance examination, in 2023, and Yang sees her short-term priority as making sure they go to the universities of their choice.

"I became a teacher about four years ago. It's a job that I hold close to my heart," said Yang, who married in October. "In the daytime, I give lessons, and in the evenings, I prepare teaching materials. I don't think I have much time and energy left to raise a child."

Yang, who hails from Jiangsu province, has witnessed the anxiety and pressure faced by relatives and close friends in raising children.

"They look exhausted to me as they fret about which kindergarten they should enroll their children in and shuttle between extracurricular tutoring schools on weekends. The kids are also tired out," she said.

On May 31, China announced that couples would be allowed to have three children, up from two previously.

The National Health Commission said in a statement released the day after the new policy was announced that on average, Chinese women born in the 1990s, such as Yang, will have 1.66 children, a fall of 10 percent from women born in the 1980s.

Among women of childbearing age, defined as 15 to 49, the ideal number of children per couple is 1.8, Ning Jizhe, head of the National Bureau of Statistics, said during a news conference in May.

Last year, the actual fertility rate, meaning the number of children born to each woman, stood at only 1.3, Ning said.

The number is low, as the global average is about 2.5 and the replacement rate for maintaining a stable population is 2.1. It also marked a decrease from an estimated rate in China of 1.6 from 1996 to 2016, according to a report released by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in 2019.

Officials and experts said heavy economic burdens, a lack of child care services, along with cultural shifts have driven the downturn in the fertility level.

Wang Guangzhou, a researcher at the academy's Institute of Population and Labor Economics, said, "I think education costs-including school enrollment fees-pressure to buy houses in school districts, as well as changes in the value of child education, have played a significant role."

This long-standing issue had previously been obscured by the one-child policy, Wang said, adding, "It was not until family planning policy was gradually relaxed that we began to realize the fertility behavior of people nowadays has changed profoundly and needs more attention."