From the People's Daily App.

This is Story in the Story.

The "Four Treasures of Study"-a high-quality writing brush, ink stick, paper and ink slab-have been sought after by ancient scholars and today's enthusiasts of calligraphy and Chinese painting.

When deciding to buy one, they can make a decision judging from its geographical indication.

Chengni ink slabs produced in Jiangxian county, Shanxi province, are a favorite of enthusiasts.

Chengni ink slab is one of the top four ink slabs in China, along with duan in Zhaoqing, Guangdong province, she in Shexian, Anhui province and taohe in Zhuoni county, Gansu province.

The technique for making the clay-fired ink slab is said to date back to the Han Dynasties (206 BC-AD 220). Its production reached a peak during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Today’s Story in the Story looks at the four treasures of study and how they’re being brought back to prominence in China.

Lin Tao, a chengni ink slab master, shows a piece of his artworks. (Photo: CHINA DAILY)

Unlike other ink slabs, which are made from natural stone, chengni in Jiangxian is produced by firing a silt-rich clay collected from the riverbed of the Fenhe, the second-largest river in Shanxi province.

Chengni ink slabs also feature elegant shapes and delicate engravings, which make them valuable pieces of art.

However, if not for the efforts of father and son craftsmen like Lin Yongmao and Lin Tao, a piece of chengni ink slab cannot be easily bought.

The craft was lost during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), meaning buyers and collectors could only select from the ancient relics from the several dynasties prior.

Lin Yongmao and his son decided to revive this ancient technique in 1986. The father and son visited many libraries to read historical documents and many museums to study exhibits.

They learned that to make chengni ink slab, they needed to master knowledge in many fields. This included chemistry, physics, painting, engraving, calligraphy and literature.

After much trial and error, they succeeded in making three chengni ink slabs in 1991. In 1994, their ink slabs won a gold prize at the China Expo of Famous Ink Slabs.

The father and son were recognized as Shanxi folk art masters by the provincial government in 2006.

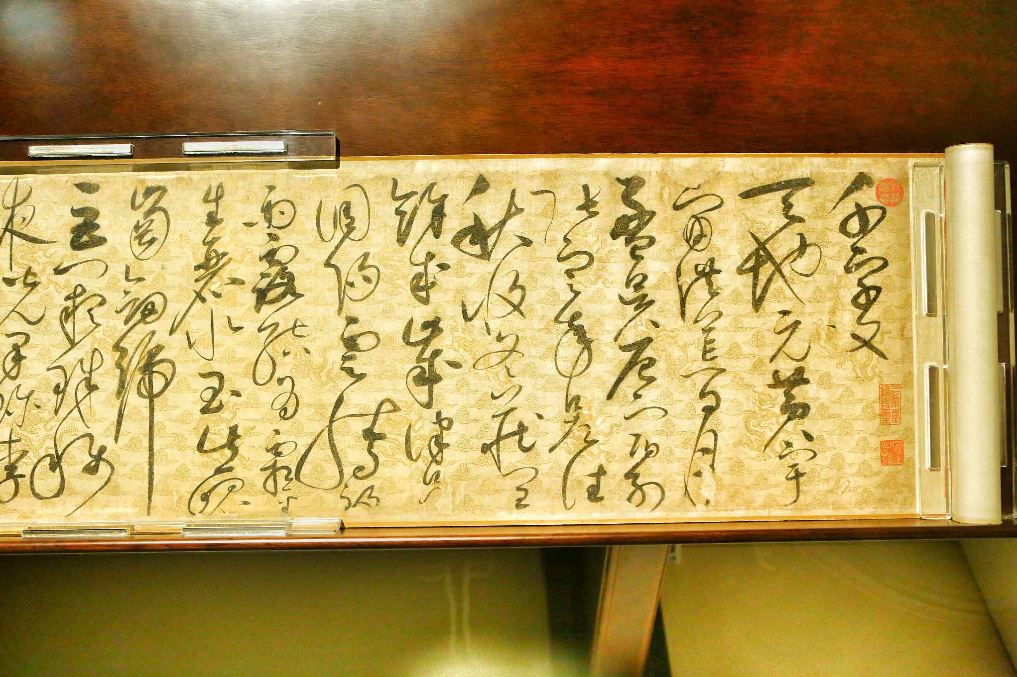

A cursive script work of Emperor Huizong of Song of China. (Photo: VCG)

To help people learn about the artworks and production techniques, the Lins have displayed their ink slabs in a number of exhibitions and held many training sessions.

"I have been fond of chengni ink slabs for many years and finally got one during the Shanxi Cultural Industry Expo last December," said Zhang Hong, a 24-year-old calligraphy enthusiast from the provincial capital of Taiyuan.

"Brush writing with ink ground from a chengni ink slab is a totally different experience," Zhang said.

Calligraphy was the visual art form in traditional China.

Since the invention of the "Oracle bone script," Chinese calligraphy has experienced several development stages, from "Seal script" to "Clerical script," "Cursive script," "Regular script" and "Running script."

There are a large number of calligraphers and calligraphic works that were produced and helped constitute a profound tradition of Chinese calligraphy at each stage.

The clerical script changed the writing style and aesthetic trend of Chinese characters, thus laying a foundation for the evolution of the regular script and opening a field for the development and prosperity of Chinese calligraphy.

In modern times, the regular script is still the standard of writing Chinese characters. Over time, Chinese characters gradually became a system of symbols with strong national ties.

For the better promotion of Chinese character culture, China established the National Museum of Chinese Writing (NMCW) in 2009, in Anyang City, Henan Province, where the oracle bone script originated.

The NMCW is a state-level museum constructed upon the approval of the State Council for preserving, showcasing and studying cultural relics.

(Produced by Nancy Yan Xu, Brian Lowe, Lance Crayon and Da Hang. Music by: bensound.com. Text from China Daily and CGTN.)