From the People's Daily app.

And this is Story in the Story.

The ancient Chinese board game Go is making a comeback.

Go, known as weiqi in Chinese, involves black or white stones being placed in an attempt to outmaneuver and surround the other player's pieces. Despite having relatively simple rules, it is a complex game.

For more than two millennia, Go was considered one of the "four accomplishments", along with the guqin - a stringed musical instrument - calligraphy and painting, that had to be mastered by Chinese men since the time of Confucius (around 500 BC). The game's popularity later declined during the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) when it was considered an "archaic intellectual pursuit".

However, observers point out that the market for "Go education" is booming as parents increasingly realize the benefits of the game.

Today's Story in the Story looks at the re-emergence of Go as a learning tool for students right across China.

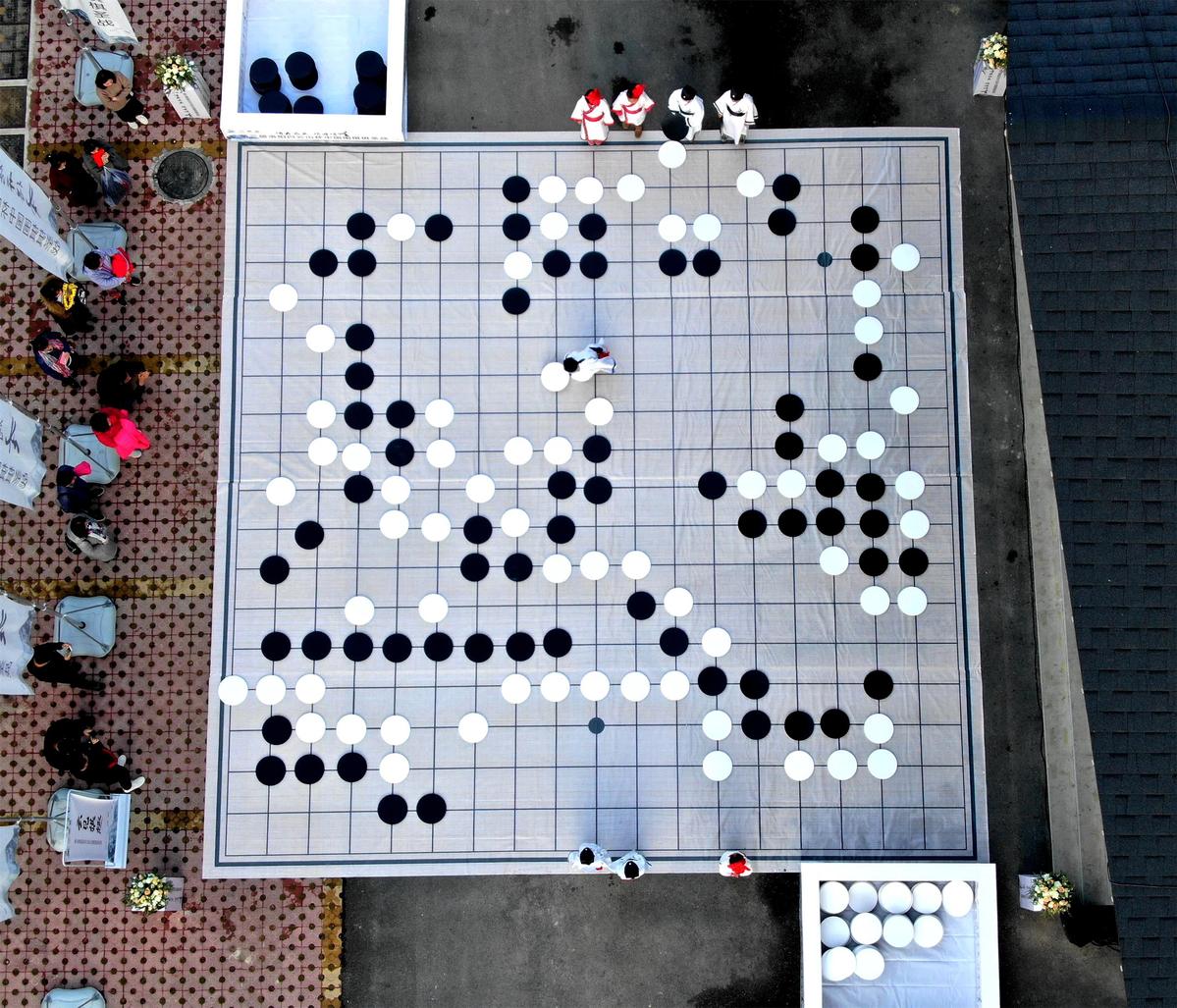

An amateur Go competition held in Luoyang, Henan province, in November featured a giant board, with each player fielding pieces 40 centimeters in diameter. (Photo: China Daily)

Wang Jianhong, a professional player who founded China's first Go club in 1997, said the education industry related to the game started to take off in about 2003.

"At the time, there were not as many extracurricular programs as there are now. As a result, Go, a traditional Chinese game that had always been known to be beneficial in developing the mind, was among the top choices for most parents," he said.

Wang Xiuqiao, from the Qingdao Go Club in Shandong province, offered a similar observation.

"Go would appear to be an obvious extracurricular option for children because their parents, who grew up admiring Nie Weiping, are probably fans of the game themselves," he said.

Nie has been largely credited for kick-starting the game's revival in China in the 1980s after his triumph at the inaugural World Amateur Go Championship in 1979.

He went on to lead China to victory for two consecutive years in the China-Japan Supermatches, beating several top Japanese players including his teacher, Fujisawa Hideyuki. Nie even earned the nickname "Steel Goalkeeper" for his prowess in chalking up wins despite being the only Chinese player left in the tournament.

His achievements in Go have been compared with the Chinese women's national volleyball team that won five consecutive world championships in the 1980s.

During that decade, the popularity of Go rose to new heights as many younger people started to learn to play the game.

Clubs, academies and tournaments devoted to the game mushroomed across the country to meet the growing demand. The demand for classes continued to grow in the new millennium when middle-class families became wealthier and started to prioritize their children's education.

The world's top-ranking professional player Ke Jie loses 3-0 to AlphaGo in a contest in 2017. (Photo: XINHUA)

According to the China Go Institute, the number of players in the country has risen from 25 million in 2009 to 40 million. Statistics from the institute, which organizes the certification test for players, also show there has been a 30 percent annual rise in the number of dans, the master rank in Go, issued since 2015.

Wang estimated that in 2017 at least 100,000 professional teachers from more than 200,000 facilities in China were offering Go training.

BestGo, a training institute in Shanghai targeting preschool and school-age students, is among those that have sought to capitalize on the benefits the internet offers for Go education. Founded in 2011, it has more than 4,000 students enrolled in over 20 branches across cities in the Yangtze Delta region.

Shen Yao, the founder of BestGo, said each student has an account on a server that allows them to perform a question-based exercise or take part in a game with another player. The server automatically pits players with similar levels of skill against each other.

"In the past, players would have been very lucky to find such opponents. But the internet has allowed such matches to take place at almost any time," said Shen, adding that there has been a significant rise in interest among parents in enrolling their children for Go training.

"Go is easy to pick up but it takes years to master. It usually takes at least two years for a beginner to become an enthusiast who relishes the joy of thinking critically when playing the game," Shen said.

One of the key challenges it has faced over the past decade is the lack of qualified teachers - it wasn't until 2016 that Go was offered as a major in universities nationwide.

Despite the challenges, insiders are optimistic about Go's development.

Lin Jianchao, chairman of the Chinese Go Association, has said on many occasions that the game in the country has reached "another historic peak."

(Produced by Nancy Yan Xu, Brian Lowe, Lance Crayon and Da Hang. Music by: bensound.com. Text from China Daily.)