From the People's Daily app.

And this is Story in the Story.

The Great Canon of the Yongle Era, commonly known as the Yongle Dadian, is believed to be the most comprehensive handwritten encyclopedia ever assembled, consisting of 22,937 rolls in 11,095 volumes with 370 million Chinese characters.

It is believed that if the average person wanted to read it in its entirety, they would have to read one volume a day for 30 years.

Only two copies are known to have existed, the original, commissioned by Zhu Di, known as Emperor Yongle (1360-1424) from the Ming Dynasty in 1403, and a handwritten copy completed during Emperor Jiajing's reign (1521-66).

Yet somehow the original manuscript disappeared.

Today, roughly 400 volumes of the copied version, less than four percent of the total, have been collected worldwide.

The question now is, have the remaining volumes survived over the years, and if so, where are they?

Today’s Story in the Story looks at the world’s largest handwritten encyclopedia ever put on paper, the Yongle Dadian, and the mystery surrounding its whereabouts.

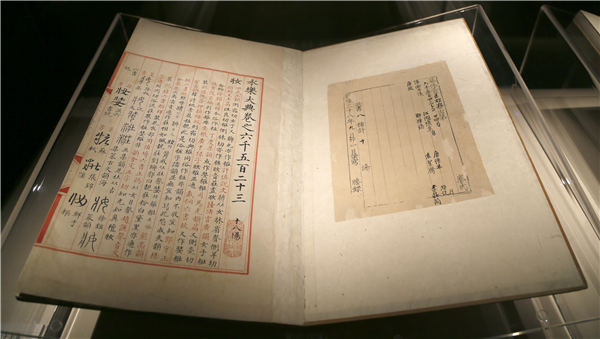

An exhibition at the National Museum of Classic Books in Beijing unveils the anecdotes behind The Great Canon of the Yongle Era. (Photo: China Daily)

A recent exhibition at the National Museum of Classic Books in Beijing brought to light anecdotes on how the Yongle Dadian was assembled, preserved, copied and then disappeared, and conjecture about the whereabouts of the original.

Twelve volumes, together with rare historical documents, rubbings, manuscripts, archives and photocopies of the canon published in different periods and collected overseas were on display.

The volumes are from the collection of the National Library of China, which is now home to 224 volumes - more than half of those in existence. 62 volumes are kept at the Taipei Palace Museum.

The canon was a compilation of ancient Chinese documents that included books - possibly as many as 8,000, written between the pre-Qin days (before 221 BC) to the early Ming Dynasty. The books include literary classics, astronomy, geography, medicine, divination, theater, crafts and agriculture, to name a few.

The canon was abundant with material from the Song (960-1279) and Yuan (1271-1368) Dynasties.

Each volume stands over 1.5 meters tall and is 1 meter wide, and typically include two rolls.

Stencil tissue paper and ink stick produced in Huizhou, now in Anhui Province, were used and considered best for handwriting.

Many of the blank spaces in the existing volumes were cut out for private use or imitating scripture paper, causing severe damage to the manuscripts.

Rather than a compendium of ancient books, the canon was arranged like a dictionary. The documents were distributed by paragraph or by passage, rearranged, and attached to different entries.

Each entry started with a Chinese character, followed by materials related to the character.

It has also provided an argument that the Venetian merchant and traveler Marco Polo (1254-1324) did indeed visit China, something that is a matter of dispute, says Yang Yinmin, a research librarian at the National Library of China.

One of the 60 transcript volumes that were turned over to the National Library of China in 1912 with the help of renowned intellectual Lu Xun. (Photo: China Daily)

The officer in charge of the compilation, Xie Jin (1369-1415), was known as "the most talented man in the Ming Dynasty" for his broad knowledge, strong discernment, unparalleled patience and thought.

In 1403, Xie gathered 147 scholars for the project. One year later, they turned in a first draft. But Yongle thought it wasn’t enough.

He later designated Yao Guangxiao to oversee the project, mobilizing more than 2,000 intellectuals, many of whom had exquisite handwriting.

Upon its completion in 1408, the emperor was so delighted he wrote a preface to it and named the work “The Great Canon of the Yongle Era.”

However, few of his successors took much interest in the canon until Emperor Jiajing, who frequently had several volumes at hand and often cited it in court.

When the Forbidden City caught fire in 1557, Jiajing was so concerned about its fate that he issued decrees calling for it to be saved.

In 1562, Emperor Jiajing decided to have the canon transcribed. Over 100 scholars were enlisted, including Zhang Juzheng, a reformer and one of the most famous prime ministers of the dynasty.

It took five years to complete the task.

One month after Jiajing passed away, his successor announced the transcript was complete, and it seems from that point on the original disappeared without a trace.

Four years before Emperor Jiajing died he urged a courtier to speed up the transcript and is said to have emphasized that the two versions would be kept in separate places.

Luan Guiming, a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing said the canon was buried with the emperor in the Yongling tomb in Northwestern Beijing.

In the 1990s, it was proposed that a high-precision gravimeter be used to search for a possible underground palace at the Yongling tomb.

However, the proposal was denied because archaeological and preservation technology during this time was not adequate enough.

Some experts have said the Yongling tomb is waterlogged, so even if the canon were there, it may not have survived.

Thanks to digitization efforts, the ancient encyclopedia can be preserved.

"These documents will be the window for people from all walks of life to understand and study the history of China. Only in this way can we make these precious ancient books live," said researcher and preservationist Liu Bo.

(Produced by Nancy Yan Xu, Lance Crayon, Brian Lowe, and Da Hang. Music by: bensound.com. Text from Global Times and China Daily.)