An anonymous mother and her daughter walk down a dirt road in a rural village in Hainan Province. (Photo: VCG)

○ The death of a 3-year-old girl throws her family into the whirl of internet violence

○ Fight over sick girl's medical treatment reveals clashing views in China's urban and rural areas

A recent interview video that shows a rural mother reflecting on the last moments of her 3-year-old daughter, who died from a possibly curable eye tumor, sparked a wave of apologies from Chinese netizens who regretted that they had previously criticized her after being misled by false reports.

Yang Meiqin, the 31-year-old mother of five children (four daughters and a son) from a village in Henan Province, who lost Wang Fengya, her fourth child, one month ago, was cursed by netizens as a "malevolent mother" over the past week.The whole process of Wang's treatment was exposed online, including Yang's fundraising and the failed treatment. Following Wang's death, several we-media outlets accused Yang of spending 150,000 yuan ($23,900), raised on online funding platform shuidichou.com specifically for Wang's treatment, on the girl's brother, who had a cleft lip.

Meanwhile, they claimed, Wang was left untreated and waiting to die because Yang favors boys over girls.

But few questioned the rumor or attempted to make further investigations into the details before they joined the chorus, hating and cursing Yang.

The news outlets later were proven to have twisted the facts, only after the local police intervened. But many netizens and volunteers remain baffled as to why Yang used the money to buy clothes, milk powder, toys and diapers for Wang instead of actively seeking medical treatment?

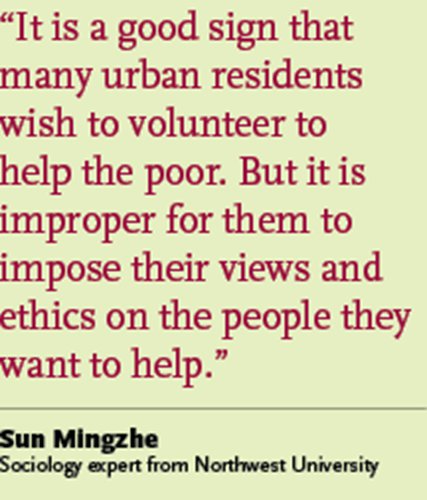

"They [People from the urban area] live in a totally different world from Yang and have a developed view about life based on urban ethics. They live peacefully separate. But when they tried to impose their views on Yang's family, clashes emerged," noted Sun Mingzhe, a sociology expert from Northwest University.

Wang Fengya holds her medical files. (Photo: Screenshot of a video by Beijing News)

Surrendering to life

Born into an impoverished family, Yang quit school at the age of 8 to learn acrobatics to earn money to improve her family's situation. She later married a man who she found out afterward is mentally handicapped and unable to support them. To earn a living, Yang performed wire-walking stunts while pregnant until her belly was too big.

Before Wang's eye problem was discovered, her younger brother, Yang's only son, was diagnosed with a cleft lip. Fortunately, the son received a free operation in April 2017 from the NGO Smile Angel Foundation.

Six months later, Wang was diagnosed with an eye tumor. Yang brought Wang, who did not have any medical insurance and thus could not get her bills reimbursed, to a hospital in Zhengzhou, Henan Province, in early November. A doctor told them that Wang needed chemical therapy, but Yang had to pay a 20,000-yuan deposit first.

She flinched at the deposit and the anticipated cost of treatment. After Wang was born, She became a full-time housewife without any income and relied on growing crops. Her husband, a safety guard in the city, earned only 2,000 yuan per month.

Without sufficient knowledge about cancer and therapy, Yang believed that cancer could not be cured; nobody in her village who had caught cancer had ever managed to survive. She worried the money would be wasted.

As the doctor later responded to media, given the uncertainty of medical science, they could not give a firm answer to Wang's family as to whether she could be cured.

"With limited knowledge, many living in rural areas think cancer is incurable; they are not confident that the treatment will work," Li Yafei, a doctor working in a hospital in Zhengzhou, told the Global Times.

Li went on to explain that, while it is easy for most urban people to understand terms like cure rate and five-year survival rate, for many living in rural areas, their understanding of a disease is black-and-white: curable or incurable.

"But for such a disease, it is hard to say absolutely whether it is curable," said Li. "In this situation, for a family with a low income, they must worry about the worst outcome: losing both their money and the girl's life."

Raising funds

As media reports show, Wang's family basically gave up seeking treatment after they left Zhengzhou.

Over the course of the next five months after they left the hospital, Yang tried twice on shuidichou.com. The first time, Yang raised about 12,000 yuan, mostly from friends and relatives. However, that money went toward paying for milk powder, toys and other daily necessities.

Meanwhile, Yang posted pictures and live videos on huoshan.com, a video platform, to earn more money. With the 2,900 yuan she earned this way, she took Wang to a hospital in her county for an examination in March.

The doctor there told her that the cancer had expanded to Wang's brain; he suggested she go to a bigger hospital. But Yang believed that Wang was "beyond cure," as quoted by Guangzhou-based Southern Weekly, and did not follow the doctor's advice.

But Yang still launched another fund-raising campaign several days later on shuidichou.com, explaining that the money would be used for Wang's "conservative treatment," namely intravenous drips.

This time, many volunteers began to question Yang's purpose. She was accused by some as a fraud. Some netizens including internet celebrities accused Wang of preferring boys over girls, which conforms to their stereotyped impression of rural people.

They pushed Yang to follow their advice to go to big hospitals, with some threatening to report her to the police, but Yang still refused.

"I felt I could not make it," she cried to dxy.com, a medical service platform in China. She stopped the crowd-sourcing campaign after hitting 23,116 yuan, and withdrew the money on March 27 to buy Wang some clothes and toys, as reported.

Then two volunteers from an NGO in Beijing later showed up at Yang's doorsteps one day promising to arrange Wang's treatment entirely for free. They were received with the utmost trust from Wang's family. However, conflicts soon emerged after Wang was taken to Beijing Children's Hospital in early April.

Just as Wang was closest as she ever had been to possibly being cured, Yang and the two volunteers came to a disagreement. Yang and Wang returned to their hometown.

When two other volunteers, from Shanghai, went to Wang's home several days later, the family was no longer cooperative, tired of these do-gooders' ever-changing promises and schedules. The family even lied that Wang had died, in an attempt to get rid of the pushy volunteers.

On April 11, township officials escorted Wang to the First Affiliated Hospital of Zhengzhou University. When a doctor there indicated that Wang needed to go to ICU and asked Yang to make a decision, Yang refused, saying she wanted to spend as much personal time with Wang as possible.

Until she died on May 4, Wang spent her last days on a bed in a small-town clinic, feverish and hooked up to pointless intravenous drips.

Two parallel worlds

Even though Wang's family and the volunteers hoped for the best for the little girl, they could not develop a proper dialogue given their different social backgrounds, educations and life views.

"It is a good sign that many urban residents wish to volunteer to help the poor. But it is improper for them to impose their views and ethics on the people they want to help," said Sun.

He called for more respect from charitable NGOs and hopes there will be more capable and reliable organizations that can fix the problems in their way without having to involve people like Yang in making hard ethical decisions.

"There is consensus about a child's rights in cities and for a disease with high cure rate, people usually try their best. But it remains hard to reach this consensus at the bottom of society," said Sun. "It depends on improving medical services, education and social welfare in rural areas to allow impoverished families to stand at the same level."

In places where medical resources are relatively limited, illnesses can drag a family into poverty. It is not considered so unpardonable for a rural family to give up the treatment of one sick family member in order to spare the others the burden of debt.

In the case of Wang, what urban residents see as violating a child's right to life was just one of the many life choices people like Yang must face every day. Indeed, a survey made by Xinhua a few years ago showed that, among the children who died of disease in China's rural areas, half failed to receive proper treatment before dying.

"The key to improving this situation might still be enhancing balanced development in rural areas, which are starved of suitable medical and education resources," noted Li.