For a decade, Xie Jincheng has been immersed in his duties at the National Library of China in Beijing. When asked how old he was, the 37-year-old had to pause for a few seconds to remember.

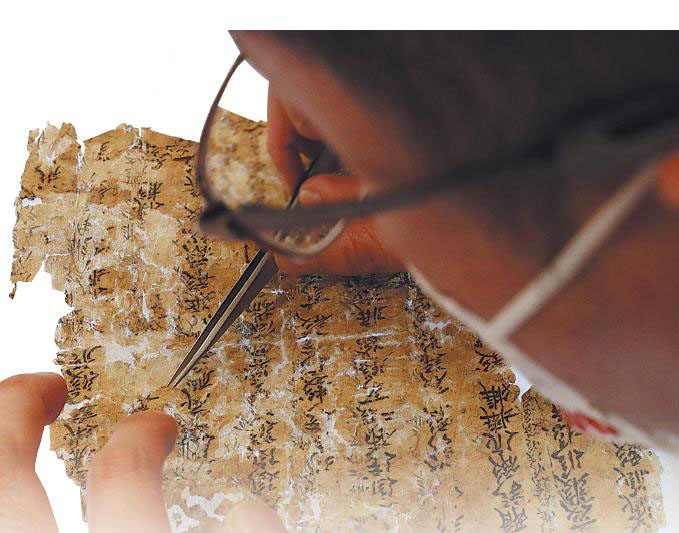

Xie Jincheng works on a document in Tangut, an extinct language from West China that dates back 800 years. (Photo: China Daily)

Each working day, he sits at a desk and focuses on handling ragged yet priceless pieces of paper in front of him. As one of 17 restorers of ancient books at the NLC, he shakes off centuries of old dust to renew the works he deals with.

Xie does not require a large space to utilize his skills. Using glue, scissors, tweezers, brushes and several other simple implements, he deftly restores the pages in front of him.

"I can basically handle most situations when fixing books, but you always have to be prepared for new problems," he said.

It is estimated that the NLC houses more than 3 million ancient Chinese books. The world's biggest collection of its kind, it comprises about 10 percent of such books in the nation. In China, the term "ancient books" refers to works predating 1911, the end of the Chinese monarchy.

Xie, who majored in chemistry at college, switched to cultural relics conservation at graduate school, realizing that there was a shortage of restorers of ancient books in China. Despite his multidisciplinary educational background, he thought that practicing a traditional craft was the best way to improve his skills.

It took Xie more than two years of observing his tutors and honing his talent before he was formally assigned to restore his first page.

Everyone working in this industry has to learn a saying from the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) book Zhuanghuangzhi: "Restoration (of books) is like seeing a doctor. If the doctor is good, your illness will disappear immediately following treatment. But if not, you may die taking the medicine. So if you cannot see a good craftsman, you'd better keep your item as it is."

Xie's given name can be compared to the approach he adopts to his work, as jincheng means "to be cautious and sincere". To ensure quality, he only restores a few pages a day, and if the damage is severe, it sometimes takes him several days to fix a single page. It takes much longer to search for the right paper to restore books, based on their original material.

"Sometimes it's impossible to get identical paper, so we need to process this ourselves," Xie said.

Precious herbal medicines and black tea leaves are placed on the workshop floor, providing a beneficial aroma. Dyed in yellow, the paper not only takes on its former appearance, but pesky insects are kept at bay by the aroma.

"The additions I make are usually thinner and lighter in color than the original pages, enabling my restoration work to be easily recognized," Xie said.

He often finds earlier signs of restoration, and although his predecessors might have made some mistakes, the patches they placed on pages were often kept to retain historical information.

Xie feels he is much more fortunate than restorers in ancient times. A long-term exhibition of key books restored in recent years opened at the NLC last year. Some of the titles he worked on are on display, with his name highlighted on tags.

However, most of the time, Xie and his colleagues work quietly behind the scenes. Patience is required, especially as Xie is now in charge of restoring a series of documents in Tangut, an extinct language from West China that dates back 800 years.

Unlike his colleagues who sometimes read ancient books to relax during work, Xie does not understand the works he is restoring.

He said, "This job is OK, but who wouldn't get bored after doing the same work for years?

"But this is what I'm good at. I can hardly recall anyone on our team leaving their job at this library. Once you take up this work, it can mean a job for life."

Du Weisheng, 69, is testimony to such devotion, having worked as an ancient book restorer at the NLC since 1974.

"It's great to see younger people joining our team and choosing to stay. They have good educational backgrounds, a range of expertise, and thus bring a more scientific approach to restoration," Du said.

Zhang Zhiqing, deputy director of the NLC, said there were fewer than 100 full-time restorers of ancient books in China in 2007. To change this situation, the National Center for Preservation and Conservation of Ancient Books was established that year, followed by a series of nationwide projects to better care for ancient pages.

"When discussing ancient books, scholars used to mainly focus on their documentation value," said Zhang, also deputy director of the national center. "But many people do not realize that books are precious cultural relics as well, like bronzeware or porcelain. Ancient books record our lineage of civilization, and their value sometimes is incomparable to other cultural relics."

Zhang said there are now more than 1,000 professional restorers in China, and about 3.7 million pages of ancient books have been renewed since 2007. Over 10,000 conservators have been trained for some 2,000 venues housing ancient book collections nationwide.

In 2013, Du became a national-level inheritor of intangible cultural heritage on ancient book restoration, and a training center was established at the NLC to nurture more professional restorers. Led by the library, 30 more training centers were established nationwide to produce a younger generation of talent for the industry. Seven restorers at the NLC are listed as tutors in this program.

"To show respect, my apprentices call me 'master', but I would rather consider myself their teacher," Du said. "Masters in ancient times were unwilling to pass down all their skills to apprentices, but as a teacher, I want these young people to surpass me."

The NLC is now home to some of the country's best-known literary treasures.

For example, 16,000 Dunhuang manuscripts dating to the Tang Dynasty (618-907), which were found in one of the Mogao Caves in Gansu province in 1900, are crucial witnesses to frequent cultural communication along the ancient Silk Road. They include the Yongle Dadian, which was the world's largest paper-based general encyclopedia and was edited following an edict from a Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) emperor in the early 15th century.

Some special collections are difficult for the public to understand, but they bear early signs of ancient Chinese civilization that have been passed on to the present day.

Inscriptions on oracle bones from the Shang Dynasty (c. 16th-11th century BC) are the earliest-known Chinese characters. These bones are mainly turtle shell and ox scapula, or shoulder blade, and the inscriptions were primarily used for records or telling fortunes. Today's Chinese writing system is the result of the continuous evolution of these characters.

There are 35,651 oracle bone fragments at the NLC-the biggest collection in the world. In 2017, the inscriptions were listed in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register program.

Yuan Yuhong retired from the NLC this year, but the librarian occasionally returns to the venue for an oracle bones exhibition, when she demonstrates how ink rubbings of these fragments are taken.

"The fragments are deeply rooted in my life. The skill has passed from one generation to another, and I'm a third-generation practitioner at the library. I miss making the rubbings," Yuan said.

In China, ink rubbing is a traditional method used to reproduce characters from stele inscriptions or stone carvings. Practitioners place pieces of paper on the surface and then rub the paper to obtain an impression. In this way, many precious works of calligraphy survive even after the original stones disappear over time.

Rubbing oracle bones is more challenging work though, as Yuan points out, due to different-sized bones and characters. Many inscriptions are also too small to be read.

In the 1960s, the NLC launched a system to enable ink rubbings of oracle bones, aimed at replicating the earliest characters. Yuan joined the library in 1986, but never expected to remain there for decades.

"In the first year, I was not allowed to touch the bones. I fully understood this requirement. Once a drop of ink oozed through the paper, it would damage the precious oracle bones. Our duty was to protect them, but if we made a mistake, it would result in damage," Yuan said.

She practiced rubbings on various materials until being allowed to touch some makeshift bones as a final rehearsal, which took several more months.

"I had to find the right degree of strength to use. After all, bones are not as hard as stone," Yuan said.

Thanks to years of practice, every step required to make rubbings became instinctive for Yuan. Due to her efforts, rubbings from all oracle bones at the NLC have been completed. She has also cataloged the bones.

Although her efforts over the years have greatly helped scholars' research, Yuan still has her concerns, as there are now no more oracle bones at the library available for the younger generation of librarians to replicate.

"However, I'm sure there will be new ways to pass down this skill to the public," she said, while demonstrating her expertise at the exhibition.

This year, the rubbing of oracle bones was listed as an intangible cultural heritage of Beijing-the ideal retirement gift for Yuan.

The work of some 300 employees at the NLC now involves ancient books, according to Zhang, the deputy director.

"These employees are not only conservators. Cooperation among the publishing, academic studies and digitization departments has taken ancient books to a new era," he said.

No matter how careful the librarians are, these books are still too fragile to be widely read by the public. No titles can be taken home by readers, according to NLC policy, but fast-growing digitization provides an alternative.

In 2016, a national-level database for ancient Chinese books went online for public use. Thanks to the National Center for Preservation and Conservation of Ancient Books, the online platform has expanded to 17 branch databases, based on different categories and including more than 100,000 ancient books nationwide.

For example, nearly 21,000 digitized copies of rare and precious editions of such books at the NLC are included on the platform. High-definition pictures of 3,764 oracle bones and more than 11,000 of their rubbings are also uploaded, as are 5,595 Dunhuang manuscripts.

The database also includes ancient Chinese books housed in overseas institutions such as Harvard-Yenching Library in the United States and the National Library of France.

"The public no longer has difficulty finding these ancient books, which can be accessed at any time," Zhang said.

Last month, the online database became available without the need to register.

According to the national center, in 2018, about 453,000 searches were recorded on the branch databases for "precious editions of ancient books", the most popular category on the platform, and the number of searches rose to 2.4 million in 2019.

Song Shangshang, who is studying for a doctorate in ancient Chinese history at Peking University, said about one-third of the historical files he cites in his thesis come from the NLC.

"For general readers, the price of published ancient books is too high," Song said. "Making these works freely accessible will greatly promote traditional Chinese culture, which used to be hidden in warehouses."

Yin Long, a program producer at audio-sharing platform Ximalaya, said that when he prepares a history course, he needs to double-check teachers' scripts by comparing various editions of an ancient book.

"Even though I'm off campus, I can still make full use of ancient books in our daily work (thanks to the database)," Yin said. "I really appreciate the national library's digitization efforts, which allow these cultural treasures to benefit more people."