Chang Jin, chief scientist of China's Dark Matter Particle Explorer (DAMPE) is often the first to finish a meal, a habit he developed as a child.

Chang Jin, chief scientist of China's Dark Matter Particle Explorer. (Photos: Xinhua)

In the 1970s, when US scientists observing the rotation of galaxies happened across an anomaly that suggested the existence of dark matter, Chang was still living at home in Taixing County in Jiangsu Province.

There was a lot of love but not much money in his childhood. He had three brothers, so at meal times whoever ate the slowest would eat the least. This meal time competition left him with another habit that continues to this day -- efficiency.

Chang remembers conversations with his dad about the expense of a project like DAMPE, "My father worried that if my work failed, the money wasted would be equivalent to the total income of tens of thousands of families in our hometown," said Chang. "That's why I work with extreme caution. We must succeed. We cannot waste the state's research money."

Chang has worked at the Purple Mountain Observatory in Nanjing, capital of Jiangsu, since 1992, and became DAMPE chief scientist in 2011. Back then, China was far from the space power it is today.

"I felt like I was working in a car factory where no cars were being produced," Chang said.

He would sit in the library for hours upon hours soaking up all he could about modern astronomical achievements, but they were all done in other countries.

In his early years at Purple Mountain, Chang and his tutor had developed an instrument that could observe solar flares and gamma-ray bursts. It was later installed on the Shenzhou-2 spacecraft and would collect China's first in-space astronomical observation data.

Chang Jin, chief scientist of China's Dark Matter Particle Explorer.

This was the start of a new era for astronomy in China.

China had a long way to go to achieve the sort of breakthroughs Chang had read about. But he saw an opportunity -- high-energy cosmic electrons and gamma-rays had still not been detected. Perhaps China could devise the detection method?

The observations from the Hubble telescope in 1998 changed the way we look at space. The expansion of the universe was speeding up, and this was likely caused by dark energy, and visible mass only accounted for a minuscule 5 percent of the universe -- the rest is dark matter and dark energy.

At that time, the equipment to observe high-energy electrons and gamma-rays was expensive and heavy. This pushed Chang to devise an observation method that used cheaper, lighter instruments that were already in use for other experiments.

US scientists were planning to release a balloon-borne instrument over Antarctica to observe cosmic rays. Chang proposed using that the very same instrument to detect high-energy electrons and gamma-rays. The US scientists were skeptical but eventually he persuaded them.

He flew to the US to write his idea into code, but calculating all the parameters was a huge undertaking -- and he didn't sleep for 36 hours but the results were worth it. One of the most important research papers from the program, later published in "Nature," named Chang as the first author.

During his research, Chang found an unexpected surplus of high-energy electrons. Had this been caused by the annihilation of dark matter? Had he glimpsed the "ghost" of the universe? A space probe was necessary for clearer observation.

Chang Jin, chief scientist of China's Dark Matter Particle Explorer.

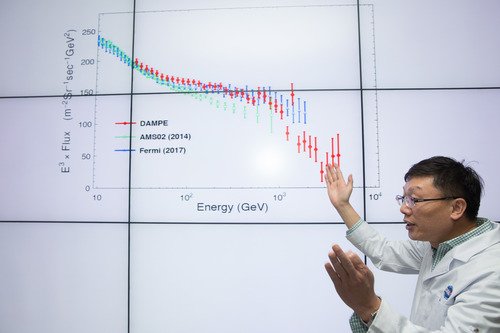

In 2011, China began to develop a series of scientific satellites including DAMPE. DAMPE cost just a seventh of NASA's Fermi Space Telescope and a twentieth of the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer (AMS-02), a state-of-the-art particle physics detector operating on the International Space Station (ISS).

Hundreds of scientists took part in the development. One of the greatest challenges was to improve how the satellite identified particles. Back on terra firma, this extremely precise method would be like identifying 20 specific people in a crowd of 20 million.

Another challenge was to extend the detector's dynamic range, equivalent to the human eye being able to focus on both a 2-meter-tall basketball player and a 2-micron cell on his body at the same time.

When DAMPE was launched on Dec. 17, 2015, Chang's reaction was muted. What if it didn't work?

Fast forward several months, and Chang saw a gamma-ray chart of the sky drawn by his team based on the DAMPE data. He couldn't hold back his tears.

"The chart showed the satellite was successful. It had honored the hard work of so many people," said Chang.

So far, the satellite has captured 4.7 billion high-energy cosmic ray particles, which could shine some light on the secrets of the universe. The initial findings were published in "Nature" at the end of 2017.

"DAMPE has opened a new window through which we can observe the universe, revealing new physical phenomena beyond our current understanding," Chang said. "I believe there are more surprises waiting for us."

(Source: Xinhua)