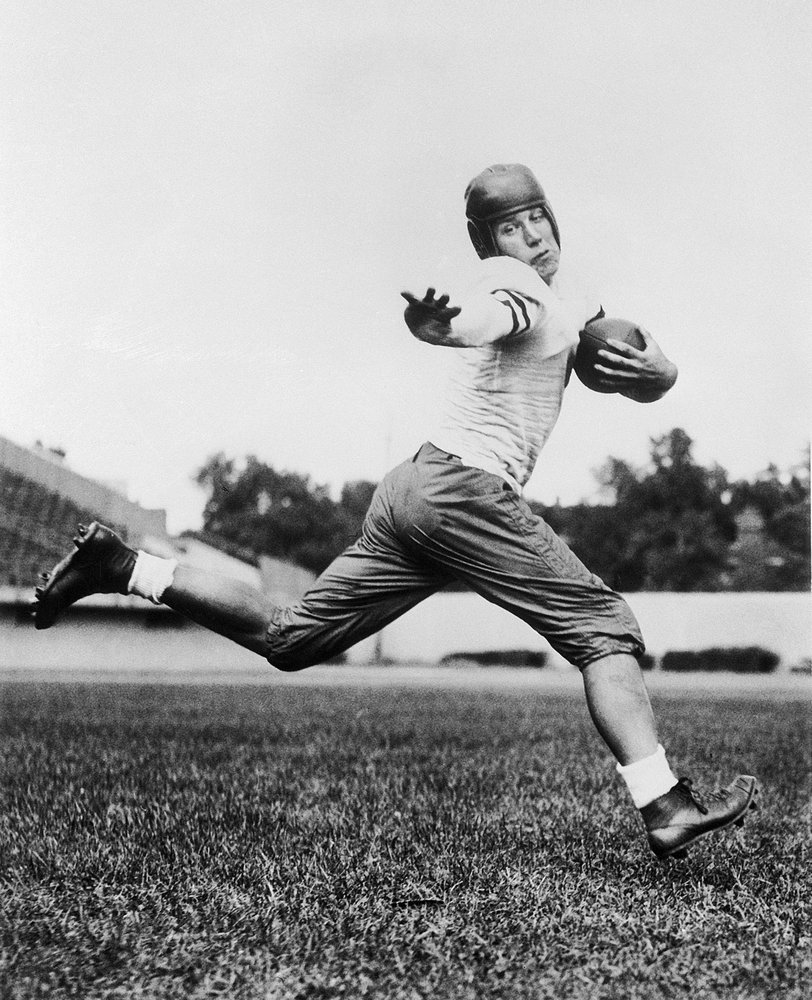

(Photo: AP)

Jay Berwanger won the inaugural Heisman Trophy in 1935 for the University of Chicago and became the No. 1 player taken in the first NFL draft a few months later.

He chose to work at a rubber company and be a part-time coach for his alma mater rather than try to make a living playing football.

More than five decades later, Oklahoma State Heisman Trophy winner Barry Sanders threatened to sue the NFL if it did not allow him to be drafted while he still had college eligibility.

In the early days of the NFL, college football was king and playing professionally was not something most players aspired to do. By planting its flag in large cities, embracing television exposure and playing a more entertaining style, the NFL surged in popularity in the middle of the 20th century and turned college football into a means to an end for many players.

Now college teams brag about sending players to the league, even while NCAA officials and college sports leaders try to downplay what has become obvious.

“I definitely think college football is sort of the minor leagues in a way. Like a breeding ground for the NFL,” said Eric Winston, who played 10 years in the NFL as an offensive lineman and is currently the president of the players’ association.

College football was already entrenched in American culture when the NFL was established in 1920 with most of its teams in small Midwestern towns.

“Baseball was the national pastime, but college football was the greatest sporting spectacle,” said Mike Oriard, a Notre Dame graduate and former NFL player who has written several books on the history of football.

Games matching Notre Dame and Army packed Yankee Stadium in New York in the 1920s and ’30s, even during the Great Depression. The Rose Bowl game was a yearly event on the West Coast on New Year’s Day. College football was seen as a worthy and noble enterprise: amateurs playing for school pride. The NFL was an abomination as far as the college football world was concerned,” Oriard said.

When University of Illinois star Red Grange joined the NFL in 1925, a deal scandalously planned while he was still playing in college, he drew scorn from those in college football. Not only was professional football considered barbarian, it was thought to be a lesser version of the sport. Indeed, the NFL champion played a yearly exhibition game in August against a team of college all-stars in Chicago, starting in 1934. The college players won six of the first 17 games and there were two ties.

Grange became one of America’s most famous sports stars, but he was more a phenomena than a trend setter.

“Professional football was out there as an option for former college players who didn’t have anything better to do,” Oriard said. “It was the Depression and if you didn’t get a job right out of college you might play pro football for a couple of years.”

After the league reorganized in the early 1930s and moved teams to big cities, it established a college draft. Berwanger was the first player selected, taken by the Philadelphia Eagles. His rights were later traded to the Chicago Bears. But the team never could meet his salary demands.

Davey O’Brien won the Heisman Trophy in 1938 and was the first winner to play in the NFL. He lasted two years before joining the FBI. That was typical throughout the 1940s and into the ’50s. Dick Kazmaier, a running back for Princeton, won the Heisman in 1951 and was drafted the by the Bears. He decided to go to Harvard business school.

Despite all that, the NFL was gaining traction among working-class fans in places such as New York, Chicago, Philadelphia and Cleveland that didn’t directly compete with college football. Salaries were growing and a career in football was becoming more appealing. College football viewed the NFL as the opposition and tried to keep it at a distance.

“Initially, when I came into the league in the late ’50s and especially with the Cowboys in the ’60s there were a lot of schools that did everything but ban you from their campus,” said Gil Brandt, the longtime Cowboys executive inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame last weekend.

College teams feared losing players with eligibility remaining to the NFL, Brandt said. He credits NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle and Cowboys owner Tex Schramm with assuring colleges the NFL would not take players into the league until their college careers were over.

In the 1960s, the emergence of the AFL brought competition for players and escalated salaries. While the college game was still mostly run-based, professional football teams were pushing the passing game. Joe Namath threw almost as many passes (340) in his first season with the New York Jets of the AFL than he did in his 30-game career (374) at Alabama.

“Eventually the NFL became so much more fun to watch,” Brandt said.

While the NCAA had rules in place that limited how often the top teams could appear on TV, fearing it would be a recruiting advantage and draw fans away from attending games, the NFL wanted as much television exposure as possible.

By the mid-1960s, top college football players were assumed to be heading to the NFL. It was clearly a step up in competition. The last time a college all-star team beat an NFL champion was 1963, a loss Green Bay Packers coach Vince Lombardi held over his players for years. The game was discontinued in 1976.

In the 1970s and ’80s, NFL strategies became more pervasive in college football, most notably in the increased reliance on the pass. As the two versions of the sport became more similar, college players were entering the NFL better prepared to play professional football.

The most significant development in the college-to-NFL pipeline in the 1980s came in 1989, when Sanders decided to jump from Oklahoma State to the NFL after a record-setting junior season in 1988.

The NFL said it was making an exception for Sanders, who was drafted No. 3 overall by the Detroit Lions and went on to a Hall of Fame career, but in reality it permanently opened the door to underclassmen. As NFL salaries soared, getting through college quickly became more desirable.

This year a record 135 players gave up college eligibility to enter the NFL draft once they were three years removed from high school graduation.

Meanwhile, as college sports come under attack by critics who believe players should get a larger cut of the billions of dollars generated by football, administrators would like to see more alternative paths to the NFL.

“Maybe in football and basketball, it would work better if more kids had a chance to go directly into the professional ranks. If they’re not comfortable and want to monetize, let the minor leagues flourish,” Big Ten Commissioner Jim Delany said in 2013. “I think we ought to work awful hard with the NFL and the NBA to create an opportunity for those folks.”

Six years later, in football, nothing has changed.

Big-time programs — not just the likes of Alabama, Clemson and Ohio State — want to be seen as a fast track to an NFL payday. They proudly display to recruits the names of former players who have moved on to the NFL on the walls of football facilities, in the pages of media guides and on social media.

Mike Lombardi, a former NFL executive who has worked for Al Davis, Bill Walsh and Bill Belichick, said the message from college coaches is: “You come here, you know we’ll develop you into a pro player. It sells that program.”