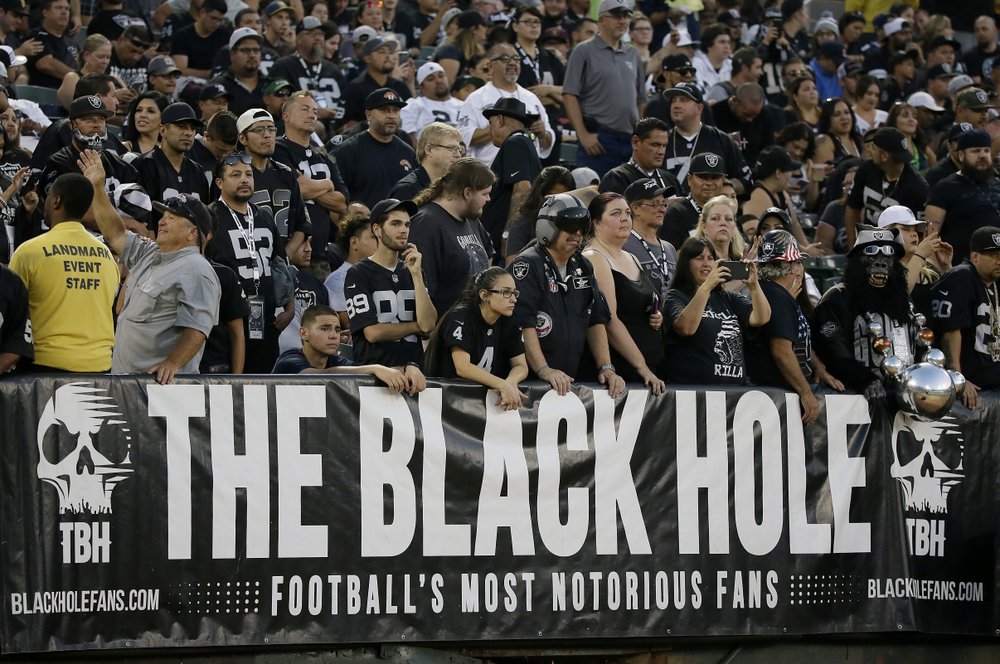

FILE - In this Aug. 31, 2017, file photo, Oakland Raiders fans watch from the Black Hole section of Oakland Alameda County Coliseum during the first half of an NFL preseason football game between the Raiders and the Seattle Seahawks in Oakland, Calif. (Photo: AP)

The slow, agonizing demise of the Oakland Raiders will continue for at least one more season.

There will be one more “final” home game at the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum, on Dec. 15 against the Jacksonville Jaguars.

There have been possible “final” home games for a few years now because the Raiders have had one foot out the door since 2015, when they joined with the AFC West rival Chargers in a failed attempt to build a stadium in the Los Angeles suburb of Carson.

This time, though, it almost certainly will be farewell for one of the NFL’s most recognizable teams and fan bases.

The Raiders are scheduled to move into a gleaming new $1.8 billion, 65,000-seat stadium in Las Vegas in 2020. The climate-controlled palace — funded in part with $750 million in public money — will make the Coliseum look like a relic.

It will be the second time the Raiders have moved since Chris Dobbins, 47, has been a fan.

This time, they won’t be back.

“Oh, it’s disastrous,” said Dobbins, an attorney who is co-founder and president of Save Oakland Sports. “In terms of twice in my lifetime when the team’s left, it’s very depressing.”

The Raiders have been the definition of lame ducks. Their move to Las Vegas was approved by the NFL in March 2017, but they’ve had to stay in Oakland until the new stadium is ready. They explored other options for this season, then agreed to a lease in Oakland for this year, plus an option for 2020 in case the Las Vegas stadium isn’t ready.

Fans know the end is near.

“This is the ultimate ‘Hard Knocks’ for Oakland Raider fans who have now lost their team for the second time,” said Andy Dolich, a long-time sports executive and Bay Area sports fan. He was referring to the HBO series that is featuring the Raiders this year.

Of course, relocations are nothing new in the NFL, which celebrates its 100th season this fall.

Some are quick, like the Baltimore Colts escaping to Indianapolis in Mayflower moving vans in the middle of the night.

Others are drawn out and painful. They tear at the fabric of communities and rip fan bases apart, with some swearing allegiance to their team no matter where it plays, while others stay loyal to the soil and cut ties for good. Bitter Twitter exchanges rage between fans angry about losing their teams and new fans who say the affected cities didn’t do enough to keep the NFL.

Many jilted fans swear off the NFL itself, saying the league cares more about money than them.

Once the Raiders are in Las Vegas, the recent wave of relocations of three teams will have affected five markets, with Los Angeles gaining two teams, St. Louis, San Diego and Oakland losing America’s most popular sport.

With the NFL looking to end its 22-year absence from Los Angeles — which had been a nice bargaining chip for owners elsewhere to wrangle new stadium deals to stay put — the Rams won the race for the nation’s second-largest city. Stan Kroenke, one of the league’s richest owners, dazzled his peers with plans for a nearly $5 billion stadium complex in Inglewood . The Rams were given approval in January 2016 to leave St. Louis and return to their former home.

The Chargers and Raiders were told to give it another try in their home markets. Both of those efforts failed, in large part because Californians are generally loathe to bestow public money on billionaire owners.

“Stadiums are the main story, much more so in the NFL than other leagues,” said Andrew Zimbalist, a professor of economics at Smith College in Massachusetts. “The reason people leave in football isn’t so much they want to go to a large demographic center, it’s because there’s a better stadium somewhere else. It’s purely a stadium-driven thing in the NFL.”

San Diego voters, weary of the Chargers’ 15-year effort to wrangle public money and/or land to build a new stadium, said no to Dean Spanos’ hastily written ballot measure in 2016 and lost its team of 56 years to Los Angeles, where the second-generation owner likely will benefit from Kroenke’s vision and deep pockets. Oakland city officials made it clear that public money would go to related infrastructure but not a stadium itself, and Mark Davis, another second-generation owner, found a sweetheart deal for the Raiders in bustling Las Vegas.

When the Chargers divorced themselves from San Diego in January 2017, fans flocked to their headquarters and dumped jerseys, pennants, caps and other gear into a large pile that was set afire. Others were more practical, giving team-branded clothing to agencies that help the homeless.

But even as the pile of singed memorabilia was scooped into a dumpster behind the Chargers’ headquarters, the team was handing out free jerseys and caps in Los Angeles in an attempt to build a new fan base. The Chargers will play a third and final season this fall at a suburban L.A. soccer stadium before becoming a tenant in Kroenke’s stadium.

The Rams, Raiders and Chargers have been involved in eight of the NFL’s 13 major moves since 1946.

The Rams moved from Cleveland to Los Angeles in 1946. In 1980, they stayed in the metropolitan area but vacated the Coliseum for Anaheim while keeping the Los Angeles name. With the Coliseum freed up on Sundays, Al Davis moved the Raiders there in 1982, and the next year they won the city’s only Super Bowl championship. After the 1994 season, the Rams bailed for St. Louis and the Raiders returned to Oakland, where they began play in 1960 as an original AFL team.

The Rams, unhappy with their stadium situation, left St. Louis for Hollywood before the 2016 season, making the Coliseum their temporary home. St. Louis also lost the Cardinals to Arizona in 1988, and the Cardinals originally were located in Chicago.

As for the Chargers, they began life in Los Angeles in 1960, also as an original AFL team, but their owner, hotelier Barron Hilton, was lured to San Diego in 1961. They rebranded as the Los Angeles Chargers in 2017.

Some cities that have lost teams have gotten new ones. Baltimore got what had been the Cleveland Browns, with Art Modell moving his team to Maryland in 1996 to become the Ravens while leaving the Browns name, colors and history behind. The new Browns began play in 1999.

The Houston Oilers moved to Tennessee in 1997 and eventually rebranded as the Titans. The expansion Houston Texans began play in 2002.

Based on the current economics and cost of stadiums, it would be surprising if the NFL ever returns to San Diego and Oakland.

The Raiders’ once-rabid fan base, which turned every autumn Sunday into Halloween with wild, elaborate costumes, hasn’t been the same since the move to Las Vegas was finalized, said Dobbins, whose term on the Coliseum Joint Powers Authority Board recently ended.

“Last year after it became a fait accompli, you didn’t see the passion that was there previously,” he said. “People are upset. The teams have been lousy, also. It was funny, when the Chargers were in town, it had been a big rivalry but the fans commiserated with each other. Rams fans and Chargers fans were upset about what transpired. Every game generates around 2,000 jobs, but it’s also hard to quantify when you lose a team, what it does to the fabric of the community. It’s very upsetting.”

Dobbins said he won’t attend games in Las Vegas, but knows fans who will.

Sin City, meanwhile, is getting ready to welcome the NFL.

Steve Hill, CEO of the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority, said it’s exciting watching the new stadium rising from the desert floor.

“It’s just great to see. Five years ago we wouldn’t have thought that was possible, and now it’s happening,” he said.

In San Diego, many fans have turned against the Chargers while some still cheer for them, or at least for quarterback Philip Rivers, who continues to live in the city while commuting north to practices and games.

Memo Garcia, 63, had been a Chargers fan since his dad first took him to a game at Balboa Stadium in 1963, back in the era of Hall of Famer Lance Alworth, Keith Lincoln and Paul Lowe.

When they moved, Garcia got rid of most of his Chargers gear except for a few jerseys, an AFL pennant and an aerial photo of Balboa Stadium. He even changed his Twitter handle to Formerly Boltmen and his address to @NoMasBolts.

“I was a fan of the San Diego Chargers,” he said. “To me there’s still an importance of where the team is from. They represented my turf. They don’t anymore.”

He’s largely sworn off the NFL. “I’ve got no dog in the hunt,” he said.

Johnny Abundez, known on Twitter as @JonE_Boltpride, said he’s still a Chargers fan, but not with the same passion as before.

“Phillip Rivers is still my QB! How can you not love him?” Abundez said.