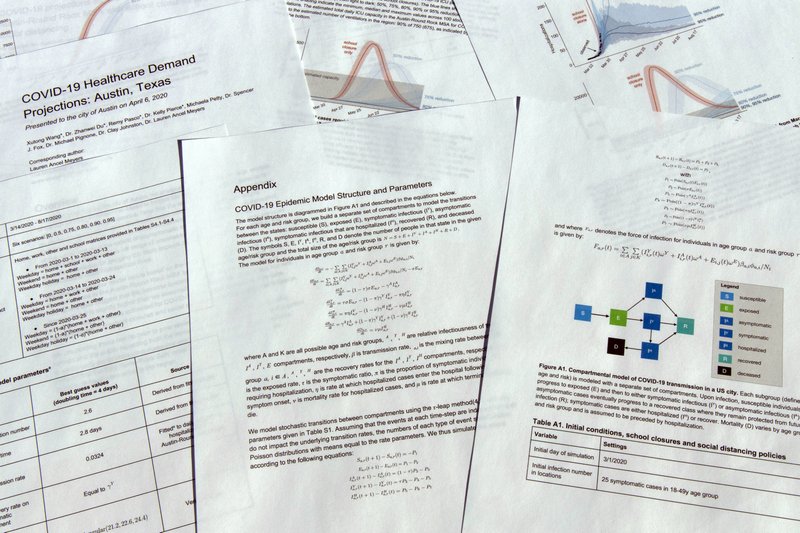

In this Monday, April 6, 2020, photo, a report delivered to the city of Austin, Texas, on COVID-19 health care demand is photographed in Frederick, Md. (Photo: AP)

State leaders are relying on a hodgepodge of statistical models with wide-ranging numbers to guide their paths through the deadly coronavirus emergency and make critical decisions, such as shutting down businesses and filling their inventory of medical supplies.

During hurricane season, coastal states can trust the same set of computer models to warn of a storm’s track. During this pandemic, there is no uniform consensus to predict the toll and direction of the virus that is tearing through communities around the country.

With little agreed-upon information, governors and local officials are basically creating do-it-yourself sources of information with their own officials and universities.

The models have resulted in conflict in several locations.

About 75 protesters on Thursday called on Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine to reopen businesses and questioned the models used by his health director to continue the state’s shelter-at-home order. Critics have denounced an Iowa Health Department a matrix as arbitrarily devised and being used by the governor to rationalize her decision to not issue a stay-at-home order.

The federal government and many states rely on a University of Washington model that’s the closest thing to a benchmark but it is so imprecise that the latest projection for the death toll had a range of more than 100,000. In Washington DC, health officials took the unusual step of publicly announcing that they didn’t trust the University of Washington’s updated model and embraced far more pessimistic predictions from a model created by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania.

Some states, including Alaska, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Minnesota, Louisiana, are incorporating the work of local researchers and other experts to fine-tune their models.

Some elected officials have cited the direst forecasts in issuing stay-at-home orders. Others have seized on more optimistic figures from their models to justify their calls to loosen restrictions.

“We know now that a lot of the models out there are not accurate,” Missouri Gov. Mike Parso said in describing why he waited until Monday to issue his stay-at-home order.

President Donald Trump’s handling of the pandemic could well decide whether he is reelected, and the models the White House relies on for forecasting will be an issue if they miss the mark.

Unlike with the National Hurricane Center, the federal government doesn’t have a national clearinghouse for virus models. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention hasn’t publicly released any coronavirus models of its own. The Trump administration favors the University of Washington model, but the CDC hasn’t identified a modeling consensus for states to follow.

Dr Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, said some public officials tend to act according to what “politically plays the best” instead of “following the science.”

“It’s good to have optimistic models, but I prefer to be more of a pessimist when you don’t know what’s going,” Benjamin said.

States worry about what models show because they believed there were more ventilators and other needed equipment stockpiled by the federal government than what actually exists, said Craig Fugate, who was head of the Federal Emergency Management Agency under President Barack Obama. Fugate said states are having difficulty planning and coping because the CDC, which is supposed to lead the pandemic response for the federal government, seems to be disappearing.

“When you do not hear from the CDC directly and you have all these other filters (of information), we’re losing the message,” Fugate told The Associated Press.

White House coronavirus task force members Drs. Deborah Birx and Anthony Fauci have delved into modeling at numerous briefings. Birx has said the task force has consulted a range of outside models to make the case for the need for social distancing to flatten the curve.

The federal government is trying to amass and process a trove of data on testing, disease levels, hospital capacity and other factors that could help improve modeling and maybe even focus down to the community level. It’s unclear how far the effort has gotten, particularly given all the other challenges that governments at all levels are facing dealing with the outbreak.

The model from the University of Washington, the one most frequently cited at White House press briefings, predicts daily deaths in the US have peaked and will decline through the summer. The updated model on Friday shows that 26,487 to 155,315 Americans will die in a first wave stretching into the summer. A few days earlier, the same model had projected up to 136,401 deaths.

Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards, a Democrat whose state has had one of the deadliest outbreaks of COVID-19, has said his administration is doing its own modeling. It’s a collaboration between the state health department, Louisiana State University, the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, a medical system and Blue Cross/Blue Shield.

Edwards called it “heartening” to see the University of Washington’s updated model forecasting a lower death toll. But he said, “the numbers in that particular model don’t match up so well with what we’ve already experienced, so we’re trying to reconcile the assumptions that underlie that model with the assumptions that underlie ours.”

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo has used his daily press briefings to explain how models have helped his administration forecast the pandemic’s impact on the Empire State. The Democrat has relied on projections from McKinsey & Company and Weill-Cornell medical center and consulted the World Health Organization.

But he has described the range of estimates as “maddening” and concedes that projections of an apex could change every day.

Natalie Dean, an assistant professor of biostatistics at the University of Florida’s College of Medicine, has seen an overreliance on modeling and confusion about the role it should play in responding to a pandemic. She said some of the most valuable information can be anecdotal, gleaned from people working on the front lines of the response.

“Models need to input parameters. You need to input a lot of assumptions about what you think is happening, and there’s still a lot we don’t know. We have to view numbers with skepticism,” said Dean, who is working with other experts on COVID-19 vaccine strategies.