Eight decades ago, in the rugged villages of eastern China, children with wooden rifles once stood proudly at checkpoints, greeting a tall, foreign man they affectionately called "Old Uncle Shippe."

Local women, weaving and chatting as they stitched shoes for soldiers, would pause to share their harvests with him—offering him precious white flour to make noodles, even as they themselves subsisted only on savory pancakes.

Hans Shippe wears a traditional Chinese straw hat in a counter-Japanese base area. (Photo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China)

He was Hans Shippe, the first Western journalist to enter the counter-Japanese base areas in East China's Shandong Province. In 1941, as Japanese forces launched a brutal sweep across Shandong, Shippe was urged by his comrades to leave for his own safety.

However, he firmly chose to stay, believing his mission was to resist the invaders by both reporting and fighting alongside the soldiers. During a desperate attempt to break through enemy lines, Shippe was gravely wounded and ultimately gave his life on the battlefield.

European origins and a revolutionary calling

Long before his final days alongside Chinese soldiers in 1941, Shippe had already lived several lives. Born in Kraków (now in Poland) in 1897 and later joining the Communist Party of Germany, he wrote articles under the pen name Heinz Moller for newspapers in Germany, the UK, and the US.

But it was China that awakened something deeper. His first encounter came in 1925, during the May Thirtieth Movement in Shanghai. Witnessing the violent crackdown on Chinese workers and students, Shippe grew disillusioned with the ruling Nationalist government and began to turn his attention toward the counter-Japanese forces led by the Communist Party of China.

Photo of Hans Shippe (Photo: Xinhua)

By the late 1930s, Shippe had returned to China, driven by a singular purpose: to see for himself what resistance looked like from the front lines. In the spring of 1938, he traveled through dangerous terrain to reach Yan'an, Northwest China's Shannxi Province, the heart of the revolution.

There, he was received by Mao Zedong and other senior leaders, and spoke with soldiers, officials, and ordinary workers. In his reports, published in media outlets across the world, he condemned the brutal atrocities committed by the Japanese army and called on the international community to support the Chinese people in their just struggle.

When pen meets gun

After leaving Yan'an, Shippe journeyed deeper into the heart of the war, embedding himself with guerrilla forces in East China's Shandong Province. Shippe often joined the local resistance groups, helping mill grain or assisting with basic medical care for children.

As Japanese "mopping-up" campaigns intensified, the army's command posts had to shift constantly. Though the military offered him a horse to ease the journey, Shippe refused to ride it, insisting instead that the animal be used to carry supplies or wounded soldiers.

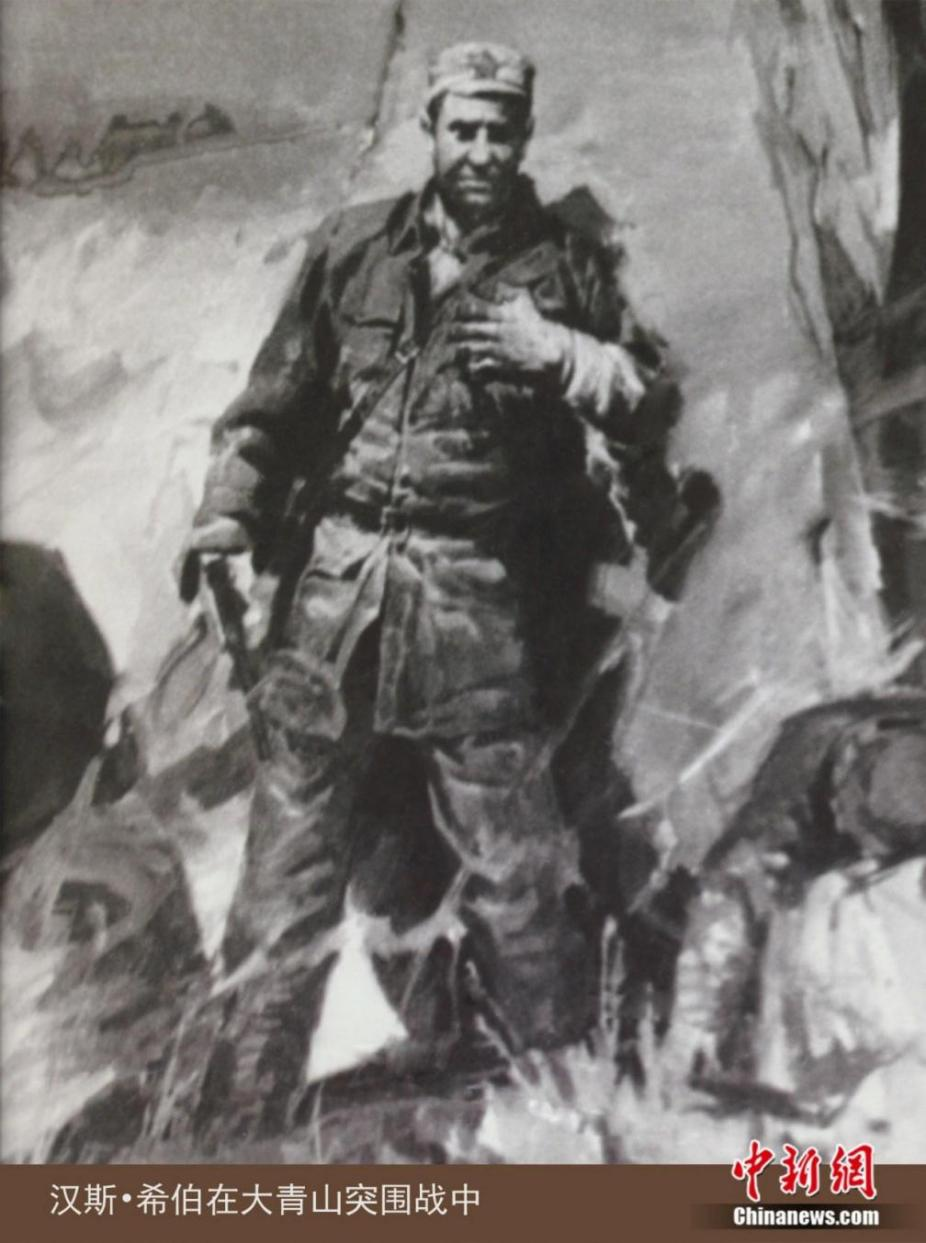

Hans Shippe during the breakout battle at Daqing Mountain in East China's Shandong Province, 1941 (Photo: China News Agency)

Shippe wore a cotton army jacket, carried a sidearm, and shared dry pancakes with soldiers around makeshift fires. Illness, blisters, and exhaustion never slowed him. Instead, he spent his days learning battlefield tactics, mapping terrain features, and speaking—through translators—with his comrades.

As the Japanese launched a large-scale encirclement of the base area, commanders again urged him to retreat to safety. But Shippe insisted on staying. To him, the pen and the gun were not opposing tools—they were both weapons in the fight for justice. In the end, he remained with the forces, determined to stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the soldiers.

Statue at the gravesite of Hans Shippe in East China's Shandong Province (Photo: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of China)

As a witness who chose to stand with the oppressed, Shippe document truth even at the cost of his own life. His story, like the very revolution he chronicled, is one not just of ideology, but of empathy—a reminder that some battles, though fought far from home, resonate deeply with the shared human pursuit of dignity and justice.