Medical workers in Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University in Wuhan, central China's Hubei Province, January 24, 2020. (Photo: Xinhua)

Imagine yourself in their shoes.

Imagine if you were a Chinese, living in China today, amid an epidemic whose death-toll has already surpassed that of SARS – and the number of reported infections is already five times as large.

Imagine how you'd worry about the health of your young child or elderly parent – the latter of which are the prime victims of this respiratory illness.

Imagine how neurotic, if not paranoid, you might become about touching door handles or elevator buttons or communal keyboards. Sure, wash your hands regularly and vigorously. But still.

Imagine how you might wonder if the person standing beside you could be a human incubator, even if outwardly asymptomatic. Or how your head might swivel if you hear a cough in your vicinity.

Imagine the trauma for the tens of thousands of Chinese already infected – plus the many thousands only suspected to be infected, but not yet confirmed. How they might dread that they'll die from this. And not just their individual trauma, but of their worried family and friends.

Imagine how you would demand that your government do something to protect you and your family. Now. Imagine if you were even in the shoes of a government leader: How would you respond?

Then imagine if you were Chinese, and you sense a global reaction that isn't an outpouring of sympathy and support, but an eruption of anti-Chinese racism and xenophobia. One that re-ignites the worst stereotypes about your people, which you hoped existed on the fringes, not in the mainstream.

Imagine if the world stitched a virtual scarlet-letter above your breast – whether you were just a visitor, or already living within their society – and branded you a menace to their health and family.

Sounds like tough times for the Chinese, no? But this isn't an essay on Chinese victimhood.

Because, as an American who's lived in Beijing since 2015 – and is now enduring the same anxieties of self-quarantine with some 1.4 billion Chinese – I hope my Chinese friends will also demonstrate a bit more understanding of how the world is reacting to this epidemic.

After all, empathy cuts both ways. If we want compassion for our plight, we should show compassion for what the other side is going through, too. Right?

So, my Chinese friends, let's imagine ourselves in the shoes of the international community.

Imagine if you were a foreigner, who's learning about this rapidly spreading virus, with mixed reports about its exact origins, about how serious the threat is, and how to protect yourself. And that you have an elderly parent or young child, whose health is among your greatest priorities.

Imagine you hear there's no cure yet for this virus, but that it's already much worse than SARS in 2003. Then, imagine you hear that both SARS and this Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia began in China.

Imagine your government and media have consistently, over the years, given you reason to fear China and its rise. Yet you've never been to China, don't know anyone who's lived there, or have any Chinese friends or colleagues who can "humanize" the Chinese – and explain a bit about their society.

Now imagine the daily drumbeat of news about this terrifying new epidemic, with nightmarish stories of quarantined cruise-ships, or how a single person can infect a group of others, like dominoes.

Yes, anti-China racism and xenophobia are real phenomena. They pre-existed this crisis, and the epidemic has now exacerbated both. But I've lived on four continents over the past 25 years. That's why I can state with confidence: It can't be that every incident we're now hearing about from around the world is being perpetrated by an actual "racist" or "xenophobe." Some, surely. But not all.

I understand the deep offense caused by such actions, but these are strong terms. And I sense some on this side are lobbing these accusations a little too loosely, especially if we ignore, without empathy, what are probably the two main root-causes of many incidents: fear and ignorance.

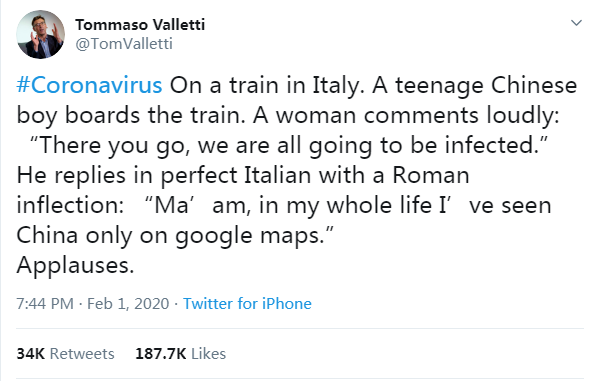

For example, I was struck by February 1st Twitter tweet, posted by an Italian economics professor:

Screenshot of the tweet.

On a train in Italy. A teenage Chinese boy boards the train. A woman comments loudly: "There you go, we are all going to be infected." He replies in perfect Italian with a Roman inflection: "Ma'am, in my whole life, I've seen China only on Google maps." Applause.

As of 10 days later, this tweet had collected 187,700 likes and 34,000 retweets. But two things about it: Is this evidence that proves this woman is a textbook racist and xenophobe? Maybe. Or was her cruel, stupid remark borne of fear and ignorance? Could be this could be that. Or, a combination.

What also caught my eye was the last word: Applause. Meaning, fellow passengers – whether they were Italians or immigrants, whether they were "pure" Italians or hyphenated Italians – supported the boy and his clever retort. So the majority supported the minority, against the offender?

That's cause for optimism. And at this crucial time, we in the media should do more to find and spotlight those abroad who oppose, even resist, racism, and xenophobia. They may be the silent majority – but the key to cross-cultural bridge-building. Moreover, for my Chinese friends, we should be cautious about not feeding the-world-is-against-us narrative; I question whether it's accurate, let alone healthy.

So, empathy can help explain the grassroots reaction. Then there's the governmental response.

Let's also imagine many millions of people across the West, and around the world, who are not only fearful and ignorant of the true risks posed by this new virus but how they would demand that their governments also do something to protect them.

Again, with empathy, imagine if you were a top official there: What would you do?

The reality is, these foreign authorities probably face a similar dilemma that the Chinese authorities here faced – or that any leadership would face anywhere when confronted with the potential for a looming disaster, whether natural or man-made. When do you sound the alarm? If you ring it too soon, you may cause needless panic. But if you wait longer – either to confirm the threat or to see if you can handle it more low-key – well, you may have waited a little too long.

From China, we can deem some of these steps, "over-reactions." Sure. But with a bit of empathy, we can also comprehend why at this particular time, many leaders would be willing to disregard nuance or subtly, and to err on the side of caution. As the saying goes, "Better safe than sorry."

Still not convinced? Here's one last if-you-were-in-their shoes scenario: Imagine how China itself might react if a lethal virus were emanating from America, or Europe, or Africa, or Southeast Asia. What actions would ordinary Chinese demand? Cancel flights? Shut borders? Target certain foreigners?

Through greater empathy from both sides, we can strengthen cross-cultural understanding.