On Monday afternoon, the British government asked people in the UK to stop going to pubs, clubs and restaurants with immediate effect. People are being asked to work from home if at all possible. Those over the age of 70 and with serious health conditions should self-isolate from this weekend.

Boris Johnson (C) meets with staff in a laboratory at the Public Health England National Infection Service in Colindale, north London. (Photo: AFP)

The United Kingdom is three weeks behind Italy on the curve, a far cry from the situation in France or Germany today yet heading inexorably towards that point. Even the European Union has demanded the closure of borders today, which would have been absolutely unthinkable a month ago.

The British government's control measures to slow the spread of the COVID-19 virus are less stringent than those of France, Germany or Italy. It believes that such measures are either not yet necessary, or not sustainable. They have offered advice to the public, requesting that they should voluntarily comply with these measures. Sir Patrick Vallance, the government's Chief Scientific Advisor, said that the measures are "not easy, but they are important and they will have the effect if we all do it."

The words "if we all do it" are important, but the government is using no legislation to enforce it. Instead, they hope that people will take their own decisions to change their actions and behavior.

I wondered what was happening in my city Sheffield, so – late at night, and on my own – I drove around the city center without leaving my vehicle. Pubs and clubs were not only still open, but there were queues to get in. I could see perhaps a hundred people gathered outside in a small area. Nobody was wearing a face mask. There would surely have been far more people inside, in an even more cramped environment. A few doors down the road, another pub looked equally busy. People were simply ignoring the government's insistence that they should maintain distance.

I felt disturbed and uneasy: simple mathematics would suggest that I'd probably seen someone who caught the virus completely unnecessarily tonight.

Restaurants are still taking new bookings for Sunday, which is Mother's Day here. People in China sacrificed their celebrations of the Chinese New Year whilst there were significantly fewer cases as the virus began to spread. It's perfectly reasonable to want to celebrate and thank mothers for the often-unsung work that they do throughout the year, but it's an understatement to point out that this does not require excessive risk or exposing more people to the novel coronavirus.

The United Kingdom is clearly reluctant to copy the aggressive containment actions of South Korea and China, fearing not only the social consequences but also that the virus could simply pop up again later.

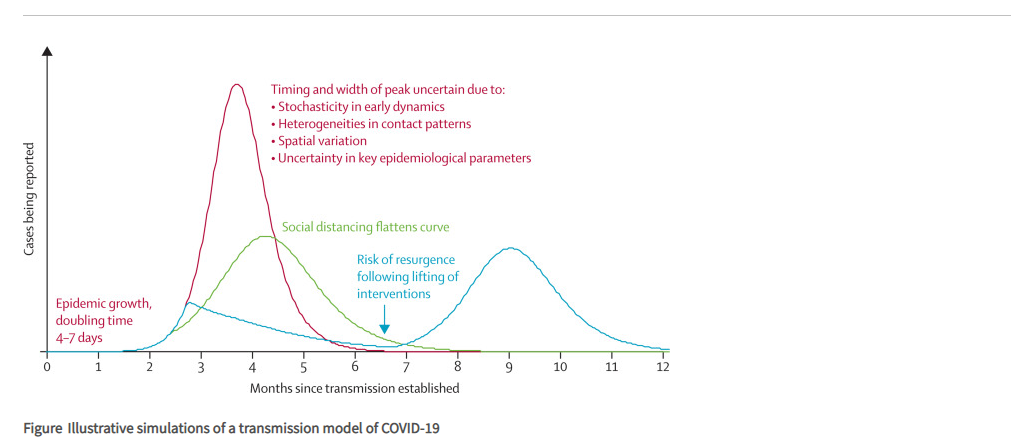

No doubt their mathematical models will already take into account a level of non-compliance with their recommendations. Members of Parliament from the ruling Conservative Party have been sharing an image across social media, in an attempt to explain the reasons why the United Kingdom's response is out of step with that in much of the rest of the world. In the long term, they argue, this will be better.

A screenshot of the chart published in The Lancet.

The chart is based upon an article in The Lancet medical journal. It argues that mitigation is better than full suppression in the long term. The scientific models behind the UK's approach are perfectly sound, but there is a difference between science and the correct public policy. Science should inform our approach, but there are plenty of variables which cannot be modeled. Government policy should be a combination of good science and a plan to react to circumstances as they change.

The UK's policy effectively assumes that a resurgence of the virus in those countries which suppress it is inevitable. In that case, the UK would indeed be better off by following this approach. Yet there's no guarantee that this will be the case.

As every day passes, scientists learn more about the virus. We know more now about which treatments work than we did. One of the many vaccines in development has already begun human trials, though it will take a long time to roll out internationally.

The United Kingdom itself believes that it is close to developing a new diagnostic test which will determine whether or not a person has already had COVID-19. This is a vital piece in the jigsaw because it should tell us what proportion of cases are asymptomatic and teach us how to avoid it.

Proponents of the British approach argue that it's a question of science versus ignorance. It's more complex than that: even scientists hold a complete variety of opinions on the subject, because there are too many as-yet unknown variables which cannot be modeled. The political decision is how to weigh up the risks of each course of action given possible future treatments and certain economic damage.

The British approach is a gamble: it presumes there's little if any chance of avoiding the worst-case scenario in which a huge percentage of the population eventually contracts the virus. It they're right, the United Kingdom will emerge in a relatively good position compared with other countries. If they're wrong, and if COVID-19 can be beaten as China's approach would suggest, then the UK's softly-softly approach will have led to unnecessary deaths. That is, ultimately, the benchmark against which they must be judged.