People tour the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the United States, Aug. 16, 2020. (Photo: Xinhua)

In April, my first COVID-19 report focused on the progression of the pandemic from China to Western Europe and the United States, and the belated mobilization and containment failure in Washington and Brussels.

My latest report – The Tragedy of More Missed Opportunities – focuses on the new missed COVID-19 opportunities and the consequent human costs and economic damage, particularly in emerging and developing countries.

At the current rate, the confirmed cases could exceed 25 million by the end of August. In the absence of deceleration, these cases could soar to 50-60 million and deaths to 1.5 to 1.7 million by year-end. And as projected in the April report, the devastation would prove most significant in the United States.

Trump administration's mismanagement

Through the pandemic, an uneasy coexistence has prevailed in the United States between the science-based health guidance of the nation's top experts and the politicized agenda of the Trump administration.

In a deeper sense, the pandemic failures began already in January 2017, when President Trump closed the National Security Council's global health unit, which had been created precisely to respond to global pandemics.

As of now, confirmed virus cases amount to 4.5 million, with over 170,000 deaths; new cases average over 65,000 daily. In the 1st quarter, U.S. GDP growth suffered a -5% contraction, followed by a historical, worst-ever -33% plunge.

The COVID-19 surge across America was to be expected in light of the catastrophic mishandling of the pandemic by the White House, as projected by The Tragedy of Missed Opportunities already in April. The consequent collateral damage in terms of public health and economic impact is likely to prove more protracted than currently expected.

And due to the central role of the U.S. in the global economy, that impact will have a negative "multiplier effect" on the world economy in the coming months.

U.S. epicenter – déjà vu

To understand the full magnitude of the adverse U.S. spillover, let's think of America's states as independent economies. By August, almost a fourth of the 25 most affected economies were in the U.S., with California, Florida, Texas and New York in the top-10, right after Brazil, India and Russia, and even South Africa.

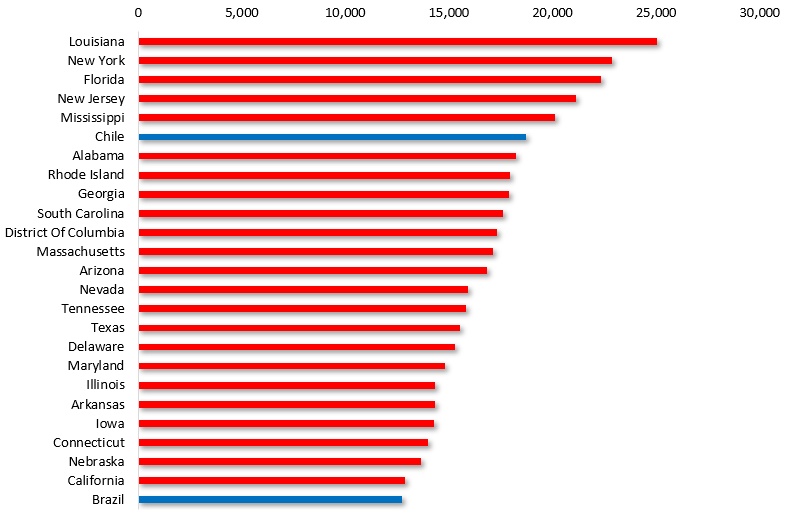

However, adjusted to the size of population, U.S. states accounted for a whopping 23 of the 25 most-virus affected major economies worldwide with Louisiana, New York, Florida, New Jersey and Mississippi leading the entire world, followed by Chile. Even populous Brazil (213 million people), which had the greatest number of confirmed cases after America, lagged behind U.S. states such as Iowa (3.2 million) and Connecticut (3.6 million).

Total confirmed cases / 1 million people by Aug. 1, 2020. Sources: Worldometer; Difference Group

When the U.S. eventually normalizes, associated resurgences of COVID-19 could prove likely in countries having close ties with the U.S.

While similar concerns also prevail in the Europe, Brussels has mobilized more effectively against the pandemic after March. And unlike the U.S., most European economies also have stronger health systems and/or universal healthcare which provides something a better cushion against the adverse public-health and economic collateral damage.

COVID-19 damage in the Americas

With weaker health care systems, the Americas offer a distressing demonstration effect. By late July, the geographic distribution of new cases – nearly half from the Americas – suggest the global pandemic had spread to the Americas, while adverse feedback effects were spilling over into the region.

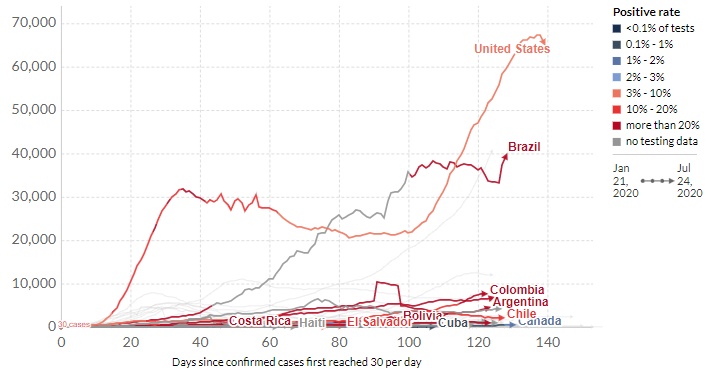

Daily confirmed COVID-19 cases, Jan 26 – Jul 24, 2020 (linear). Sources: European WHO, WEO/IMF database, Difference Group

Brazil identified its first virus case in January. Yet, numbers remained low until February, when new cases were linked with Lombardy, the epicenter of Italy's pandemic. By March, the number of infected members of the cabinet overtook Iran.

The Bolsonaro government initially ignored science-based evidence, shunned early mobilization and public-health imperatives. While most state governors did impose quarantines against the pandemic, by August Brazil had the second-highest number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in the world – over 2.6 million with nearly 70,000 new cases daily.

In the pandemic second-tier of Latin America, the key countries – Mexico, Peru, Chile, and Colombia – had each about 290,000 (Colombia) to over 415,000 (Mexico) cases by August. In Peru, the pandemic began with a youngmanreturning from travels in Southern and Central Europe in early March.

Afterwards, President Martin Vizcarra declared one of the earliest lockdowns in Latin America. Yet, prior to summer and despite a population of 32 million, Peru had only 1,000 intensive care unit (ICU) beds available in May (with 29 million people, Texas had 11,200 ICU beds).

Adjusted to population, Chile's pandemic has been one of the worst worldwide. Despite fewer than 20 million people and a high-income economy, Chile had over 355,000 cases by August.

In Mexico the first cases surfaced in late February with travel histories in Italy. On March 20, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo declared restrictions on travel across the Mexico-U.S. border. As local transmissions exceeded imported infections, pandemic accelerated.

Despite restrictions in Mexico to limit the inbound land-border crossings from the U.S., enforcement has been far more lenient. Meanwhile, the pandemic cases soared to nearly 420,000 with 46,000 deaths by August. Since early July, state governors in Northern Mexico have urged the central government to make it tougher for Americans to enter the country for non-essential reasons.

U.S. CDC warning: 'Difficult times in 2020/21'

The challenges in the Americas will not go away anytime soon and in the U.S. they could get worse, according to U.S. Centers for Disease Controland Prevention(CDC). In mid-July, CDC Director Robert Redfield sounded the alarm about the coming fall and winter seasons.

The confluence of flu season and the coronavirus pandemic is expected to make things challenging across America. "I am worried," Redfield said. "I do think the fall and the winter of 2020 and 2021 are going to be probably one of the most difficult times that we've experienced in American public health."

In the world economy, the pandemic exhibits significant regional differentiation, shaped by the anchor economies. In East, South and Southeast Asia, China's relative containment success prevented the early spread of the virus within the region. In Western Europe, failures of containment fostered the spread of the pandemic in Central and Eastern Europe, and regional proximity.

In the Americas, U.S. failures of containment and crisis management, coupled with poorer economies and weaker health systems in Latin America resulted in the worst regional crisis worldwide.

Yet, Canada's track record relative to the U.S. suggests precautions can work, despite elevated risks in the regional neighborhood.