Editor's note: James DeShaw Rae is a professor at California State University Sacramento and formerly a Fulbright Scholar at Beijing Foreign Studies University, 2017-18. The article reflects the author's opinion, and not necessarily the views of CGTN.

The notion of a "color revolution" developed over the past two decades as a concept to explain widespread anti-government protests in a variety of contexts around the world, particularly in the post-Soviet space. One may also ascribe the notion of color revolutions to the movements across the Middle East and North Africa in the early 2010s, collectively labeled the Arab Spring. In short, these were political movements seeking to overthrow the current government through mass public protest, emanating from a capital or major city sometimes throughout the nation.

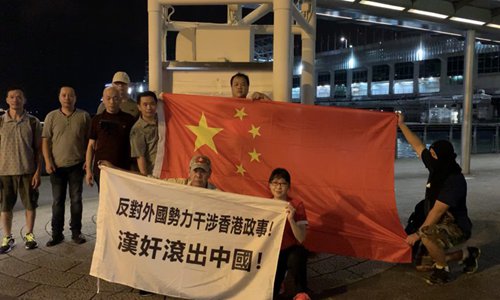

Patriotic Hong Kong residents pose for photos with the Chinese national flag at Hong Kong's Victoria Harbor on August 4. The banner reads "Opposing foreign forces' interference in Hong Kong affair! Traitors get out of China!" (Photo: GT)

The American scholar Lincoln Mitchell has explained some of the common characteristics of such popular movements in his 2012 book "The Color Revolutions." They typically result from questions over recent elections, include non-violent principles, organized political leaders play a major role, occur in weak states and international assistance is often pivotal in the outcome. Finally, his study of three such movements in Georgia (rose), Ukraine (orange), and Kyrgyzstan (Tulip) found them to be broadly unsuccessful in achieving lasting democratic change.

Is a color revolution taking place in China, emanating from the city of Hong Kong? Without a doubt, widespread protests occurred in 2014 and again this summer, mostly using non-violent principles, but have become more aggressive over time.

On June 21, protesters forcibly attacked and occupied police stations, and Hong Kong police have escalated their responses, along with forceful action by counter-protesters. Most recently, demonstrators have begun to occupy Hong Kong's vital international airport, attempting to bring the conflict to a head, while promoting strikes in public transportation that is grinding ordinary life in the city to a halt.

The situation is perilous and risks spiraling out of control owing to any number of factors. But is this a color revolution? Using the standards above, not exactly.

First, this movement is largely leaderless. Decisions appear to be driven primarily by largely disorganized youth who lack a realistic endgame and do not appear to have a clear platform and readiness to negotiate. Second, the amorphous group may not be able to maintain order in the ranks and follow a non-violent line, already disrupting public locations necessary for the common good and aggressively detaining or confronting police and suspected spies.

Violent protesters stain Chinese national emblem at the Liaison Office of the Central People's Government in the HKSAR, July 21, 2019. (Photo: CGTN)

Likewise, Hong Kong's unique democratic system created largely after the non-democratic British colonial government departed in 1997 has been a source of debate, but the reaction is primarily over the authority to extradite fugitives from Hong Kong to the Chinese mainland. Thus, the movement is unlike the national movements in other cases.

Most importantly, this movement is not occurring in a weak state; Hong Kong police are well-known for their professionalism, and China itself is not a weak state by any metric. Lastly, foreign assistance to the movement, including from the United States, in the form of guidance or inspiration may play a role but is unlikely to be pivotal; President Trump has suggested this is an internal problem to be resolved by Chinese authorities. Another aspect that is hugely impactful since the Arab Spring is the role of managing internal and external opinion through social media and traditional media.

Despite criticism, my experience during my many visits to Hong Kong and Macao is the striking upholding of the "One Country, Two Systems" model in both the political and economic realms. The rule of law, democratic accountability, freedom of speech, the right to peaceful assembly, as well as free trade, private property, transparent commercial relations, and clean management of the financial sector and good governance principles remain well preserved.

Beijing has been enormously restrained in its more than two decades of governing this very Chinese city. Little sympathy exists for the protesters around the Chinese mainland, and many such observers have access to foreign news outlets.

Why? Life in Hong Kong is good; core liberties have been maintained, and the entrepot remains a vital link in outgoing Chinese production and international investment into China. Culturally, the city is unique, owing to its mix of Eastern and Western values and norms.

All of these privileges have sustained since the return in 1997. Young people may romanticize the British occupation period, but flawless that time was not. Taking over the airport gains attention but is begging for a fight, one that can hopefully be avoided.

This movement shares one thing with the color revolutions; it will not be successful. Protesters gained the suspension of the disputed fugitive bill. Any expectations beyond that are unreasonable. Indeed, further escalation threatens to undo the "One Country, Two Systems" model as Hong Kong could be folded more directly under central government control.

Disputing China's sovereignty is a non-starter; the territorial integrity of China's political body is untouchable.