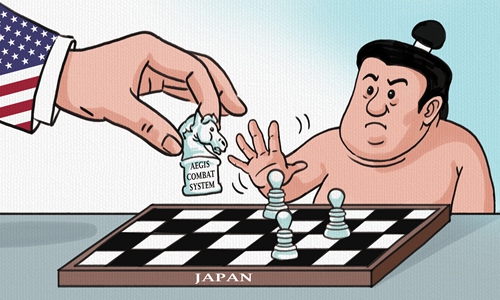

(Illustration: Global Times)

Japan confirmed on Thursday that it has effectively scrapped the deployment of the multibillion-dollar US Aegis Ashore anti-missile system, citing security concerns of local residents and the costly and time-consuming hardware upgrades as reasons for its decision.

For a country and government, the security of its citizens can be the biggest proclaimed reason for such a decision; however, it is believed that other factors may also be behind Japan's scrapping of its deal with the US.

Japan must have been aware that scrapping the deal would have major implications for its relations with the US. When Japan announced the program's "suspension" a few days ago, the US came to the table about it, and stated the country was looking into talking with Japan about its concerns. However, what's most troubling for the US is that the Aegis Ashore anti-missile system, including both the system's software and hardware, will be jointly developed by both the US and Japan; that is, if either side decides to scrap the deal, it will leave a mess for the other to clean up.

To fit out the anti-missile system, Japan also ordered the most advanced SPY-7 radar from the US Lockheed Martin Corporation, an American aerospace, defense, arms, security, and advanced technologies company. It also signed an equipment purchase deal with the US worth 180 billion yen ($1.6 billion), of which 20 billion yen has already been paid. The sudden scrap of the Aegis Ashore deal will bring huge losses to the US military and defense companies, and must also be troubling to the Trump administration, which has been unreserved in its selling of weapons to Japan.

Japan was not 100 percent willing to deploy the US missile defense system, and it is believed that the country was under pressure from the US to make the arms decision back in 2017. Regardless, Japan's recent announcement that it would scrap the deal by taking advantage of the current political chaos in the US shows that it wants to make its own diplomatic and defensive manoeuvres to display its independence and deploy its military freely in East Asia away from US hands. It's also entirely possible that the Abe administration does not expect Trump's re-election by the year's end, so he takes everything the current administration says with a grain of salt.

If we assess Japan's move simply from the defense system's point of view, we can say it favors China-Japan relations. In this case, Japan's next step is key. Without the US anti-missile system, how will Japan ensure its national security? The Nikkei Asian Review reported on June 25 that Japan will explore the development of its own pre-emptive--strike capabilities against foreign rocket launchers as a less-costly alternative to the Aegis Ashore missile shield, which actually tests international opinion.

Why? Japan's self-defense-only principle under the country's war-renouncing constitution, adopted in 1947, prohibits its military from making the first strike. By signalling that it will explore the development of its own pre-emptive-strike capabilities, the Japanese government is mulling for constitutional amendments that could send shockwaves across the world. Even during a pandemic, Abe has never given up this impulse to raise the issue of constitutional amendments; however, considering the current low support rate for his administration, Abe will expect criticism for such a move.

The future of Japan's peaceful constitution has significant implications for the China-Japan relationship. During his administration, Abe has often been tempted to exaggerate China's threat so as to justify his backhanded agenda. However, as bilateral relations have seen a sign of easing in the past two years, it is critical for China to observe Japan's alternate motives. If Japan deploys similar systems on islands adjacent to China or close to China's sovereign waters, it will definitely impact China-Japan relations.

The author is an associate research fellow at the Center for Japanese Studies, Fudan University.