Illustration: Liu Rui/GT (Photo: Global Times)

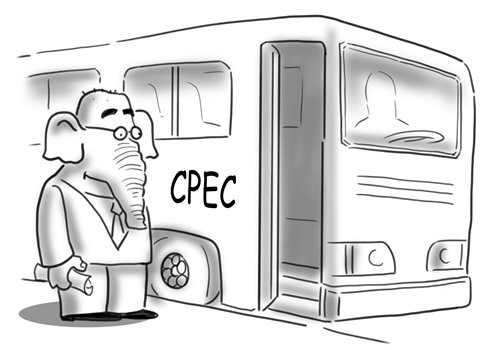

At first glance, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) appears a bilateral project between China and Pakistan. In reality, the corridor's optimum results could be achieved by linking it with regional countries: India in the east of Pakistan, and in the west Central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran and the Middle East. The present momentum indicates progress solely westward. Given the bitterness of India-Pakistan relations, Pakistan neither officially invited India to join nor did India show any interest in the corridor. New Delhi in fact opposed it.

Indian opposition comes from its alleged sovereignty issues. New Delhi claims that a part of the corridor passes from Pakistan-controlled Kashmir, Azad Kashmir, which India asserts is its own sovereign territory. In the Indian view, China and Pakistan have no right to develop the corridor.

This is not the first time China and Pakistan have developed projects in Kashmir. In the past they developed projects like the 1970s Karakoram Highway. Given the scale and the scope of the corridor, the Indian reaction is relatively strong. India needs to realize that its participation or opposition, and the development of Kashmir as a result of the corridor, will not affect the legal positions of India and Pakistan on Kashmir.

Secondly, if one supposes for a while that the corridor truly involves a disputed territory, then what about the Bangladesh, China, India, Myanmar Corridor launched earlier than CPEC and not passing through any disputed area? This corridor received a lukewarm response from India and so did not achieve any progress.

In fact, many Indian quarters view China-led projects with deep suspicion. They cannot break from the past and continue to view Sino-Indian relations from the prism of the 1960s. This mind-set led India to boycott the Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation where it missed the opportunity to interact with delegates from more than 60 countries. We assume that all of them had come to Beijing after careful consideration. Even India's close ally the US and Japan had representation.

It is India's legitimate right to decide whether or not to join the project. However, distancing itself from a 21st century project of unprecedented connectivity, economic opportunity and interdependence is worth a second thought if India aspires to big power status. To achieve its ambitions, India needs economic development which is entwined with the uninterrupted flow of energy and peaceful borders.

No doubt India is deepening ties with the oil-rich Gulf, the Middle East and Iran for energy security. Without the corridor and normalized relations with Pakistan, India must connect with these regions via long land and sea routes and so exponentially raise the cost of imports and exports. The cost-effective but now redundant Iran-Pakistan-India pipeline is one of the victims of India-Pakistan rivalry. The reality is that Pakistan is the key component in India's direct links with Afghanistan, Iran, Central Asia and part of the Middle East.

To be fair, India is not solely responsible for regional disharmony. Pakistan played its role too. Islamabad never invited India to join the corridor officially. Instead, Pakistani authorities accused India of sabotaging the project by fanning insurgency in Baluchistan. Islamabad ignored the fact that the exclusion of India, with the world's second largest population and an emerging economy, would be to its own disadvantage.

If the Pakistani elite think realistically, the country can work as a conduit to link energy-starved India with energy-rich regions and in return reap economic benefits and access for its own products to Indian and Southeast Asian markets.

This would develop interdependence, remove the prospects of Indian sabotage, ensure security and at a later stage, pave the way for dialogue: the only way to settle disputes. This long-term perspective is lacking among Pakistani strategists.

It might be difficult for India and Pakistan to think about a change in their nationalistic perspectives on Kashmir. To begin, they can devise a modus operandi that cooperation on the corridor will not affect their stance. Or at least India can join or be invited to participate where alleged sovereignty is not infringed.

Every cloud has a silver lining. Apart from public discourses, serious quarters in both India and Pakistan do explore possibilities of cooperation. An earliest realization is better.