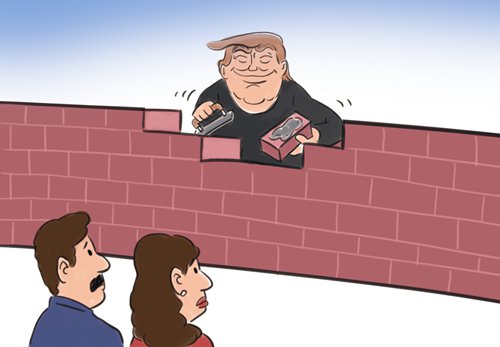

(Illustration: Global Times)

"Trade wars are good, and they are easily won," said US President Donald Trump upon embarking on his recent burst of tariff announcements, first on steel and aluminum, and then on a range of Chinese products. Measures targeting China's technology sector, most notably telecom giant ZTE, followed, banning it from acquiring US inputs for its cellphones, wreaking havoc in the global supply chains of one of the digital era's poster products and threatening the very survival of one of China's biggest high-tech companies. China, in turn, announced tariffs on US exports. In addition to high-value industrial products like passenger planes, SUVs, chemicals and plastics, they also included foodstuffs such as soy, grains, tobacco, pork and wine. The jury is still out as to whether they will be implemented, and if so, for how long, but their very announcement has already sent markets in a tailspin, and the fact that no bilateral talks on these differences have been held yet suggests we may be in for a longer haul than had originally been forecast.

A rules-based international trading system has been reduced to the spectacle of countries like Australia scrambling to deploy one of its professional golfers - an acquaintance of Trump - in an effort to have Australia exempted from the above-mentioned steel tariffs. Another close US ally, Japan, has been shocked to find out it would not be exempted from these tariffs either, affecting the credibility of Prime Minister Abe's government, one of whose biggest assets was precisely its supposedly close links with the current occupant of the White House. In damage-control mode, a hurried invitation to Mar-a-Lago was generated, to assuage hurt feelings in Tokyo.

Most economists would agree to the proposition that trade wars are neither good nor easy to win, and, although the first shots have been fired, there is still hope that an all-out trade war will be avoided. Hope springs eternal, they say. Yet the global trading system, already in serious difficulties - with international trade in goods growing at barely half the rate it did before the 2008-2009 financial crisis - is not being helped by this spat between the world's two biggest economies, that may easily degenerate into something much more serious, as ratcheted-up, tit-for-tat, protectionist measures often do.

What about the effects of all this on the rest of the world, and particularly on Latin America? Twenty years ago this would have been a non-issue, as trade between China and Latin America was almost non-existent. Ever since China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, though, this has changed. Sino-Latin America and Caribbean trade last year reached $266 billion and China is now the No.1 trading partner of Brazil, Chile, Peru and Uruguay, and the No.2 for many more in the region. Although much of Latin America's exports to China consist of mineral resources like oil, copper and iron ore, food exports have also been on the rise, from 20 per cent of Latin American exports to China in 2010 to 30 per cent in 2016. As it happens, these exports are also highly concentrated, both in terms of products, and of countries. Soybeans represent 72 percent of these exports, and Brazil, in turn, 70 percent of all of the region's exports to China. Four countries - Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Uruguay - represent 97 percent of these exports. One-fourth, $5 billion in fruit in 2016, comes from Chile. Three-fourths of all chicken meat imports hail from Brazil. Argentina and Uruguay export increasing amounts of beef. In fact, a little over one-fourth - 26 percent - of all Chinese agricultural imports now originate in Latin America.

The million-dollar question, then, is how will the incipient trade war between the US and China impact Latin America? Some see an opportunity for Latin American foodstuff producers to benefit considerably. After all, some US exports affected by tariffs will be priced out of the market, and Latin America should be able to move in swiftly and fill the gap. Brazilian soy producers lead the list of those most likely to do so. With Argentina having undergone a recent drought, it would be more difficult for its exporters. With California wines on the list, Chile - whose wines are already among the favorite of Chinese millennials, that have placed Chile as the third largest exporter of wine to China - has also interesting opportunities to increase its market above and beyond the $200 million it is already selling in China.

In terms of industrial products, some also see possibilities in China for flat screen television sets produced in Mexico, as well as for Brazilian passenger planes and plane parts from Brazil's Embraer. The broader point is that, although this increasingly acrimonious US-China dispute offers an opening for a range of Latin American products, this is not something automatic. The international market offers quite a few alternatives.

Warnings of US-China trade tensions came from Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross at the Summit of the Americas in Lima a few days ago and from former secretary of state Rex Tillerson in his speech at the University of Texas at Austin before his Latin American tour in February. They suggest that Latin American nations will have to brace themselves for a delicate balancing act in their foreign relations. To find the right equilibrium between traditional, long-established ties to the US and the fast-growing and ever-more dynamic ties with China will demand a high degree of diplomatic skill and regional and sub-regional coordination, so far sadly lacking.

The author is a public policy fellow at The Wilson Center in Washington DC, a non-resident senior fellow at the Center for China and Globalization in Beijing, and a former ambassador of Chile to China.