(Photo: Global Times)

Western societies have put their reputation in doubt and destabilized themselves, trying desperately to overcome their embarrassment by electing populist demagogues. How come the winners of the Cold War, the richest societies in history, lose bearing and orientation? The answer is not easy and does not lie in short-term "crises" - the problem has to be detected at a deeper level of historical and social evolution. Here is a proposal:

The first generation after World War II knew what to do: rebuild the world, regenerate the economy, grant survival, combat hunger, provide for basic goods like running water, food, housing; work for reconciliation among former enemies, against hatred and extremism, create structures for international communication and cooperation; the consciousness of the need for social coherence was common, it was only too obvious that the disaster the war had produced could not be overcome by individual effort, but only by a common enterprise.

This attitude, realized by existential experience, allowed for societies in Germany, France, the UK, Italy, but Japan and the US as well, to go for a joint and equitably shared effort, to launch what was later dubbed "the Golden Age of Capitalism," or - in the French version - the "Thirty Glorious Years." It was a balance, an equilibrium between individual freedom - the central Western value - and social commitment, a shared conviction that only together, in a largely just society, could the evils of the previous half century - when Europe went To Hell and Back (title of the best book on this era, by Ian Kershaw) - be overcome. And so they did: The Western (more European than American) welfare state and its societies provided a whole generation and their efforts with existential meaning: It was worthwhile to work and engage, to suffer and enjoy for that project.

The whole setting went into crisis in the 1970s, not so much because of external triggers (like the dollar crisis in 1971 or the oil price shocks in 1974 and 1978), but because the growth mantra was no longer sustainable - everybody had nearly everything now you could wish for: jobs, houses or flats, household equipment, communication (TVs) and mobility (individual cars) tools, paid holidays, etc.

What do you sell when everybody has everything?

Saturated markets were the problem. This slowed down economic growth and put into question the "ever more" promise of the previous generation, which had freed itself from its original meaning. The solution of the crisis of the 1970s was twofold, political and technological, neo-liberalism on the one hand (Reagan and Thatcher) and microchip revolution on the other. "Government is not the solution, government is the problem," said former US president Ronald Reagan, and former British prime minister Margaret Thatcher claimed that "there is no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and there are families."

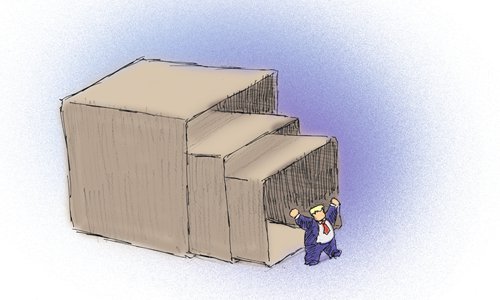

Everybody was now encouraged to go for his own, individual aims and goals, all individual energies were to be set free in order to reach the overarching goal, i.e. the revival of the lost growth rates of the "Golden Age," all obstacles on this way were to be abolished, social obligations in the first row. And the new devices built with microchips, i.e. personal computers, cell phones and many more applications, revived the economy by means of an industrial revolution with global impact. The second post-war generation was marked by the individual desire to accomplish one's own dream, by continuing the success story of the post-war era at any rate, at any cost - a ruthless quest for becoming richer and richer.

Still, the setting was meaningful to many, if not to all members of Western societies - the goal of unbroken growth could still be perceived as a "common good," worth investing your lifetime and energy in, and even to accept some inconveniences. But the price was high: Thatcher's dictum proved to become nearly a self-fulfilling prophecy - societies were split between winners and losers of that unlimited individual liberty, no longer bound by social responsibility, societies were dismembered, plagued by growing inequality.

The socio-democratic attempt to find a "third way," at the end of the century, proved to be inconclusive and contributed to the definite decline of Western social democracy. It only needed a trigger to reveal how fragile the Western model of development had become, and that trigger did not wait for a long time coming: The disaster of the financial sector and markets in 2008 made it obvious that the second post-war generation relied on shaky grounds, that its project was no longer an acceptable promise for a whole generation, a whole society; that its denial of responsibility for the profit of liberty, its denial of solidarity for the profit of the pursuit of individual "happiness" had undermined the fundamentals of social cohesion and put into question the wholesome meaning of human efforts in social communities.

Today, the West is facing the emergence of a third post-war generation. Its shape, its shared beliefs, its project is not yet clearly perceivable. The current situation is still marked by features of the perishing neo-liberal era, like individual, egoistic pursuit of interest, denial of responsibility, but without trust in the reliability and sustainability of such attitudes. Contemporary demagogues and populists - Donald Trump is an outstanding, but by far not the only example - exploit the uncertainties of many people, foment hatred and encourage the individual denial of truth ("fake news"), all obvious signs of a quest for a new approach, a new setting, as much as desperate, hysteric moves without a project, without direction, without future.

What the West is really suffering from is the lack of a project worth filling the life of a new generation with meaning and sense.