(Photo: Global Times)

US President Donald Trump finished the first two stops of his European tour after attending the NATO Summit in Brussels and paying a working visit to the UK in quite a fashion.

NATO allies were relieved to have got away without seeing the worst of the US president who was expected to upset the apple cart in the meeting. If Trump had refused to sign the joint declaration as he did during the G7 summit in Canada, it would have created fresh acrimony. This time, two declarations were signed by the US, including Brussels Summit Declaration and Brussels Declaration on Transatlantic Security and Solidarity. In both documents, NATO countries including the US reassure that their security alliance is still robust. The members commit themselves to tackling various security challenges and threats including Russia, terrorism and cyber crime.

Despite two declarations, Trump is concerned about the economic aspects of NATO and threatens to link US commitment and financial burden-sharing. He insists that US allies should spend more on defense and that NATO members should meet a pledge to spend at least 2 percent of GDP on defense. This time, Trump even asked for more, telling NATO leaders that they should increase their defense spending to 4 percent of GDP.

Trump's UK visit also showcases how his business mindset has dominated US policy toward Europe. The real estate tycoon started using his backing for Brexit as leverage to negotiate an FTA with the UK. He never cares whether the process of Brexit is smooth or not, but is only bothered about economic gains that the US can possibly make from Brexit and the FTA. For instance, US insists that the UK should follow many requirements as a condition for an FTA, even though this would severely limit London's capability to negotiate a trade deal with the remaining 27 EU members.

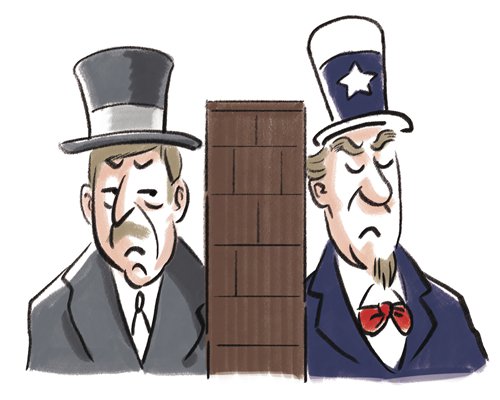

Under the slogan of "America First," Trump has jolted transatlantic relations, disregarding European interests and voices, and dismissing coordination with the continent in trade, security and international affairs. It seems that the US has gradually become a reluctant partner of Europe and perceives Europe as an economic competitor rather than a strategic ally. For the first time after World War II, the US' redefinition of Europe's identity pushes transatlantic relations to an inflection point.

In fact, the antagonism toward Europe hasn't come about suddenly. The significance of Europe in US global strategy has been systematically diminished since the advent of the 21st century. George W. Bush had considered to pivot strategic resources to Asia but was interrupted by the September 11 attacks in 2001 and had to invest more into the Middle East, helping Europe stabilize its larger periphery. With the slogan, "Don't do stupid stuff," Barack Obama, perceiving the US in a relative decline, endorsed the use of "smart power" and proposed "leading from behind" and "Asia-Pacific rebalance," all of which intended to reallocate limited US strategic resources and attach greater importance to the Asia-Pacific rather than Europe.

In addition to strategic value, demographic changes in both the US and Europe and the fading memory of the close relationship, one featuring kinship and brotherhood forged in several wars in history as French President Emmanuel Macronsaid in his speech to the US Congress, will reduce the sense of belonging of the US to Europe's peace and prosperity.

What is more worrying for Europe is that the US might no longer support the current liberal international order based on principles of multilateralism, free trade and openness, which is also the bedrock of transatlantic relations. Europe is also rethinking and adjusting its policies on global issues, but Brussels still believes that the current international system rather than the one Trump envisions is still the best for the continent's interests.

After over a year of flurry with visits and meetings, European countries have failed to find effective ways to persuade Trump to be on the right track. But Europe understands that too much is at stake at this moment since the US is still the most important security, economic and strategic partner and any substantial deterioration of this relationship will result in undermining the current international order.

Therefore, even when Trump's decision to withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal is annoying and frustrating, Europe argues that it cannot burn bridges to the US and should instead reach out more to Washington and make greater efforts to consolidate the basis of US-Europe relations in preparation for the post-Trump era. In this respect, Europeans can only cross their fingers, hoping it is not wishful thinking that transatlantic relations will survive Trump and return to the good old days.