Yasukuni Shrine film still relevant 10 years on

Global Times

1525281772000

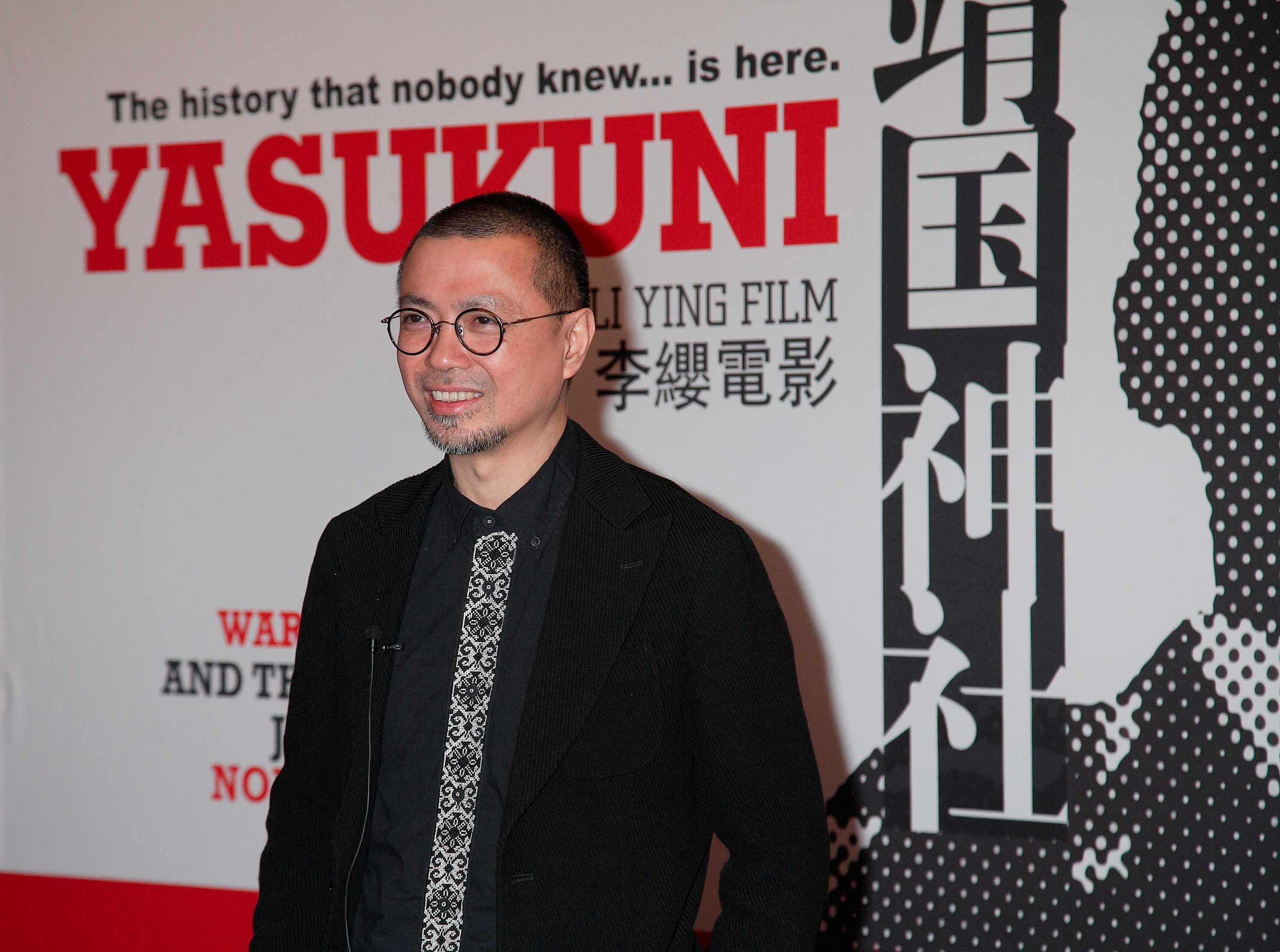

Director Li Ying, who lives in Japan, recalled the release of his documentary 10 years ago.

"One by one the cinemas could not stand the pressure and canceled the premiere of Yasukuni."

During the trip to Japan last week, I attended a meeting in an office of Japan's Niconico, a Japanese video sharing service on the web. One of the topics of the meeting was related to the first documentary on this subject since the end of World War II.

In the office of the website, public relations manager Keizo Yoshikawa told me that on August 15 - Japan's surrender day - 2015, they uploaded the film on their newly started online documentary channel. To ensure company's safety, they said they spent tens of millions of yen on security. Some right-wing organizations had sent them warnings.

The website niconico.com uploads more than 6,000 digital videos every day and has more than 60 million members in Japan, 90 percent of whom are between 20 to 35 years old. The company uses special technology to allow viewers to write their reviews while watching videos.

It took 10 years for Li Ying to finish the film. The production received a subsidy of 7.5 million yen ($68,300) from the Japan Arts Council in fiscal year 2006.

The documentary tells the story of the shrine in Chiyoda, Tokyo, where more than 2 million of Japan's war dead are enshrined. The film explores the meaning of the controversial, symbolic, spiritual, religious site and the complicated subconscious feelings of a nation.

The movie triggered a storm of debate in 2008. Japanese media even created a new term for it: "Yasukuni Fury," as the most significant social and cultural event in the history of post-war Japanese films. The film set box-office records for a Japanese documentary and won the best-documentary award at the Hong Kong International Film Festival.

Yasukuni shows that right-wing forces are still very tenacious. The Japanese view of the war is still quite far from the Chinese people, whose compatriots were profoundly victimized by the war. The shrine issue remains a time bomb in Sino-Japanese relations.

A few days before I arrived in Tokyo, some Japanese congressmen made collective visits to the Yasukuni Shrine.

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe sent a ritual offering before the shrine's spring festival on April 21.

In a bookstore in downtown Fukuoka, I saw two books related to the war on the shelves of bestsellers. One was The Japanese Armed Forces - The Reality of the Pacific War by Yutaka Yoshida. The words "dismal experience" were also printed on the cover. The circulation of this book exceeded 100,000 copies.

The other book, written by Shoji Kokami, was about kamikazes and tells the story of one who repeatedly disobeyed orders and so survived the war.

On other bookshelves, I also saw books that represent the right-wing view and some are notorious for their denial of atrocities.

Without a doubt, the release of Yasukuni in 2007 ripped open a crack and turned an almost taboo issue into a heated topic of controversy.

Niconico.com also uploaded the Chinese movie about the Nanjing Massacre Nanjing! Nanjing! and five episodes of 1937 Nanjing Memory based on the 1997 bestseller The Rape of Nanking by Chinese American author Iris Chang.

The reality is complicated and multifaceted in Japan, one of the most conservative developed countries. In addition to the deliberate distortion of the war in some history textbooks, there are also other kinds of reflections on the war, but those reflections are based on the trajectory of changes in Japanese social thought.

Yes, there are certain distances between Japanese reflections on the war and the Chinese people's hope, but the publication of books, films, cartoons with different viewpoints on war history in recent years, such as The Eternal Zero, a Japanese war drama film and Persona Non Grata: The Chiune Sugihara Story, which tells the stories of Japanese diplomat Chiune Sugihara posted in Lithuania during World War II, illustrates a gradual evolution toward openness in Japanese society.

This kind of openness is related to the public's view of freedom of speech, formed after the war and strengthened by new generations. The Japanese people are more tolerant of different opinions. Many like to hear different views, but not necessarily agree with them. Such opening up created the conditions for them to listen to their neighbor.