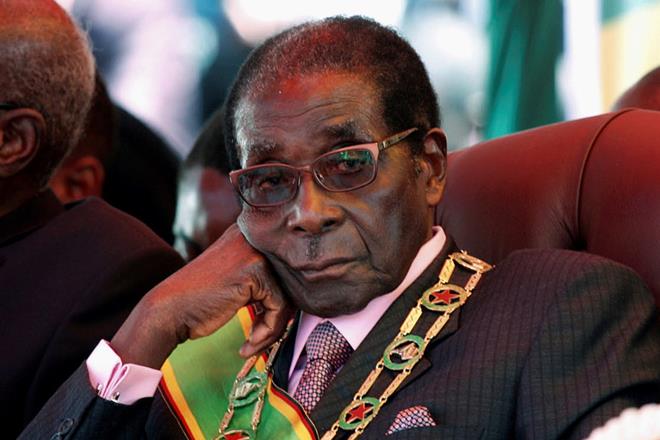

After holding on to power for 37 years, 93-year-old Robert Mugabe resigned as Zimbabwe's president on Tuesday.

Zimbabwe's political turmoil simmered on November 15 after a military takeover, but the Mugabe era ended without any bloodshed. It turned out to be a stroke of luck for an African country, considering the frequency of bloody coups on this continent.

An old man on the verge of senility, Mugabe refused to voluntarily step down. His glory once made him the most powerful man in Zimbabwe, but also placed him in bondage after enjoying the aphrodisiac of power for many years.

The addiction to power finally leads to a personal tragedy for Mugabe, who was imprisoned for fighting for national liberation. Such a tragedy is not just for one person.

The recent turbulence in Zimbabwe not only spells a power struggle, but also reflects on the economic and social contradictions in the country. As a person who had worked in Zimbabwe for three years in the early 1990s, I have witnessed the painstaking efforts it made to deal with social and economic problems.

The Mugabe administration, which took over from white racists, had to tackle difficult problems between white and black people, and handle the clan conflicts among black people as well. The conflicts between white and black people are a complex game that involved political and economic interests.

At the beginning, some 4,500 white landlords owned 60 percent of the fertile land of the country, while about 7 million black people lived with tiny parcels of land or none at all. The issue of land reform had troubled Mugabe from the start. The tricky part was the economic imbalance between white and black people would never be fixed if the problem was not solved. And this was Mugabe's undoing, losing the support of black people who form the majority of the country's population.

Nevertheless if Mugabe touched the fundamental interests of white people, the economic lifeline of the country would be shattered. To make things worse, uncertainties and tactical blunders in policymaking did not win black people's support nor protect the economy from sabotage from white people.

Internal as well as external pressure led to Mugabe's predicament. Just like running water never becomes putrid, governments need people turnover as well. If Mugabe had chosen to retire at the height of his career following the examples of Tanzania's Julius Nyerere and South Africa's Nelson Mandela, and had carried out a system for the long-term interests of the country and of its people, Zimbabwe's political turmoil could have been avoided.

Just like many other countries in the world, Zimbabwe is still exploring its own development paradigm. This effort will not stop even after Mugabe's resignation.

(Compiled by Wang Yi)