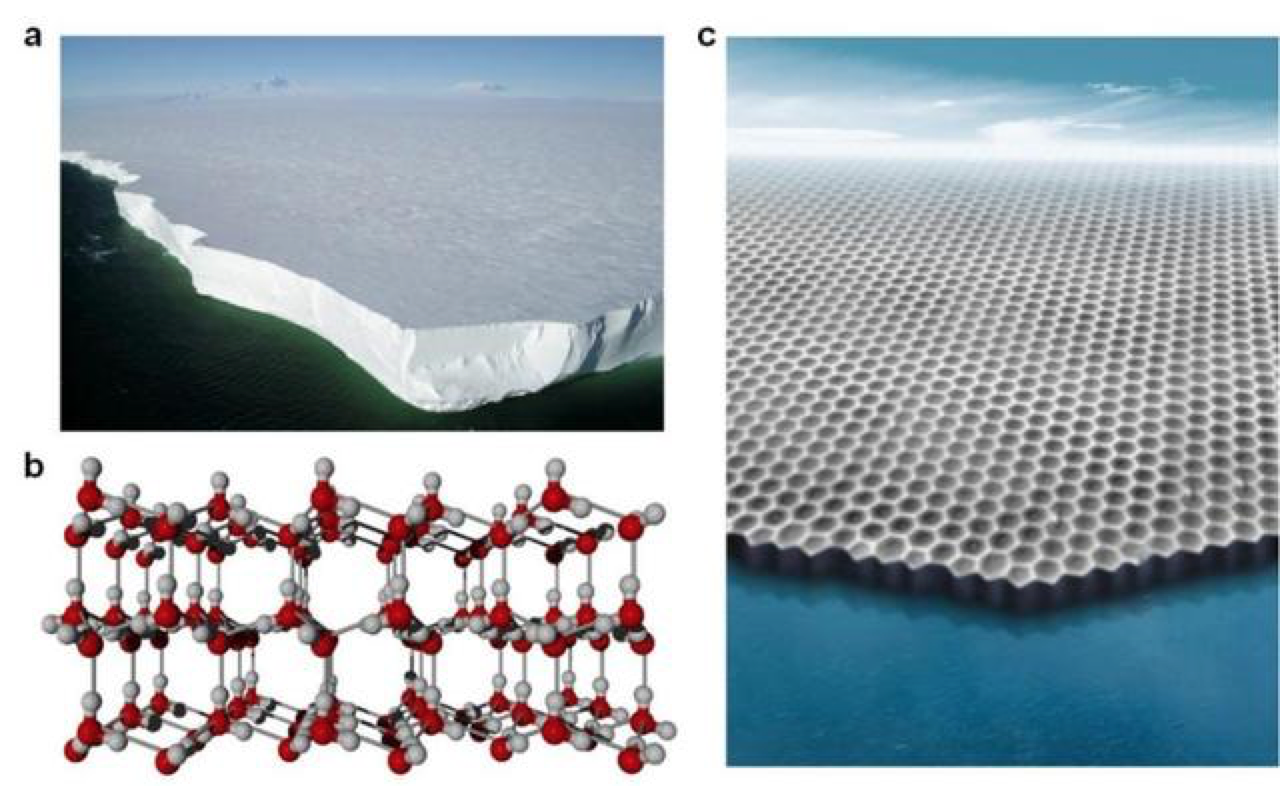

(a) Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica; (b) A molecular model of hexagonal ice; (c) Two-dimensional ice created in this study. (File Photo: Science Daily)

Scientists from Peking University in China and the University of Nebraska Lincoln in the US described the first-ever visualization of the atomic structure of artificially created two-dimensional ice, in a new paper published in the scientific journal Nature on Thursday.

Virtually all naturally occurring ice on Earth is known as hexagonal ice, for its six-sided structure. This is why snowflakes all have six-fold symmetry. Researchers found that one plane or slice of hexagonal ice has a similar structure to two-dimensional ice created in a laboratory, and can terminate in two types of edges— dubbed “zigzag” or “armchair.” Usually this plane of natural ice terminates with a zigzag edge.

The Nature paper, “Atomic imaging of the edge structure and growth of a two-dimensional hexagonal ice,” shows that as ice grows on an artificially-created two dimensional plane, researchers find that its pattern of growth is different. The research, for the first time, showed that the armchair edges can be stabilized and that the ice’s growth follows a novel reaction pathway.

Insights from the findings, which were driven by computer simulations that inspired experimental work, may one day inform the design of materials that make ice removal a simpler and less costly process.

The Peking team used super-powerful atomic force microscopy, which uses a mechanical probe to “feel” the material being studied, translating the feedback into nanoscale-resolution images. Atomic force microscopy is capable of capturing structural information with a minimum of disruption to the material itself, allowing scientists to identify even unstable intermediate structures that arise during the process of ice formation.

"This study opens the door to a serial study of 2D-ice families and changes the people's traditional understanding of two-dimensional ice,” said Guo Wanlin, a researcher at the Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics. “At the same time, it will have a great impact on research and development of materials science, tribology, biology, atmospheric science and planetary science.”

“The two-dimensional work is fundamental to laying the background,” says Joseph Francisco, professor of chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania. “Having the calculations verified by experiments is good, because that allows us to go back to the calculations and take the next bold step toward three dimensions.”

(Compiled by Zhang Bingyu)