File photos: VCG

Researchers at Columbia University and the University of Chicago-affiliated Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) have mapped the full-body muscular activity of an animal while it was moving and behaving, for the first time in the world.

In the study, the researchers watched the patterns of muscle activity in a small aquatic animal called the hydra. Based on prior success in mapping full-body neural activity in a hydra, they pinpointed seven distinct patterns of hydra's muscle activity this time, according to a news release posted on the website of the University of Chicago on Thursday.

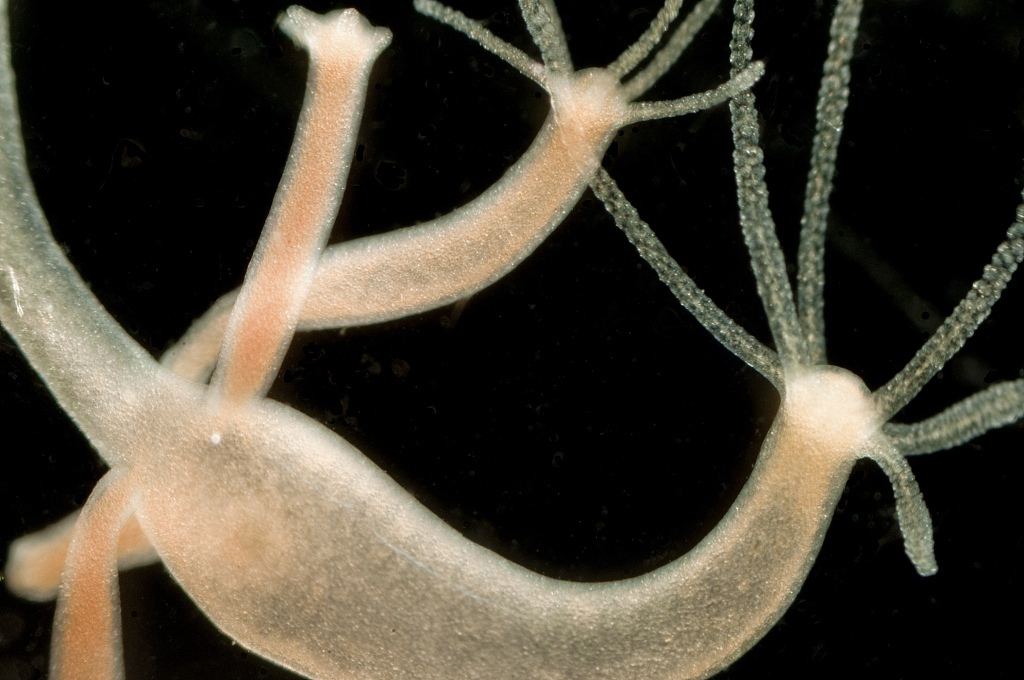

Image of a hydra.

Hydras are freshwater organisms, only a few millimeters in length. Their tubular bodies are comprised of two layers of muscle, each composed of a different cell type and separated by two nerve nets.

Although the two tissues do sometimes work independently, the researchers found that in certain instances both layers of muscle are active, possibly allowing the animal to expel the influx of water that is constantly flowing into its cells.

Each individual cell also appeared to serve more than one function, and participate in more than one activation pattern. In fact, the nerve nets appear to play a relatively limited role in the movement. Neurons may initially trigger the activity, but the patterns of propagation are organized by the muscle cells themselves working in unison.

Hydras under the microscope.

"The patterns of activation we identified were not implemented by specific, dedicated cells, but instead depended on the properties of the muscle tissue as a whole, and the interconnections between cells," said first author John Szymanski, a former MBL Whitman Center investigator.

"We are now poised to do the hard job, which is to link the activity of neurons, muscle, and behavior and decipher the neural code to explain completely how the nervous system creates behavior, at least in one animal," said senior author Rafael Yuste of Columbia University.

The study has brought researchers a step closer to "breaking the neural code" and understanding the relationship between a stimulus and its neural response.

The study has been published in Current Biology.