(File Photo: CGTN)

Brandon Jewett is a commercial pilot who, in his spare time, flies his Douglas DC-3, a propeller-driven plane that was used to transport troops during World War II.

"If you were driving your car versus driving a motorhome, this is like driving a motorhome," Jewett said during a recent brief tour of the aircraft. The cockpit is appropriately retro.

"So this is our main instrument panel here," he said. "But here's our whiskey compass, front and center if you will."

Whiskey compass is one of the originally required basic instruments that every single airplane must have. (Photo: CGTN)

The whiskey compass was named for the alcohol that once lubricated these devices. Even today, in this high-tech and GPS-driven age, the compass remains an indispensable tool for pilots.

"And to this day, it is one of the originally required basic instruments that every single airplane must have," Jewett said.

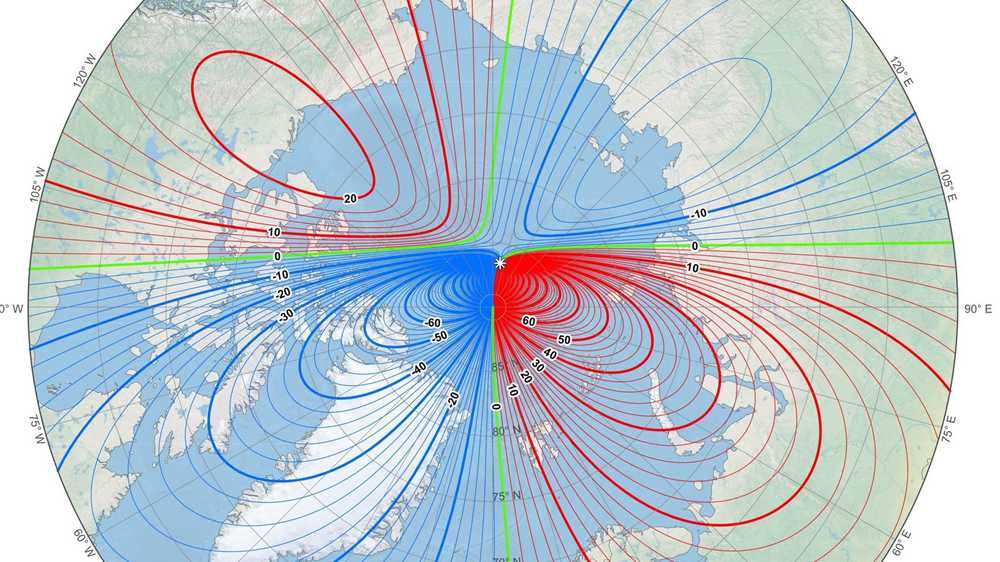

Most compasses use Earth's magnetic field to tell us which way is north. The problem is the magnetic North Pole has always had a hard time staying in one place. In fact, it was moving at the rate of 10 to 15 kilometers per year from the Canadian Arctic towards Siberia. Then in the 1990s, it sped up to 55 kilometers per year.

"I find it spectacular that the speed increased that much in such a short period of time," said Arnaud Chulliat, a research scientist with the University of Colorado Boulder. He said the move was likely caused by the flow of liquid iron deep inside the Earth's core.

"These motions generate most of the Earth's magnetic field, and they're also responsible for variability of this magnetic field," Chulliat said.

Gradually, the Siberian sprint, as it's been called, has made the navigational maps used by airlines and ships out of date.

"Where it becomes critical for a pilot is if you were trying to navigate with an old chart," Jewett said. "You'd have inaccurate information."

In February, scientists released an emergent update to the World Magnetic Model that aids global navigation. And over time, airports have had to rename runways that were named for their magnetic heading.

"They've all had to renumber the runways, re-index them, because it's changed that much," Jewett said.

The polar drift has even led to speculation that a weakening magnetic field might lead the North and South Magnetic Poles to flip spots. That last happened 780,000 years ago. No signs of that just yet.

"I don't think there's any reason for particular concern," Chulliat said.

Jewett has updated his compass. It's an instrument pilots can't do without.

"There's endless aviation stories of how the compasses saved their life," Jewett said. "You know, helped them find where they were going."

As for where the North Pole is going? It's anyone's guess.