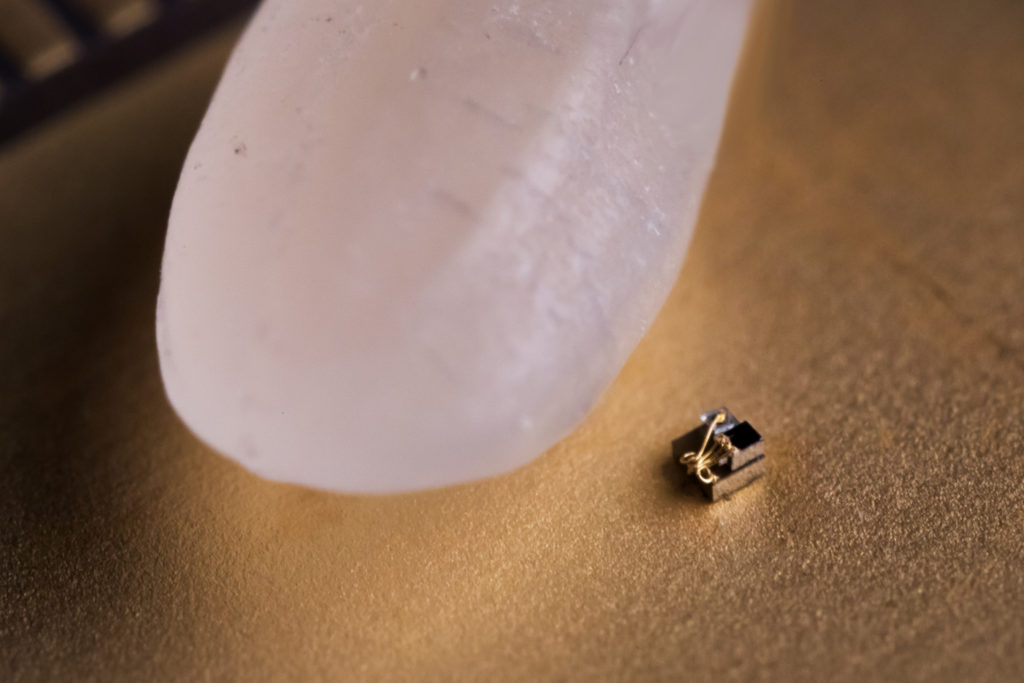

(Photo: University of Michigan)

Researchers from University of Michigan have outdone IBM in creating the world’s smallest computer measuring just 0.3mm— completely dwarfed by a grain of rice, the school’s official website announced on Thursday.

The invention came after IBM’s announcement in March, claiming its newly developed 1mm x 1mm computer to be the smallest one in the world. But for Michigan’s team, home to the previous champion of tiny computing, its creation is about more than size.

"We are about 10x smaller so we can fit in smaller spaces," David Blaauw, a professor co-leading the project, said in an email statement. "Also, the IBM computer can't sense its environment —it can send a code identifying itself but it does not sense its physical surroundings."

Unlike traditional desktop computers that always retain their program and data there even if unplugged or having power back, these new micro devices lose all prior programing and data as soon as they lose power.

"We are not sure if they should be called computers or not. It's more of a matter of opinion whether they have the minimum functionality required," said Blaauw.

In addition to the RAM and photovoltaics, the new computing devices have processors and wireless transmitters and receivers. Because they are too small to have conventional radio antennae, they receive and transmit data with visible light. A base station provides light for power and programming, and it receives the data.

However, the light from the base station—and from the device’s own transmission LED—can induce currents in its tiny circuits. So new ways of approaching circuit design that would be equally low power but could also tolerate light were invented to ensure the tiny computer ran at very low power when the system packaging had to be transparent.

Besides, designed as a precision temperature sensor, the new device converts temperatures into time intervals, defined with electronic pulses. The intervals are measured on-chip against a steady time interval sent by the base station and then converted into a temperature.

As a result, the computer can report temperatures in minuscule regions—such as a cluster of cells—with an error of about 0.1 degrees Celsius.

The system is very flexible and could be reimagined for a variety of purposes, but the team chose precision temperature measurements because of a need in oncology.

"Since the temperature sensor is small and biocompatible, we can implant it into a mouse and cancer cells grow around it," said Gary Luker, a UM professor of radiology and biomedical engineering.

"We are using this temperature sensor to investigate variations in temperature within a tumor versus normal tissue and if we can use changes in temperature to determine success or failure of therapy."

The researchers also look forward to what purposes others will find for their latest microcomputing device, named the Michigan Micro Mote.

The study was presented at the 2018 Symposia on VLSI Technology and Circuits.

(With inputs from Xinhua)