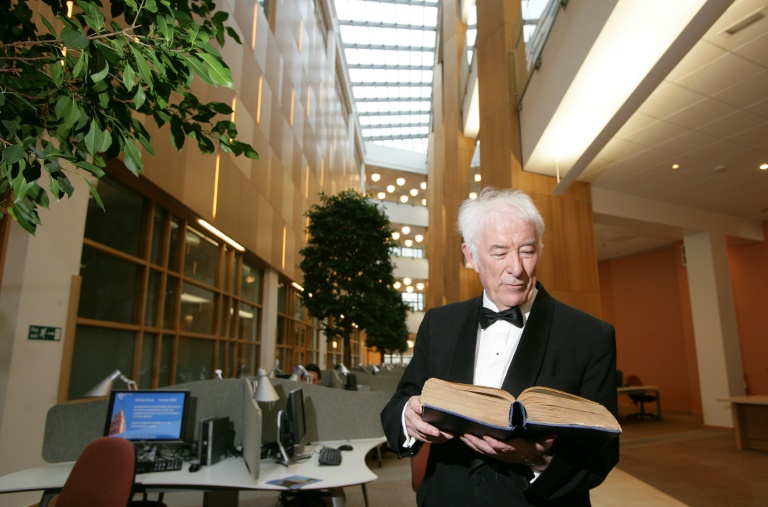

In the opening weeks of the lockdown, Nobel prize-winning poet Seamus Heaney's promise of reward for endurance struck a chord across Ireland. (Photo: AFP)

Ireland has sought solace in its poetic tradition to overcome the coronavirus crisis and provide poignant words of hope to tackle grief and the hardship of lockdown.

Verse is ingrained in public health messaging, doorstep banners quote hopeful lines, and the state broadcaster rounded out news of one death toll with a lyric assuring: "Everything is going to be alright."

"Poetry is just imbued in Irish society very very strongly and we turn to it at these kind of times," poet Catherine Ann Cullen told AFP.

Ireland has suffered a relatively modest 1,571 deaths from COVID-19 according to latest department of health figures.

But it still faces a long road out of lockdown which began on March 28.

A government scheme to reopen the nation will reach its final steps in August.

In the opening weeks of the lockdown, Nobel prize-winning poet Seamus Heaney's promise of reward for endurance struck a chord across Ireland.

"If we winter this one out, we can summer anywhere," was a message which appeared on handmade banners, scrawled on Dublin walls and multiplied on social media.

Taken from an interview with Heaney in 1972, it referred to "The Troubles" over British rule of Northern Ireland which by its end in the late-1990s killed 3,500.

In the current health crisis, the quote found new resonance.

"It's like a little meditation, it's like a little mantra," said Cullen, Poetry Ireland's current poet-in-residence.

"They give us kind of hope," she said of such lines.

One month into the lockdown, the Irish poet Eavan Boland died.

That left fans to reflect on a body of work which also draws on Ireland's difficult history, while offering solace in the present.

Her 1994 poem "This Moment" was shared on social media as a memorial, sparking hope for those in isolation with its depiction of a neighbourhood at dusk.

"Things are getting ready/to happen/out of sight," it reads.

In April, Poetry Ireland partnered with charity Alone which supports solitary older people, many currently "cocooning" from the coronavirus.

The elderly in lockdown were invited to request poetry recitals by phone from writers.

Testimony from the event reveals the comfort taken by in the exchanges, where Boland's work was a popular choice.

"My aunt got dressed up and made up for the occasion and was completely delighted," one family member said in feedback to the organisation.

In Ireland, memorised snippets of such poems can function like secular Bible verses -- to be memorised and presented for their enduring wisdom and comfort.

"For my mum it was also a complete thrill. Her reader read a fun one and a deeper one which really hits on how my mum is in the world," the family member added.

In Ireland, poetry and politics have long been intertwined.

The 1916 uprising which began the path to independence from Britain is often called "The Poet's Revolution" after the number of artists involved.

Now, poetry has become embedded in crisis officialdom -- in political speeches and public health messaging, weighing them with a sense of gravitas.

Prime Minister Leo Varadkar has replaced his usual understated rhetoric with poetic stylings -- borrowing heavily from the verse of Heaney.

"These words have provided inspiration to many Irish people as we deal with this emergency," he said in an April address to the nation.

"They remind us that we are in this together, we can get through it, and better days will come."

Meanwhile, the work of President Michael D. Higgins -- a published poet -- has been embedded in adverts by Ireland's health service imploring the public to "hold firm".

"Historically we're a very poetic society," explained Cullen.

"People turn to poetry in times of crisis."