View of the Mississippi Delta. (Photos: Zhang Mengxu/People's Daily)

Washington (People's Daily) -- Which state is the poorest in the United States? The answer is Mississippi.

"Poverty seems to be a label that Mississippi can't erase," Corey Wiggins, executive director of the Mississippi state conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), said in an interview with People’s Daily.

In 2017, the national poverty rate in the US was 13.7 percent, but in Mississippi it was 20.8 percent, the highest in the country. The second worst was Louisiana at 20.6 percent.

"This is the 'Southern issue' in the US," said Robert Gilpin, a professor of history at Tulane University.

Lower ninth in New Orleans is still lifeless.

The Lower Ninth District of New Orleans was once the most populated African-American community in Louisiana with more than 98.1 percent of houses owned by African-Americans. In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina smashed New Orleans and almost all homes in this area were destroyed.

Today, the community still seems desolate and lifeless.

"Residents who have lost their homes live in cheap apartments provided by the government, and some live in relatives' homes,” Laura Paul, head of a local charity organization, told People’s Daily. “In short, everyone finds their way out."

Paul runs a charity that aims to help residents who lost their homes because of Katrina. She brought People’s Daily’s reporters to the only home reconstruction project in the region.

“After passing the qualification review, the homeowner waited for nearly three years before finally seeing the project start.”

Paul said that her organization’s funds are mainly from donations. Since its establishment in 2007, they have completed 87 reconstruction projects and partial repairs of more than 300 houses. “As time goes by, people are paying less and less attention to this area, and it is becoming more and more difficult to raise funds,” she said.

When asked if it’s a common problem in the reconstruction of New Orleans, Paul said that after the hurricane, 80 percent of New Orleans was flooded, but the situation in the lower ninth district was extremely special, mainly because it was an African-American dominated community.

“In the post-disaster reconstruction, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) assistance is not equitably distributed among communities. The compensation for rebuilding houses is based on the market price before the house was destroyed,”Paul told People’s Daily.

Paul said the market price of property in the lower ninth is only one-quarter of the city's average price, so compensation received by residents is simply not enough to repair a home.

Tarbeville chats with neighbors outside his house.

Raymond Huang is a 60-year-old second-generation American Chinese living in Greenville, Mississippi. He has a lot of local friends. 61-year-old African-born Tarbeville is one. His home is in a very common African-American community.

It is a bungalow of less than 80 square meters. Like other houses on the street, the exterior wall has peeled off paint and wiring is exposed. There are chairs in the small front yard where neighbors sit and chat. Tarbeville divorced his wife more than 10 years ago and their three children live with her. He and his brother Bill pay $300 a month in rent.

Tarbeville served in the marines for 17 years and moved to Texas, South Korea, and Germany. After retiring, he returned to work as a turner at a factory in Greenville. “The temperature in the workshop was very high, effecting my health,” he said.

Tarbeville left the factory at the age of 50 and has since worked odd jobs. “We need more jobs. But over the years, I have only seen disappointment.” Now, he receives $750 a month in unemployment benefits from the government.

The walls of the Greenville History Museum are full of photos of school graduates, including Tarbeville and Bill.

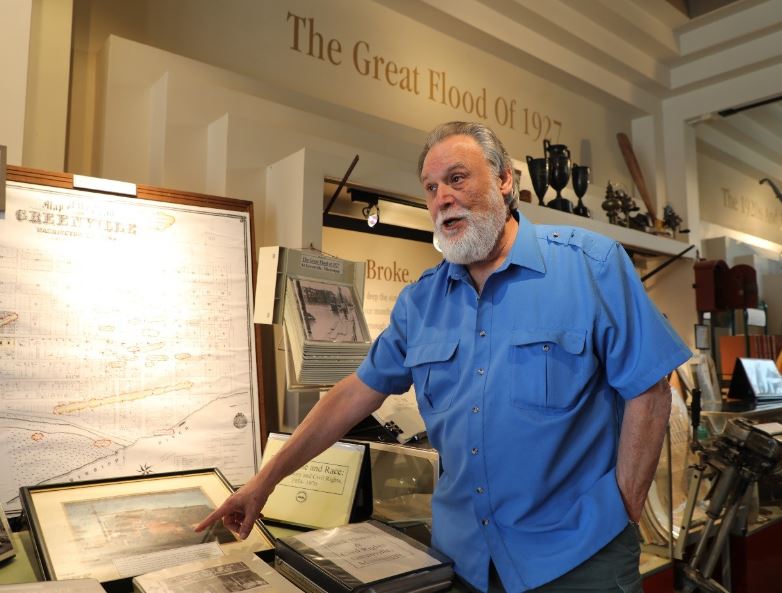

Benjamin Nielken in the Greenville History Museum.

"I am most worried that the city will keep shrinking, because this small place doesn’t get any interest from politicians," said museum director Benjamin Nielken.

"I always listen to people excited to say that another big company is coming to invest here. In the end it is just another rumor. Year after year, it has not changed."

The Mississippi Delta covers 19 counties with a population of approximately 440,000, of which 60 percent are of African descent. In 1990, Greenville had 45,000 inhabitants, and today there are only 31,000. Because of the lack of development opportunities, young people have to go far away.

The rise and fall of the local Chinese community is also a microcosm of the region’s shrinking. After the American Civil War, the first Chinese came to the plantations of the Mississippi Delta to work as laborers. According to Huang, there were more than 50 Chinese grocery stores in Greenville, but only one is left.

"There is no chance, no prospects." He has three children, one in Los Angeles and two in Houston.

At the Greenville City Hall, People’s Daily reporters met with the young mayor Eric Simmons. In his view, the Mississippi Delta did not properly deal with two shocks. One was large layoffs caused by agricultural mechanization, and the other was the hollowing out of manufacturing.

For decades, it has become a corner forgotten by American politicians. The only jobs are limited to hotels, restaurants, supermarkets and other service industries. The wages are low. In 2017, the annual income of local families was less than half of the national average.

"I want Greenville to see hope, but it's too difficult." Simmons admitted that the primary problem he faced is education.

80 percent of Greenville’s residents are African-Americans. Children from better family economics have gone to private schools, and African-American students in public schools account for 99 percent of the total, and almost all come from families below the poverty line. Simmons said he tried to bring positive changes to public schools, such as computer programming, plumbing repairs, welding techniques, etc., but he could not find corresponding internships.

Another big problem is the dilapidated infrastructure. Because of the high unemployment rate and high poverty rate, the government's annual fiscal revenue is extremely limited. Without the money to improve the infrastructure, it will not attract investment. Simmons said that within the last two years, a company that wanted to set up a factory here and create 1,000 jobs learned that the local sewage treatment capacity was weak, so switched to Atlanta.

“This is a vicious circle. Without good infrastructure and no funds to improve it, economic development will be limited,” he said.

More than 50 years ago, poverty in the Mississippi Delta drew national attention. In 1967, the US Senate sent a team to the area to investigate. A baby crawling on the floor picked up dirty food and put it in his mouth. This surprised then Senator Robert Kennedy and he vowed to make life better in the poorest areas of the United States.

More than 50 years later poverty is still there. According to the NAACP’s Wiggins, more than half of Mississippi's regions are long-term poor counties, and generations of people living in extreme poverty are commonplace.

“Examining the history of the American South, the earliest plantation economy here was based on the exploitation of African-Americans. Today it is still a low-wage economy, schools do not have enough resources, and systematic and institutional factors are keeping us in poverty."

As Wiggins said, governance of poverty is a systematic project, which needs education, investment, concept renewal, blueprint planning, etc. But in reality, it is difficult to have these elements in a region with a relatively large African-American population such as Mississippi.

“Although slavery has long since been abolished, this does not mean that people begin to treat each other equally. Prejudice and discrimination still exist in people’s minds and lead to intergenerational cycles of poverty in this region,” said Robert Gilpin, who has been teaching for many years.

He often plays a video to students about a white school where an African-American girl came and a white parent immediately took their child away.

Racial inequality is a gap that straddles people. Joseph Stiglitz, a professor of economics at Columbia University, wrote in his article, "Over the past 50 years, the United States has remained a highly divided country, and economic opportunities seem to be decreasing for Africans."

Gilpin said, "President Thomas Jefferson once believed that the relationship between African-American slaves and whites would take several generations to work itself out, but I think he underestimated the seriousness of the problem."

The unfair design of the political structure further strengthens economic inequality. African-Americans traditionally support the Democrat Party, but Mississippi generally votes Republican.

According to Wiggins, the result of the bipartisan dispute is that the desire of people of African descent to improve their communities, improve the level of education and medical care, and narrow the gap between the rich and the poor, has never been reflected in policy.

“Enterprises decide where to invest, not only to study the local tax system, but also to measure the labor situation, education level, health status, etc. Without these advantages, it is difficult to attract investment,” he said.

“If you do screening in the local male workforce and remove criminal records and drug addicts, there are very few qualified candidates. In that case, who will invest?”

In Gilpin's view, the current US political split is increasingly polarized. Many policy recommendations to change poverty in the southern states were stifled during the discussion phase.

The “Southern issue” that has lasted for many years still has not seen a sliver of light.