The Moon is steadily shrinking, causing wrinkling on its surface and quakes, according to an analysis of imagery captured by NASA"s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) published on Monday.

A survey of more than 12,000 images revealed that lunar basin Mare Frigoris near the Moon"s north pole – one of many vast basins long assumed to be dead sites from a geological point of view – has been cracking and shifting.

Unlike the Earth, the Moon does not have tectonic plates. Instead, its tectonic activity occurs as it slowly loses heat from when it was formed 4.5 billion years ago.

This, in turn, causes its surface to wrinkle, similar to a grape that shrivels into a raisin.

Since the Moon"s crust is brittle, these forces cause its surface to break as the interior shrinks, resulting in so-called thrust faults, where one section of the crust is pushed up over an adjacent section.

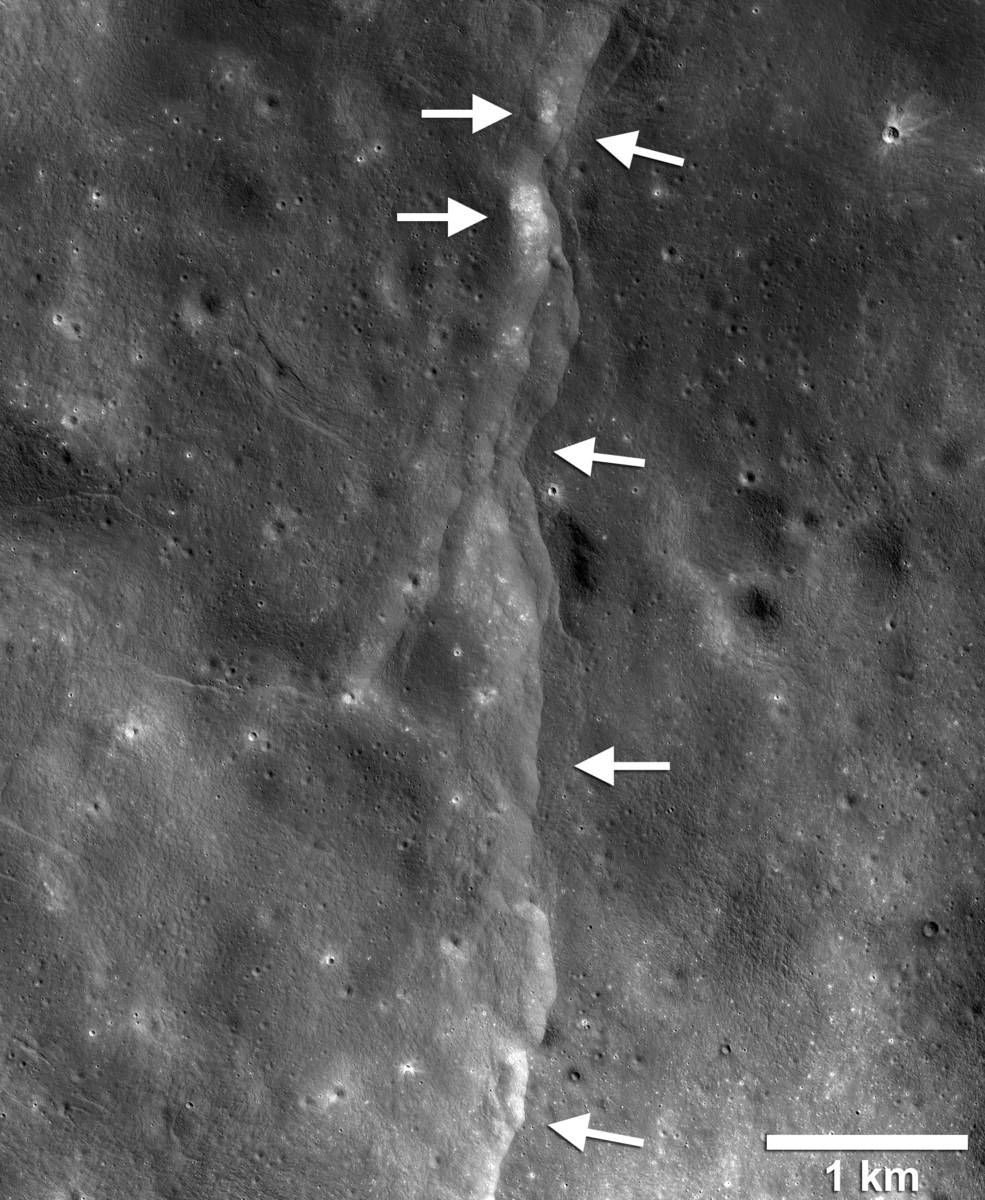

This prominent lunar lobate thrust fault scarp is one of the thousands discovered in Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera images. The fault scarp or cliff is like a stair-step in the lunar landscape (left-pointing white arrows) formed when the near-surface crust is pushed together, breaks, and is thrust upward along a fault as the Moon contracts. Boulder fields, patches of relatively high bright soil or regolith, are found on the scarp face and back scarp terrain (high side of the scarp, right-pointing arrows). /NASA Photo

This prominent lunar lobate thrust fault scarp is one of the thousands discovered in Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera images. The fault scarp or cliff is like a stair-step in the lunar landscape (left-pointing white arrows) formed when the near-surface crust is pushed together, breaks, and is thrust upward along a fault as the Moon contracts. Boulder fields, patches of relatively high bright soil or regolith, are found on the scarp face and back scarp terrain (high side of the scarp, right-pointing arrows). /NASA Photo

As a result, the Moon has become about 50m "skinnier" over the past several hundred million years.

The Apollo astronauts first began measuring seismic activity on the Moon in the 1960s and 1970s, finding the vast majority occurred deep in the body"s interior while a smaller number were on its surface.

The analysis was published in Nature Geoscience and examined the shallow moonquakes recorded by the Apollo missions, establishing links between them and very young surface features.

"It"s quite likely that the faults are still active today," said Dr. Nicholas Schmerr, an assistant professor of geology at the University of Maryland who co-authored the study.

"You don"t often get to see active tectonics anywhere but Earth, so it"s very exciting to think these faults may still be producing moonquakes."

(Top image: A view of the Taurus-Littrow valley taken by NASA"s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft. /NASA Photo)