Despite the economic effects of the pandemic, EU housing prices went up by 5.2 percent in the second and third quarter of 2020. (Photos: CFP, VCG)

The state of the housing market tends to be a good indicator of what's on the economic horizon: a sharp drop often follows a crisis, or is a signal of an impending one. But as the COVID-19 pandemic inflicts the biggest economic downturn since World War II, European house prices, far from dipping, have continued to rise.

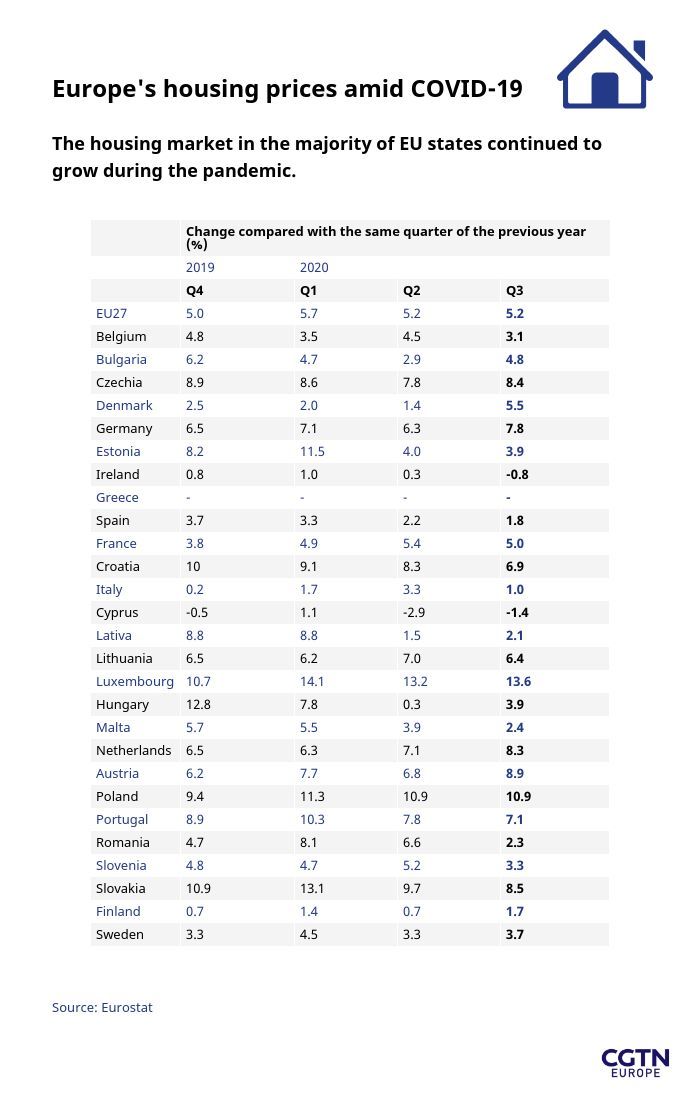

In the EU, property valuations were 5.2 percent higher in the second and third quarter of 2020 compared with the previous year. In the UK, which experiencing the worst economic slump on the continent, house price growth hit a four-year high.

So why have they kept on growing? Are the figures really representative? And does never-ending inflation in the housing market spell trouble for the future?

Protecting the market

"I made this prediction that house prices would fall back in April because of the expectation of the effects of COVID-19 on personal incomes and the economy," says Paul Cheshire, an emeritus professor of economic geography at the London School of Economics (LSE).

Indeed, many European economists – looking to previous recessions as an example – quite reasonably predicted a drop. But in the first nine months of 2020, the annual growth rate for EU house prices stayed well above 5 percent, levels that had not been recorded since 2007.

Among the top tier countries for price growth, Poland hit a 10.9 percent increase in the third quarter, with Austria at 8.9 and Germany reaching 7.8. Building society Nationwide reported British prices ending the year at 5.3 percent above pre-lockdown figures. Essentially, the European housing market had shown a surprising resilience to a crisis that had savaged many other sectors.

Reassessing his prediction nine months later, Cheshire says the key reason the drop never came, at least in the short term, is that nearly "all European countries... are supporting their economies and particularly supporting individual households, and especially house ownership."

On a wider level, this includes furlough programs, measures to protect small businesses like working capital loans, and the continent-wide push to keep the service economy running through remote working. Many workers have been able to keep on earning, which has avoided the sort of mass of forced sales seen in previous recessions.

State intervention to protect the market also became the norm across Europe. Many countries imposed a temporary halt on evictions for renters in arrears. In the UK, the Conservatives brought in a so-called 'stamp duty holiday' so that people buying a home didn't have to pay any state tax on the purchase.

"There's also been huge pressure brought to bear on the mortgage lenders not to foreclose," says Cheshire. Alongside Britain, EU countries like Germany and France have given mortgage holidays for those who can't keep up payments due to the pandemic, meaning they haven't yet been forced to sell.

According to Christian Hilber, a professor of economic geography at LSE, "in some sense, a crash in the housing market has been prevented, at least in the short term, by policymakers."

Getting out of the city

The novel approach to housing hasn't been exclusive to lawmakers – the pandemic has also caused a dramatic shift in the attitude of the European public towards home ownership.

Citing the remote working revolution, the constraints on city life, and economic hardship inflicted by the coronavirus, Christine Whitehead, an emeritus professor of housing economics at LSE, suggests this may be one of the reasons why the sector has continued to grow.

"There's an awful lot of people rethinking all sorts of things which one doesn't expect," says Whitehead. "People have started to look for accommodation that has more outside space, more inside space, out of central and major cities."

More than 40 percent of people living in major European cities have thought about moving away due to the pandemic, a study from British engineering firm Arup shows.

According to a December survey from the Dutch financial services company ING, more and more Europeans – some 45 percent of those polled – said they were thinking of moving home, with just under half hoping to do so within the next 24 months.

Many of those wanting to move – especially younger people, the report says –aim to trade in expensive smaller flats for cheaper living spaces, especially now it has become easier to work from home.

Among Whitehead's immediate neighbors in London, she knows of at least three people who are now thinking of buying outside of the city, their life-changing intentions informed both by the current restraints on urban life and government encouragement, like the UK's stamp duty holiday.

Cheshire agrees the housing price surge has likely "been strongly reinforced by the pandemic making space essentially more valuable – both inside houses to work from home, and green space around houses."

Living through a pandemic – and its lockdowns – has made city living unattractive to many.

Coming downturn

Another big influence on the market, according to the ING survey, is the almost unprecedented increase among those who expect house prices to fall in the near future.

Whitehead says current growth could be partly explained by the idea that now is the right time to move. "People think it's probably no worse than any other time," she says.

"If they don't do it now, they're probably not going to be able to move for a couple of years because nothing's going to be moving," she adds, suggesting a delayed impact of the economic crisis when measures to protect people's livelihoods are stripped back.

However, she stresses that the majority of the people currently looking to buy – and the people that have therefore pushed up housing prices – are the ones who have been relatively unscathed by the pandemic.

"We're talking about existing owners making a change to their financial portfolio," she say. "That's the upper end of the market." And this is perhaps the key reason why housing prices – perhaps deceptively – have continued to grow on paper.

Growing problem

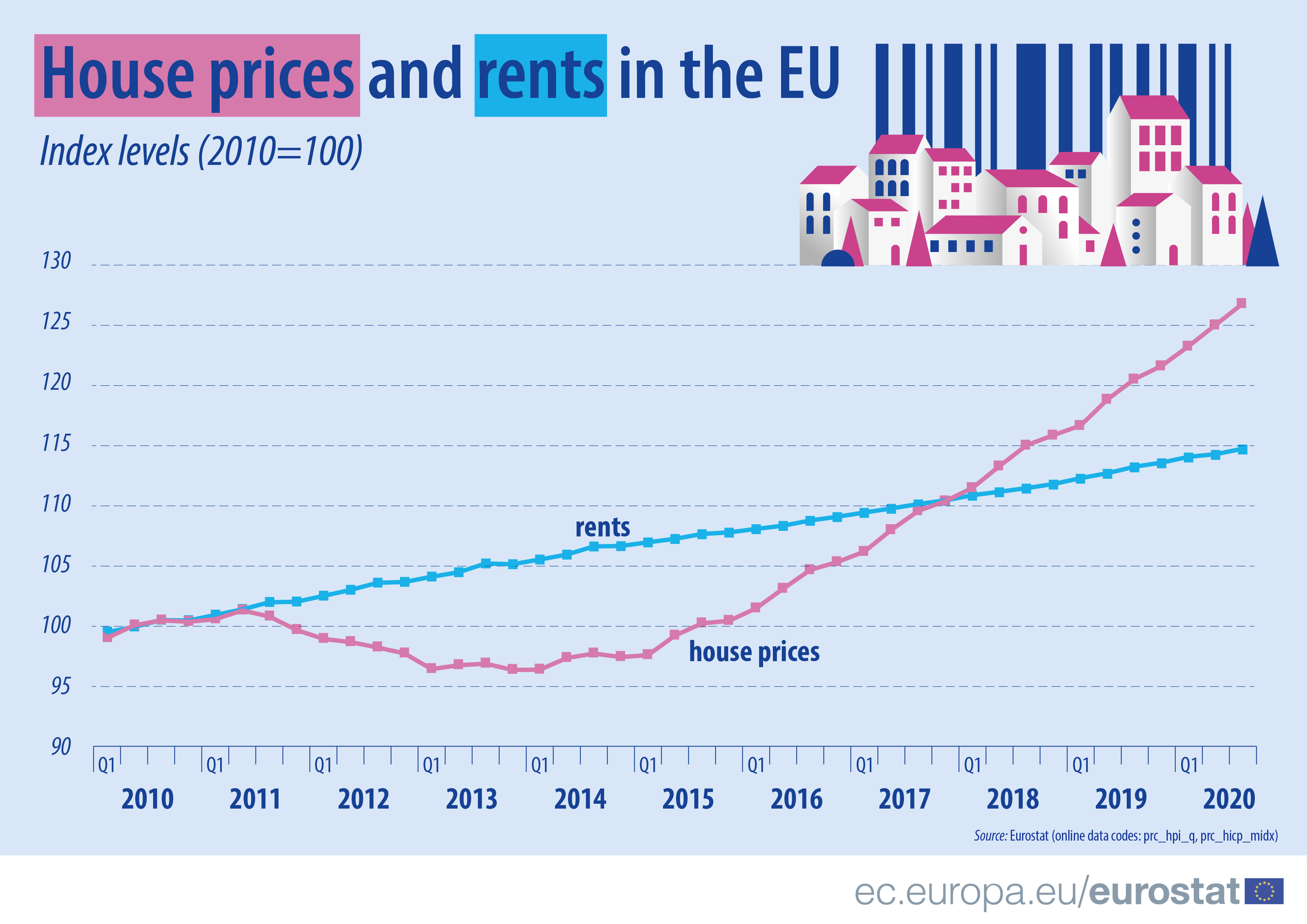

To some extent the current boom is simply an extension of what's been happening in the European market since the 1970s. An increase in urban populations, growing wealth inequality in real terms, and the demand for housing exceeding supply – in part because of tight building restrictions – have all helped to keep most European house prices growing, particularly over the last three decades.

"If you've got a very inelastic supply of housing," says Cheshire, "what happens is, if incomes go up – and demand is chiefly driven by people's incomes – prices go up."

This is particularly acute in the UK, he says, but also a tendency all over Europe, as coronavirus restrictions continue to widen the wealth gap.

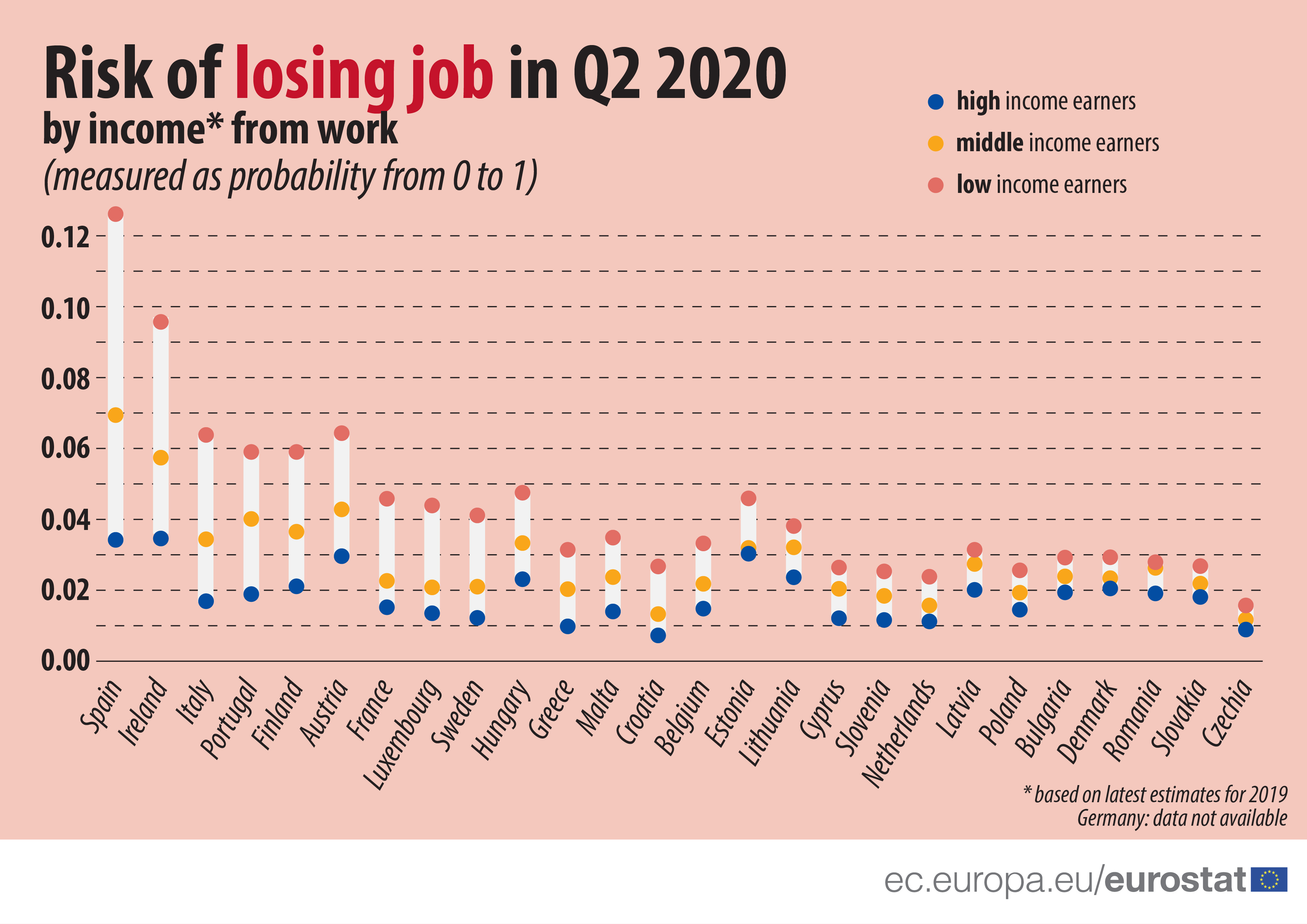

The IMF estimates that income inequality was more acute in 2020 than in any other previous economic crisis, with savings booming for higher earners – the majority of whom have been able to continue working from their homes, unlike many of their low-income counterparts.

"The richest 10 percent in Britain – and not just in Britain, across Europe – have got richer relative to the poorest 10 percent or the poorest 20 percent," says Cheshire.

"That's enabled them to increase their consumption of space, but against a very inelastic demand for housing, so that pushes up the price of bigger houses, with more space and bigger gardens." However, the economist says that doesn't necessarily mean more people are buying.

Research shows the boom in London's housing market was powered by the wealthy buying detached houses in the center of the British capital.

Juking the stats

Research by Cheshire and Hilber on London's housing market during the pandemic shows the housing price hike has been powered almost entirely by the wealthy buying large, detached houses in the center of the British capital.

"Everybody assumes it's in the suburban areas," says Hilber, but apparently there was no evidence of a price increase there. He says the boom "was entirely driven by central London."

During Europe's successive lockdowns in 2020 the number of housing transactions dropped dramatically. At some moments in the UK, rates were down by more than 80 percent.

"All these statistics that you see are based on a very small sample," says Hilber, citing city-center sales of luxury housing, unrepresentative of the wider market.

In an economic downturn people are less likely to sell their houses to avoid any losses, even if there's a threat the value of their house may go down.

Another reason why the numbers may remain deceptively high, he adds, is loss aversion – the concept in economics psychology that people have a tendency to want to avoid losses more than they would desire acquiring equivalent gains.

Hilber notes that during an economic downturn, people are less likely to sell their houses to avoid any losses, even if there's a threat the value of their house may go down or they may be forced to sell. "Fewer houses are sold and the market becomes illiquid," he says.

Particularly at the start of this cycle, that means prices don't necessarily represent actual value. "You're not going to see a drop in prices at first because nobody is selling," he says.

He stresses that London is not necessarily representative of the UK, or Europe for that matter – but that according to European Central Bank metrics, much of the continent was already overvaluing prices in mid-2020.

"Essentially, I don't believe that house prices have gone up as much as what you see in some of the headlines," says Hilber, adding that we may soon see a reckoning.

The future of housing prices

The real danger, according to the economists, is that when government support schemes end – when incomes are no longer protected and firms are forced to fire more workers – the true economic toll of the pandemic will hit the housing market hard.

"That could lead to a fall in prices and possibly a substantial fall," he says. "I just think it hasn't happened yet."

There's also the concern that if banks start to believe house prices will dip, then they could rein in mortgage lending, especially if the incomes to pay them off disappear because of mass job losses.

Even so, Hilber says any dip is likely to be short-lived: "In the very long run, prices will increase again and that's because [housing] supply is extremely constrained."

Unless there is "a massive reform" of the planning system and significantly more houses are built, he believes prices will continue to go up. As he puts it, that's "bad news for young people – prices will increase again because of these institutional problems."

Should we worry about growth?

Rising housing prices have long been regarded by many as a good thing, the idea being that home ownership gives long-term returns on people's investment. However, many economists fear the effects have become divisive.

"I've always been worried about the fact that house prices are rising because I think they're becoming unaffordable," says Cheshire. "It's bad for welfare, for people's well-being, and it's also diverting resources into investments which basically don't yield anything."

He says in countries like Switzerland, money is more likely to be invested in new economic activities, bringing about healthier investment in the real economy – whereas Britain's spare cash nearly all goes on housing, "because it looks like such a good investment relative to the alternatives."

Not only does a highly speculative or widely fluctuating housing market tend to have a negative impact on the wider economy, but also Cheshire says the concentration of money in housing has seen "a huge redistribution away from younger people to older people, away from people whose parents didn't buy houses to people whose parents did back in the 1950s or in the 1970s."

A highly speculative or widely fluctuating housing market can often have a negative impact on the wider economy, according to experts.

He estimates the capital gains he's earned on his housing in the UK have greatly exceeded all the salary he's ever been paid as a senior academic: "It's an insane travesty of how incentives should operate."

As for how to proceed as someone looking to buy a house amid such uncertainty, Whitehead has some advice: "Don't buy unless you're prepared to live in it for at least five years – and expect that sometimes prices will go down."

She adds that with such inequality and slim economic pickings for many young Europeans, the market probably "isn't quite as stable as perhaps we think it is."

For Whitehead, the future is uncertain, and potentially very worrying.

"I don't think people actually have any understanding – nor do I – of what the economy is going to look like in the middle of 2021," she says, "but I don't think we're all going to be full of enthusiasm."